Philippine presidential election, 1986

| | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

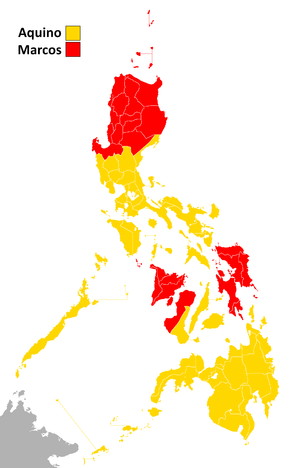

| Election results per province/city. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Philippines |

|

Legislature

|

|

Constitutional Commissions |

The 1986 Philippine Presidential Election, or more popularly known as The Snap Elections, were held on 7 February 1986. This is subject to debate as there are many discrepancies on the number of votes and the winner of the elections. The two main candidates, Corazon C. Aquino and Ferdinand E. Marcos, representing the PDP-Laban party and the KBL party respectively both won the election due to different counting by NAMFREL and the COMELEC. It is believed that Marcos committed fraud in the tallying of votes. Following this, both the United States of America and the Church gave statements supporting Aquino's accession as President. This event is known to be the catalyst for the end of Martial Law and the Marcos Regime as it brought about the People Power Revolution.

Background

Role of the Media

The courage and the essential goodness of Corazón Aquino was so impressive in her battle against enormous odds. And the bravery of her followers— many of whom were killed as they pursued their belief in a true democracy... And then there was this: the role of the press, print and electronic. Through television cameras and newspapers, the whole world was watching. President Marcos could lie and cheat, but in the end he could not hide.[1]

—Tom Brokaw, NBC Nightly News

The assassination of Senator Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. on August 21, 1983 revived the oppositionist press, and not far behind it did the pro-Marcos or so called crony press retaliate. Both catered to the intense news-hunger of the Filipino people, but it was a smaller group of reporters who delivered the crucial blow to President Ferdinand E. Marcos' image, with rumors circulating about Marcos' hidden wealth and war record. An example of this would be the article written by Eduardo Lachica in December 1982. It stirred interest after being published in The Asian Wall Street Journal on the alleged Marcos property holdings in New York.[1]

By late January 1985, the pursuit for the truth behind the rumors began with Lewis M. Simons, a Tokyo-based correspondent for the San Jose Mercury News, who sent a memo to his desk editor, Jonathan Krim. There have been incessant speculations of Philippine "capital flight" that not only involved Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos themselves, but also government officials and friends of the first family. Simons provided Krim with a list of names, telling him to look into Philippine investments in the San Francisco Bay area. Krim handed over several clips (including Lachica's article) and miscellaneous letters from the Filipino exile community to the investigative reporter Pete Carey attached with a note, "Look into this." Carey began his paper trail after setting up his personal computer and a telephone modem as well as using real-estate data bases to acquire both California and out-of-state records. Another method he used in tracking the story were his interviews with the members of the Filipino exiled opposition who were divided between those who were resolute in helping him and those who deemed themselves apolitical, fearing reprisals if they spoke. In an interview, Carey says, "I kept telling them, 'I'm not interested in quoting people, I'm not going to use yours or any names. I'm interested in documentary evidence,' That convinced people...." Due to budgetary concerns, He continued his trail by exploring records in New York and Chicago through telephone. At a later date, Katherine Ellison from the San Francisco Bureau, who Carey dubs as another "great investigative reporter," joined the group as they conducted interviews and convinced reluctant locals to provide essential information.[1]

On June 23–25, 1985, the Mercury News series under the by-lines of Carey, Ellison, and Simons elicited a staggering response after revealing a list of names, showing how the Filipino elite had illegally invested millions in the U.S., why real estate conditions made California a prime investment territory, and how capital flight fueled Philippine insurgency. Meanwhile local publications in the Philippines such as Malaya, Veritas, Business Day, and Mr. and Mrs. all reprinted the series. There were protests on the streets, attempts by the National Assembly's opposition minority to file an impeachment hearing (which was quickly annulled) while President Marcos was forced to order an impartial inquiry (though it lasted briefly).[1]

The international clamor surprised the three Mercury News investigators with Carey commenting, "There's a vast difference between simple allegations and something with a factual, documentary basis," he says. "It provokes a totally different psychological reaction in the readers. Gossip stirs their apathy; facts galvanize them to action."[1]

