Sinoatrial node

| Sinoatrial node | |

|---|---|

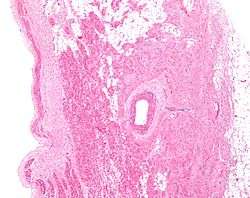

Low magnification micrograph of a sinoatrial node (center-right on image) and its surrounding tissue. The SA node surrounds the (sinuatrial) nodal artery (on lumen in the image), a branch of the right coronary artery, abuts cardiac myocytes (of the right atrium) on its deep aspect (left of image) and adipose tissue on its superficial (epicardial) aspect (right of image). H&E stain. | |

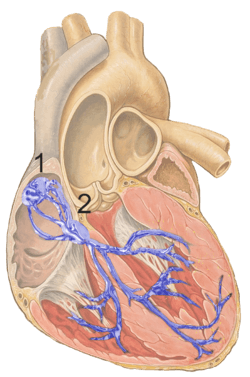

Isolated heart conduction system, showing SA node | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Sinuatrial nodal artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nodus sinuatrialis |

| MeSH | A07.541.409.819 |

| TA | A12.1.06.003 |

| FMA | 9477 |

The sinoatrial node (often abbreviated SAN; also commonly called the sinus node and less commonly the sinuatrial node) is the normal natural pacemaker of the heart and is responsible for the initiation of the cardiac cycle (heartbeat). It spontaneously generates an electrical impulse, which after conducting throughout the heart, causes the heart to contract. Although the electrical impulses are generated spontaneously, the rate of the impulses (and therefore the heart rate) is set by the nerves innervating the sinoatrial node. The sinoatrial node is located in the myocardial wall near where the sinus venarum joins the right atrium (upper chamber); hence sino- + atrial.[1]

Discovery

The sinoatrial node was first discovered by a young medical student, Martin Flack, in the heart of a mole, whilst his mentor, Sir Arthur Keith, was on a bicycle ride with his wife. They made the discovery in a makeshift laboratory set up in a picturesque farmhouse in Kent, England, called Mann's Place. Their discovery was published in 1907.[2][3]

Structure

Location

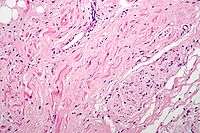

The sinoatrial node is composed of a group of specialised cells positioned in the wall of the right atrium just lateral to the sinus venarum at the junction where the superior vena cava enters the right atrium.[1] The SA node is located in the myocardium just internally to the epicardium. Its deep aspect abuts cardiac myocytes belonging to the right atrium, while its superficial aspect is covered by adipose tissue. It is an elongated structure that extends between 1 and 2 cm on the right from the crista terminalis the crest of the right atrial appendage, and runs posteroinferiorly into the upper part of the terminal groove. SA node fibres are specialized cardiomyocytes that vaguely resemble normal, contractile cardiac myocytes; however, although they possess some contractile filaments they do not contract as robustly. Additionally, SA node fibers are measurably thinner, more tortuous and stain less intensely than cardiac myocytes.

Innervation

The SA node is richly innervated by parasympathetic nervous system fibers (the tenth cranial nerve (CN X: vagus nerve)) and by sympathetic nervous system fibers (T1-4, spinal nerves). This unique anatomical arrangement makes the SA node susceptible to distinctly paired and opposed autonomic influences. At rest, the sinus rate is mostly influenced by vagal discharges or "tone" and on exercise mostly by adrenergic input.

- Stimulation of the vagus nerves (the parasympathetic fibers) causes a decrease in the SA node rate (thereby decreasing the heart rate). The parasympathetic nervous system, through the action of vagus nerve, exerts a negative inotropic effect upon the heart.[4]

- Stimulation via sympathetic fibers causes an increase in the SA node rate (thereby increasing the heart rate and force of contraction). Sympathetic fibers can increase the force of contraction because in addition to innervating the SA and AV nodes, they innervate the atria and ventricles themselves.