After the successful publication of the series, newer articles were produced by the Mercury News team, among other things, such as how the Manila elitists smuggled fortunes, in the form of American currency, out of the country. More reporters from The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times developed other angles as well. The most significant were those uncovered by Times' Jeff Gerth, who wrote on the misuse of American aid money by the Marcos' administration. Although President Marcos continued to deny these allegations, it did little to avert the consequences. His support in the congress quickly dissipated while news of his misrule endangered U.S. military interests.[1] Though revelations of Marcos' hidden wealth disparaged him in America, in the Philippines, it was the truth of his war records that did him in. During a campaign in Manila's Tondo district, Marcos retorted:[2]

I don't know where they got such foolishness. You who are here in Tondo and fought under me and who were part of my guerrilla organization, you will be the ones to answer these people, these crazy individuals, especially the foreign press who keep asking all these questions.

—Ferdinand Marcos, 1986

The story was researched by a Yale-trained historian, Alfred McCoy, who had been at work on a book about the Philippines during World War II when he was sidetracked by the questionable information concerning Marcos' wartime service. In the summer of 1985, official army documents were taken from the National Archives in Washington and albeit declassified, these were never released publicly. McCoy later told the reporters that he was "stunned," since the documents proved that most of the Philippine President's war record— a series of exploits against the Japanese that Marcos used to advance in postwar national politics —was fraudulent. He shared his findings to American reporters who provided verification and later, published their own stories. McCoy further arranged for the news to be published in Veritas on January 24, 1986, where the Philippine election campaign moved towards its end, considering the act to be a fine sense of political timing.[1]

A Call for Reforms

The communist insurgency in the Philippines has become a major challenge to the Philippine government. It has grown in recent years against the background of a serious decline in popular confidence in the leadership of the authoritarian administration of President Ferdinand Marcos— a trend worsened by developments following the assassination of political opposition leader Benigno Aquino in August 1983 —and the substantial real drop in popular living standards due to deteriorating Philippine economic conditions. The communists are now able to field increasing numbers of political operatives and armed insurgents in all parts of the country, while the Philippine government has been unable to implement a sufficiently effective counterinsurgency program.[3]

—U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (1985)

Mainly coming from the U.S. and from a host of cause-oriented groups, the demand for reforms in the Marcos administration were the most prominent developments in 1985. Pressures for government rectification fell into these three areas:[4]

- Revitalization of democratic processes together with the development of an electoral code to ensure free and honest elections;

- Restoration of a free market economy; and

- Military re-invigoration of [military] professionalism and discipline so as to effectively combat the growing insurgency problem.

President Marcos, who continued his role as a guileful politician, has firmly resisted instituting genuine reforms in his attempt to circumvent the Americans and the opposition. In general, reforms have bordered on what critics call "cosmetic" settlements. President Marcos maintained using his authoritarian powers while his cronies monopolized key agricultural sectors.[4]

Organizing the 1986 Philippine Elections

On November 4, 1985, Sam Donaldson and George Will interviewed President Ferdinand E. Marcos on the American Broadcasting Company political affairs program, This Week with David Brinkley.[5][6] Marcos was being asked about his policies and support when, without warning, he announced that he would hold a Snap Elections on February 7, 1986, a year earlier than the supposed 1987 elections. Marcos said that in the Snap Elections, the vice president would also be determined. Also, the final decision regarding the elections would be determined by the National Assembly.

Ten petitions were filed before Supreme Court that questioned the constitutionality of the 1986 snap elections or the Batas Pambansa Blg. 883. The petitioners argued that the BP 883 violates Article VII Sec. 9 of the constitution, which specifies that the holding of emergency elections "in case of permanent disability, death, removal from office, or resignation of the President." However, elements of the opposition argued that the president's post-dated resignation last November 11, 1985 did not create a real vacancy in the presidency and was merely a deception. The petitioners' case was rejected by a 7-5 vote in the Supreme Court. Marcos would remain president throughout the election, which was an action that seemed to be in conflict with the constitution at the time.[4]

Marcos declared the early elections since he believed that this would solidify the support of United States, silence the protests and criticisms both in the Philippines and the United States, and finally put the issues regarding the death of Benigno Aquino Jr. to rest.[7]

The opposition saw two problems regarding the announcement of Marcos. First is the credibility of the announcement since at the time two-thirds of the national assembly were from KBL, which means that they could decide not to push through with the Snap Elections. This would then give Marcos an image that he was willing to entertain opposers, which would then contribute to his popularity. Second problem is that the opposition was yet to choose a single presidential candidate to who had a chance to win.[7] This posed a problem for them since the opposition were yet to be united, supporting only one presidential candidate.

For the opposition, they were torn between the widow of Benigno Aquino Jr., Corazon "Cory" Aquino, and Doy Laurel, son of President Jose P. Laurel. Cardinal Jaime Sin talked to both the potential candidates. Cory was hesitant to run since she believed that she was not the best and most able choice. She also feared the loss of privacy once she enters the political arena. Cory agreed to run if there was a petition campaign with at least a million signatures supporting her as a presidential candidate. Doy on the other hand, was earnest in running as president since he believed his family background, training, and experience have prepared him for the presidency. After talks, Doy Laurel decided to run as Cory Aquino's running mate.

On 3 December 1985, the Batasang Pambansa passed a law setting the date of the election on 7 February 1986.[8] Marcos chose Arturo Tolentino as his running mate. Marcos' conditions for his running mate was that "He should never disagree with the president."

Campaign

The campaign period started from December 19, 1985 to February 5, 1986. A total of forty-five (45) days

During the campaign period, Cory Aquino promised to run a government that would be the exact opposite of the Marcos administration at that time. The battle-cry, “ Tama na! Sobra na! Palitan na!” loosely translated, “ Enough is enough! Time for a change in leadership!” and wearing any article of clothing that was yellow were the statements of the support of the UNIDO party.[9] The Aquino-Laurel campaign was believed to center around the principle of morality in leadership.[10]

The campaign of Corazon Aquino and Salvador Laurel had numerous help from the church. One of them would be Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin who issued a pastoral letter on the snap elections urging the people to not fall for vote buying during the elections on 19 December 1985. On 28 December 1985, Cardinal Sin made a tract, “Guidelines on Christian Conduct During Elections,” which had a part that said:

"Do not sell your vote. The acceptance of money to vote for a candidate (a practice we do not encourage) does not bind you to vote for that candidate. No one is 'obliged to fulfill an evil contact.'"

Eventually, Cardinal Sin reiterated on 19 January 1986 his second pastoral letter on the snap elections, “A Call to Conscience.” This second letter provided significant amount of information about the statement issued by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines on 25 January 1986, “We Must Obey God Rather Than Men.”

On 5 February, the last day of the campaign period, Jaime Cardinal Sin revealed that he has supported Cory as her partisan as he endorsed Cory that she , “will also make a good president.”[11]

In the other hand, Ferdinand Marcos displayed the idea of a “macho” president by ridiculing not only Cory saying how she is just a woman and a “know-nothing” (Walang alam ‘yan!) but also including in his campaign speeches how Filipino women's proper place would be in the bedroom.[9] The Marcos-Tolentino campaign was believed to mainly center around “issues of communism and competence.”[10]

As the election campaign continued, Marcos was able to campaign in selected key cities while Aquino was able to campaign intensively and extensively, even going to remote places from the north of the Philippines to the south of the Philippines. The Aquino campaign concluded a rally that is believed to have 800 000 participants wearing yellow in Rizal Park and Roxas Boulevard forming a “sea of yellow.”[10]

Results

About 85,000 precincts opened at seven o’clock in the morning of Election Day.[12] Each precincts was administered by a Board of Election Inspectors (BEI), wherein they were tasked to overlook the manner of voting. However, the BEI did not continuously abide by the stipulated voting procedure, which raised the impression of fraud.

Voting period were also scheduled to close at three o’clock in the afternoon but was extended to give way for people who were in line. Counting of the ballots followed and most precincts was able to finish by six o’clock in the evening.[13]

Results showed that a huge number of eligible electorates did not vote. Out of the 26 million registered voters, only 20 million ballots were cast. This showed a decreased percentage of voters from the 1984 election, which had 89% of registered voters casted their ballot, to around 76% during the snap election.[13]

| Number of Voters in the 1986 Election | |

|---|---|

| Number of registered voters | 26,181,829 |

| Actual Number of votes canvassed by the Batasan | 20,150,160 |

| Percentage of Actual to Registered Voters | 76.96% |

A number of disenfranchised voters were evident during the snap election.