Blood supply

The SA node receives blood supply from the SA node artery. Anatomical dissection studies have shown that this supply may be a branch of the right coronary artery in the majority (about 60-70%) of hearts, and a branch of the left coronary artery (usually the left circumflex artery) in about 20-30% of hearts.[5] Rarer variants may include blood supply from both right and left coronary arteries or two branches of the right coronary artery.[6]

Function

Pacemaking

Although some of the heart's cells have the ability to generate the electrical impulses (or action potentials) that trigger cardiac contraction, the sinoatrial node normally initiates it, simply because it generates impulses slightly faster than the other areas with pacemaker potential. Cardiomyocytes, like all muscle cells, have refractory periods following contraction during which additional contractions cannot be triggered; their pacemaker potential is overridden by the sinoatrial or atrioventricular nodes.

In the absence of extrinsic neural and hormonal control, cells in the sinoatrial node (SA node), situated in the upper right corner of the heart, will naturally discharge (create action potentials) upwards of 100 beats/minute.[7] Because the sinoatrial node is responsible for the rest of the heart's electrical activity, it is sometimes called the primary pacemaker.

Clinical significance

Sinus node dysfunction describes an irregular heartbeat caused by faulty electrical signals of the heart. When the heart's sinoatrial node is defective, the heart’s rhythms become abnormal – typically too slow or exhibiting pauses in its function or a combination, and very rarely faster than normal.[8]

Occlusion of the arterial blood supply to the SA node (most commonly due to a myocardial infarction or progressive coronary artery disease) can therefore cause ischaemia and cell death in the SA node. This can disrupt the electrical pacemaker function of the SA node, and can result in sick sinus syndrome.

If the SA node does not function, or the impulse generated in the SA node is blocked before it travels down the electrical conduction system, a group of cells further down the heart will become its pacemaker.[9] This center is typically represented by cells inside the atrioventricular node (AV node), which is an area between the atria and ventricles, within the atrial septum. If the AV node also fails, Purkinje fibers are occasionally capable of acting as the default or "escape" pacemaker. The reason Purkinje cells do not normally control the heart rate is that they generate action potentials at a lower frequency than the AV or SA nodes.

Additional images

-

Heart; conduction system (SA node labeled 1)

-

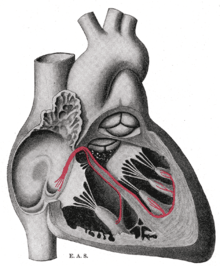

Schematic representation of the atrioventricular bundle

See also

References

- 1 2 Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ↑ Silverman, M.E.; Hollman, A. (1 October 2007). "Discovery of the sinus node by Keith and Flack: on the centennial of their 1907 publication". Heart (journal). 93 (10): 1184–1187. doi:10.1136/hrt.2006.105049. PMC 2000948

. PMID 17890694.

. PMID 17890694. - ↑ Boyett MR, Dobrzynski H (June 2007). "The sinoatrial node is still setting the pace 100 years after its discovery". Circ. Res. 100 (11): 1543–5. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.101101. PMID 17556667.

- ↑ Lewis, M. E.; Al-Khalidi, A. H.; Bonser, R. S.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Morton, D.; Paterson, D.; Townend, J. N.; Coote, J. H. (2001). "Vagus nerve stimulation decreases left ventricular contractilityin vivoin the human and pig heart". The Journal of Physiology. 534 (2): 547–52. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00547.x. PMC 2278718

. PMID 11454971.

. PMID 11454971. - ↑ Pejković, B.; Krajnc, I.; Anderhuber, F.; Kosutić, D. (2008). "Anatomical aspects of the arterial blood supply to the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes of the human heart". The Journal of international medical research. 36 (4): 691–698. doi:10.1177/147323000803600410. PMID 18652764.

- ↑ Onciu, M.; Tuţă, L. A.; Baz, R.; Leonte, T. (2006). "Specifics of the blood supply of the sinoatrial node". Revista medico-chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici si Naturalisti din Iasi. 110 (3): 667–673. PMID 17571564.

- ↑ AnatomySAnode

- ↑ Sinus node dysfunction Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- ↑ Junctional Rhythm at eMedicine

External links

- Anatomy figure: 20:06-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The conduction system of the heart."

- Diagram at gru.net

- thoraxlesson4 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (thoraxheartinternalner)

- http://www.healthyheart.nhs.uk/heart_works/heart03.shtml