| Estimated number of Disenfranchised Voters[13] | |

|---|---|

| 1984 Percentage of Actual to Registered Voters | 89% |

| 1986 Number of voters base from the 1984 percentage | 23,422,264 |

| Actual Number of votes canvassed by the Batasan | 20,150,160 |

| Estimated number of disenfranchised voters | 3,272,104 |

President

| COMELEC[13] | NAMFREL[14] | |||||

| Marcos | Aquino | Canoy | Padilla | Marcos | Aquino | |

| National Capital Region | 1,394,815 | 1,614,662 | 794 | 10,687 | 1,312,592 | 1,530,678 |

| Region I | 1,239,825 | 431,877 | 282 | 3,399 | 578,997 | 282,506 |

| Region II | 856,026 | 139,666 | 111 | 381 | 188,556 | 105,934 |

| Region III | 1,011,860 | 1,008,157 | 243 | 2,268 | 647,318 | 761,771 |

| Region IV | 1,190,804 | 1,425,143 | 336 | 3,831 | 757,689 | 995,238 |

| Region V | 433,809 | 761,538 | 258 | 376 | 354,784 | 634,453 |

| Region VI | 902,682 | 777,312 | 386 | 244 | 582,075 | 561,177 |

| Region VII | 773,604 | 827,912 | 4,012 | 394 | 535,363 | 722,631 |

| Region VIII | 627,868 | 411,284 | 475 | 213 | 527,076 | 372,179 |

| Region IX | 540,570 | 365,195 | 3,686 | 505 | 234,064 | 256,819 |

| Region X | 563,547 | 519,841 | 8,244 | 223 | 293,799 | 308,751 |

| Region XI | 609,540 | 662,799 | 13,413 | 773 | 353,413 | 404,124 |

| Region XII | 662,247 | 346,330 | 1,801 | 358 | 166,636 | 222,418 |

| Total | 10,807,197 | 9,291,716 | 34,041 | 23,652 | 6,532,362 | 7,158,679 |

The COMELEC proclaimed Marcos as the winner with more than 1.5 million voted greater than the next contender, Cory Aquino. In the COMELEC's tally a total of 10,807,197 votes was for Marcos alone. Conversely, NAMFREL's tally had Aquino winning with more than half a million lead.

Vice President

| COMELEC[13] | NAMFREL[14] | ||||||

| Tolentino | Laurel | Kalaw | Arienda | Tolentino | Laurel | Kalaw | |

| National Capital Region | 1,411,863 | 1,366,162 | 219,763 | - | 1,323,201 | 1,288,285 | 231,318 |

| Region I | 1,173,312 | 394,255 | 96,257 | - | 552,624 | 246,681 | 67,111 |

| Region II | 825,886 | 150,538 | 8,111 | - | 176,739 | 102,537 | 3,879 |

| Region III | 984,045 | 920,095 | 104,957 | - | 664,601 | 741,294 | 91,386 |

| Region IV | 853,600 | 1,691,011 | 58,524 | - | 504,364 | 1,221,014 | 44,349 |

| Region V | 388,961 | 774,336 | 25,654 | - | 328,526 | 653,025 | 23,772 |

| Region VI | 814,910 | 783,183 | 56,910 | - | 542,428 | 573,447 | 44,362 |

| Region VII | 790,432 | 799,565 | 7,571 | - | 552,760 | 694,377 | 7,296 |

| Region VIII | 606,648 | 403,660 | 21,931 | - | 506,552 | 377,735 | 22,243 |

| Region IX | 531,457 | 359,502 | 5,192 | - | 233,765 | 252,371 | 4,843 |

| Region X | 552,528 | 519,502 | 7,451 | - | 397,572 | 421,107 | 7,543 |

| Region XI | 599,462 | 635,701 | 37,640 | - | 422,444 | 464,813 | 33,565 |

| Region XII | 601,020 | 375,595 | 12,224 | - | 179,717 | 213,239 | 7,922 |

| Total | 10,134,124 | 9,173,105 | 662,185 | 35,974 | 6,385,293 | 7,249,925 | 589,589 |

| Summary of Election Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| COMELEC[13] | |||

| Ferdinand Marcos | Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (New Society Movement) | 10,807,197 | 53.62% |

| Corazon Aquino | United Nationalist Democratic Organization | 9,291,716 | 46.10% |

| Reuben Canoy | Social Democratic Party | 34,041 | 0.17% |

| Narciso Padilla | Movement for Truth, Order and Righteousness | 23,652 | 0.12% |

| Arturo Tolentino | Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (New Society Movement) | 10,134,130 | 50.65% |

| Salvador Laurel | United Nationalist Democratic Organization | 9,173,105 | 45.85% |

| Eva Estrada Kalaw | Liberal (Kalaw Wing) | 662,185 | 3.31% |

| Roger Arienda | Movement for Truth, Order and Righteousness | 35,974 | 0.18% |

| NAMFREL[14] | |||

| Ferdinand Marcos | Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (New Society Movement) | 6,532,362 | - |

| Corazon Aquino | United Nationalist Democratic Organization | 7,158,679 | - |

| Arturo Tolentino | Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (New Society Movement) | 6,385,293 | - |

| Salvador Laurel | United Nationalist Democratic Organization | 7,249,925 | - |

| Eva Estrada Kalaw | Liberal (Kalaw Wing) | 589,589 | - |

Aftermath

The final results of the February 7, 1986 Snap Elections led to the popular belief that the polls were tampered and considered an electoral fraud. The following days consisted of countless debates and actions as a sign of aversion to the result. Violence was at a peak. Anyone who got in the way would get murdered even in broad daylight. But in the end, as according to the International Observer Delegation, the "election of the February 7 was not conducted in a free and fair manner" due to the influence and power of the administration of Ferdinand Marcos. The International Observer Delegation reaffirmed that the proclamation of the victors of the leection were invalid because the Batasan “ignored explicit provisions of the Philippine Electoral Code [Batas Pambansa Blg. 881] requiring that the tampered or altered Election Returns be set aside during the final counting process, despite protests by representatives of the opposition parts”. After further investigation, a multinational team of observers cited cases of vote-buying, intimidation, snatching of ballot boxes, tampered election returns and the disenfranchisement of thousands of voters[15]

One day after the Snap Elections, Cory Aquino was taking the lead according to the NAMFREL's tally but was short lived when Marcos' tally began leading. There were countless of daily protests and street demonstrations fueled by the government's counting of the tally and the site of Marcos winning the polls. On February 9, Linda Kapunan led 30 computer technicians who were manning the COMELEC tabulation machines to walk out of their job posts and join the protests who were accusing the current administration with tampering results. They found safety in the Baclaran Churhc. This was oe of the early “sparks” of the People Power Revolution.[16]

Lina Kapunan was the wife of Lt. Col Eduardo Kapunan, a leader of Reform the Armed Forces Movement which is an group that plotted to attack the Malacañang Palace and kill Marcos and his family. There were suspicions that the walk out of the 30 computer technicians may have been linked to the group of her husband.[16]

After the snap elections, word of faulty elections broke out into the international setting. That being said, prominent figures such as Reagan started to meddle in our government by saying, “hard evidence” of fraud was lacking. Aware of the United State’s intentions in insisting that elections were clean and peaceful, Corazon Aquino responded to Reagan by asking if the country’s “friends abroad [can] set aside short sighted self interest and stop supporting the failing dictator”.[16] As the international reputation of the Philippines continues to go down, the Philippine peso fell drastically to an “all-time low of P20 to a dollar” as of February 2.

As of February 14, The Catholic Bishop's Conference of the Philippines President Cardinal Ricardo Vidal released a declaration in lieu of the Philippine Church Hierarchy stating that "a government does not of itself freely correct the evil it has inflicted on the people then it is our serious moral obligation as a people to make it do so."[17] This meant that power attained through dirty means such as through cheating and fraud would have no moral basis. The declaration also asked "every loyal member of the Church, every community of the faithful, to form their judgment about the February 7 polls" telling all the Filipinos "[n]ow is the time to speak up.

Corazon Aquino called for a “victory rally” to boycott “crony media, seven banks, Rustan’s department store, and San Miguel Corporation. Large corporations that were believed to be “partly or wholly owned by known Marcos cronies”. Due to the boycotts, many of this large corporations lost sales. There was a significant rise in deposit withdrawals in large and prominent banks made by even the clergy class. The value of San Miguel shares dropped to P11.50 per share and P14.50 per share for A and B shares respectively.[16]

As of February 19, “The US Senate voted in favor of the fact that the declaration that the snap election in the Philippines by widespread fraud”. It seems as if the tables have turned and foreign groups such as the American bishops are no longer in favor of Marcos but of the protest groups instead. Even Reagan, who at first urged Cory to plead that he be on the right side of the situation, put the foreign aid for the Philippines in a temporary suspension for as long as “Marcos remained in office”. Diplomats from countries such as Austria, Switzerland, Ireland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Japan, Britain, Italy, Denmark and West Germany were all pressing for Cory’s seat in the Malacañang.[16]

Seeing the foreign parties turning their backs on him, “Marcos admitted he was nervous about the decisions” on February 21. To top this off, prominent figures in the government such as Juan Ponce Enrile, as the Defense Minister and Armed Forces Vice-Chief of Staff General Fidel Ramos resigned from his posts. After their resignation, they secluded themselves within the military and police headquarters of Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame respectively, which led up ot the People Power Revolution from February 22–25 of February. The turn of the military against Marcos assured that Marcos will not be used military threat to his people anymore. They also assured Aquino that she will have the support of the military incase Marcos does not step down from his position.

The snap elections and its aftermath are dramatized in the 1988 film A Dangerous Life.

See also

- Commission on Elections

- Politics of the Philippines

- Philippine elections

- President of the Philippines

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bain, David Haward (1986). "LETTER FROM MANILA.". Columbia Journalism Review. 25: 28–31 – via Communication & Mass Media Complete, EBSCOhost.

- ↑ Mydans, Seth (January 24, 1986). "MARCOS SAYS REPORT CASTING DOUBT ON WAR EXPLOITS IS 'FOOLISHNESS'". World. The New York Times. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Rood, Steven (1987). Baguio Citizen Response to the February 1986 Snap Election and Revolution. Baguio City: Cordillera Studies Center, University of the Philippines College Baguio. pp. 4–5 – via Rizal Library’s OPAC.

- 1 2 3 Villegas, Bernardo M. (1986). "The Philippines in 1985: Rolling with the Political Punches". Asian Survey. 26 (2): 127–129. JSTOR 10.2307/2644448 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Russell, George (2005-04-18). "The Philippines: I'm Ready, I'm Ready". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ↑ "Philippines - The Snap Election and Marcos's Ouster". www.country-data.com. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- 1 2 "Turmoil, transition...triumph? The democratic revolution in the Philippines.". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- ↑ "B.P. 883". www.lawphil.net. Retrieved 2016-11-15.

- 1 2 Villacorte, Rolando (1988). The Real Hero of EDSA. Quezon City: Berligui Typographics Corporation. pp. 17–19.

- 1 2 3 Santos, Antonio (1987). Power politics in the Philippines: The Fall of Marcos. Quezon City: Center for Social Research. pp. 22–25.

- ↑ Escalante, Salvador (2000). The 1986 EDSA Uprising: In Retrospect. Quezon City: Katotohanan At Katarungan Foundation Inc. pp. 21–23.

- 1 2 "Nation commemorates 25th anniversary of the 1986 Snap Presidential Election" (PDF). Election Monitor. Volume 1- Issue No. 61. 2011 – via NAMFREL.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Atwood, J. Brian; Schuette, Keith E. "A Path to Democratic Renewal" (PDF): 350 – via National Democratic Institute for International Affairs and National Republican Institute for International Affairs.

- 1 2 3 "NAMFREL". www.namfrel.com.ph. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ↑ (PDF) http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABK494.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Santiago, Angela Stuart (1995). Chronology of Revolution 1986. Philippines: Foundation for Worldwide People Power, Inc. pp. 12–14.

- ↑ http://www.cbcponline.net/documents/1980s/1986-post_election.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

- The Philippine Electoral Almanac, prepared by the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office (PCDSPO)

- Corazon C. Aquino page from the Presidential Museum and Library (also under the PCDSPO), contains results of the 1986 snap elections from the Philippine Electoral Almanac

- An Act Calling A Special Election For President And Vice-president, Providing For The Manner Of The Holding Thereof, Appropriating Funds Therefor, And For Other Purposes, Batas Pambansa Blg. 883 (National Law No. 883)

- Official website of the Commission on Elections

- "A Path to Democratic Renewal" - A Report on the February 7, 1986 Presidential Election in the Philippines by the International Observer Delegation

- 1986 Philippines Elections

- Photo Gallery of 1986 Snap Elections from the National Citizens' Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL)