Social value orientations

In social psychology, social value orientation (SVO) is a person's preference about how to allocate resources (e.g. money) between the self and another person. SVO corresponds to how much weight a person attaches to the welfare of others in relation to the own. Since people are assumed to vary in the weight they attach to other peoples' outcomes in relation to their own, SVO is an individual difference variable. The general concept underlying SVO has become widely studied in a variety of different scientific disciplines, such as economics, sociology, and biology under a multitude of different names (e.g. social preferences, other-regarding preferences, welfare tradeoff ratios, social motives, etc.).

Historical background

The SVO construct has its history in the study of interdependent decision making, i.e. strategic interactions between two or more people. The advent of Game theory in the 1940s provided a formal language for describing and analyzing situations of interdependence based on utility theory. As a simplifying assumption for analyzing strategic interactions, it was generally presumed that people only consider their own outcomes when making decisions in interdependent situations, rather than taking into account the interaction partners' outcomes as well. However, the study of human behavior in social dilemma situations, such as the Prisoner's dilemma, revealed that some people do in fact appear to have concerns for others.

In the Prisoner's dilemma, participants are asked to take the role of two criminals. In this situation, they are to pretend that they are a pair of criminals being interrogated by detectives in separate rooms. Both participants are being offered a deal and have two options. That is, the participant may remain silent or confess and implicate his or her partner. However, if both participants choose to remain silent, they will be set free. If both participants confess they will receive a moderate sentence. Conversely, if one participant remains silent while the other confesses, the person who confesses will receive a minimal sentence while the person who remained silent (and was implicated by their partner) will receive a maximum sentence. Thus, participants have to make the decision to cooperate with or compete with their partner.

When used in the lab, the dynamics of this situation are stimulated as participants play for points or for money. Participants are given one of two choices, labeled option C or D. Option C would be the cooperative choice and if both participants choose to be cooperative then they will both earn points or money. On the other hand, Option D is the competitive choice. If just one participants chooses option D, that participant will earn points or money while the other player will lose money. However, if both participant pick D, then both of them will lose money. In addition to displaying participant's social value orientations, it also displays the dynamics of a mixed-motives situation.[1]

From behavior in strategic situations it is not possible, though, to infer peoples' motives, i.e. the joint outcome they would choose if they alone could determine it. The reason is that behavior in a strategic situation is always a function of both peoples' preferences about joint outcomes and their beliefs about the intentions and behavior of their interaction partners.

In an attempt to assess peoples' preferences over joint outcomes alone, disentangled from their beliefs about the other persons' behavior, David M. Messick and Charles G. McClintock in 1968[2] devised what has become known as the decomposed game technique. Basically, any task where one decision maker can alone determine which one out of at least two own-other resource allocation options will be realized is a decomposed game (also often referred to as dictator game, especially in economics, where it is often implemented as a constant-sum situation).

By observing which own-other resource allocation a person chooses in a decomposed game, it is possible to infer that person's preferences over own-other resource allocations, i.e. social value orientation. Since there is no other person making a decision that affects the joint outcome, there is no interdependence, and therefore a potential effect of beliefs on behavior is ruled out.

To give an example, consider two options, A and B. If you choose option A, you will receive $100, and another (unknown) person will receive $10. If you choose option B, you will receive $85, and the other (unknown) person will also receive $85. This is a decomposed game. If a person chooses option B, we can infer that this person does not only consider the outcome for the self when making a decision, but also takes into account the outcome for the other.

SVO conceptualization

When people seek to maximize their gains, they are said to be proself. But when people are also concerned with other's gains and losses, they are said to be prosocial. There are four categories within SVO. Individualistic and competitive SVOs are proself while cooperative and altruistic SVOs are prosocial:[3]

- Individualistic orientation: Members of this category are concerned only with their own outcomes. They make decisions based on what they think they will personally achieve, without concern for others outcomes. They are focused only on their own outcomes and therefore do not get involved with other group members. they neither assist nor interfere. However their actions may indirectly impact other members of the group but such impact is not their goal.

- Competitive orientation: Competitors much like individualists strive to maximize their own outcomes, but in addition they seek to minimize others outcomes. disagreements and arguments are viewed as win-lose situations and competitors find satisfaction in forcing their ideas upon others. A competitor has the belief that each person should get the most they can in each situation and play to win every time. Those with competitive SVOs are more likely to find themselves in conflicts.[4] Competitors cause cooperators to react with criticism to their abrasive styles. However, competitors rarely modify their behavior in response to these complaints because they are relatively unconcerned with maintaining interpersonal relations.

- Cooperative orientation: Cooperators tend to maximize their own outcomes as well as other's outcomes. They prefer strategies that generate win-win situations. When dealing with other people they believe that it is better if everyone comes out even in a situation.

- Altruistic orientation: altruists are motivated to help other who are in need. Members of this category are low in self-interest. They willingly sacrifice their own outcomes in the hopes of helping others achieve gain.

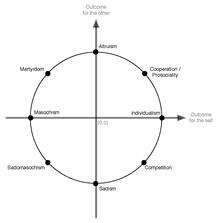

However, in 1973 Griesinger and Livingston [5] provided a geometric framework of SVO (the SVO ring, see Figure 1) with which they could show that SVO is in principle not a categorical, but a continuous construct that allows for an infinite number of social value orientations.

The basic idea was to represent outcomes for the self (on the x-axis) and for the other (on the y-axis) on a Cartesian plane, and represent own-other payoff allocation options as coordinates on a circle centered at the origin of the plane. If a person chooses a particular own-other outcome allocation on the ring, that person's SVO can be represented by the angle of the line starting at the origin of the Cartesian plane and intersecting the coordinates of the respective chosen own-other outcome allocation.

If, for instance, a person would choose the option on the circle that maximizes the own outcome, this would refer to an SVO angle of , indicating a perfectly individualistic SVO. An angle of would indicate a perfectly cooperative (maximizing joint outcomes) SVO, while an angle of would indicate a perfectly competitive (maximizing relative gain) SVO. This conceptualization indicates that SVO is a continuous construct, since there is an infinite number of possible SVOs, because angular degrees are continuous.

This advancement in the conceptualization of the SVO construct also clarified that SVO as originally conceptualized can be represented in terms of a utility function of the following form

,

where is the outcome for the self, is the outcome for the other, and the parameters indicate the weight a person attaches to the own outcome () and the outcome for the other ().

SVO measurement

Several different measurement methods exist for assessing SVO.[7] The basis for any of these measures is the decomposed game technique, i.e. a set of non-constant-sum dictator games. The most commonly used SVO measures are the following.

Ring Measure

The Ring measure was devised by Wim B. G. Liebrand in 1984[6] and is based on the geometric SVO framework proposed by Griesinger and Livingson in 1973.[5] In the Ring measure, subjects are asked to choose between 24 pairs of options that allocate money to the subject and the "other". The 24 pairs of outcomes correspond to equally spaced adjacent own-other-payoff allocations on an SVO ring, i.e. a circle with a certain radius centered at the origin of the Cartesian plane. The vertical axis (y) measures the amount of points or money allocated to the other and the horizontal axis (x) measures the amount allocated to the self. Each pair of outcomes corresponds to two adjacent points on the circle. Adding up a subject's 24 choices yields a motivational vector with a certain length and angle. The length of the vector indicates the consistency of a subject's choice behavior, while the angle indicates that subject's SVO. Subjects are then categorized into one out of eight SVO categories according to their SVO angle, given a sufficiently consistent choice pattern. This measure allows for the detection of uncommon pathological SVOs, such as masochism, sadomasochism, or martyrdom, which would indicate that a subject attaches a negative weight () to the outcome for the self given the utility function described above.

Triple-Dominance Measure

The triple-dominance measure[8] is directly based on the use of decomposed games as suggested by Messick and McClintock (1968).[2] Concretely, the triple-dominance measure consists of nine items, each of which asks a subject to choose one out of three own-other-outcome allocations. The three options do have the same characteristics in each of the items. One option maximizes the outcome for the self, a second option maximizes the sum of the outcomes for the self and the other (joint outcome), and the third option maximizes the relative gain (i.e. the difference between the outcome for the self and the outcome for the other). If a subject chooses an option indicating a particular SVO in at least six out of the nine items, the subject is categorized accordingly. That is, a subject is categorized as cooperative/prosocial, individualistic, or competitive.

SVO Slider Measure

The Slider measure[9] assess SVO on a continuous scale, rather than categorizing subjects into nominal motivational groups. The instrument consists of 6 primary and 9 secondary items. In each item of the paper-based version of the Slider measure, a subject has to indicate her most preferred own-other outcome allocation out of nine options. From a subject's choices in the primary items, the SVO angle can be computed. There is also an online version of the Slider measure, where subjects can slide along a continuum of own-other payoff allocations in the items, allowing for a very precise assessment of a person's SVO. The secondary items can be used for differentiating between the motivations to maximize the joint outcome and to minimize the difference in outcomes (inequality aversion) among prosocial subjects. The SVO Slider Measure has been shown to be more reliable than previously used measures, and yields SVO scores on a continuous scale.[9]

Stylized SVO facts

SVO has been shown to be predictive of important behavioral variables, such as:

- cooperative behavior in social dilemmas [10]

- helping behavior [11]

- donation behavior [12]

- proenvironmental behavior[13]

- negotiation behavior [14]

Furthermore, it has been shown that individualism is prevalent among very young children, and that the frequency of expressions of prosocial and competitive SVOs increases with age. Among adults, it has been shown repeatedly that prosocial SVOs are most frequently observed (up to 60 percent), followed by individualistic SVOs (about 30-40 percent), and competitive SVOs (about 5-10 percent). Evidence also suggests that SVO is first and foremost determined by socialization, and that genetic predisposition plays a minor role in SVO development.[7]

SVO from a broader perspective

The SVO construct is rooted in social psychology, but has also been studied in other disciplines, such as economics.[15] However, the general concept underlying SVO is inherently interdisciplinary, and has been studied under different names in a variety of different scientific fields (see introduction section); it is the concept of distributive preferences. Originally, the SVO construct as conceptualized by the SVO ring framework[5] did not include preferences such as inequality aversion, which is a distributive preference heavily studied in experimental economics. This particular motivation can also not be assessed with commonly used measures of SVO, except with the SVO Slider Measure.[9] The original SVO concept can be extended, though, by representing peoples' distributive preferences in terms of utility functions, as is standard in economics. For instance, a representation of SVO that includes the expression of a motivation to minimize differences between outcomes could be formalized as follows.[16]

.

Several utility functions as representations of peoples' concerns for the welfare of others have been devised and used (for a very prominent example, see Fehr & Schmidt, 1999[17]) in economics. It is a challenge for future interdisciplinary research to combine the findings from different scientific disciplines and arrive at a unifying theory of SVO. Representing SVO in terms of a utility function and going beyond the construct's original conceptualization may facilitate the achievement of this ambitious goal.

References

- ↑ Forsyth, D.R. (2006). Conflict. In Forsyth, D. R., Group Dynamics (5th Ed.) (P. 378-407) Belmont: CA, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

- 1 2 Messick, D. M.; McClintock, C. G. (1968). "Motivational Bases of Choice in Experimental Games". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 4: 1–25. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(68)90046-2.

- ↑ Forsyth, D.R. (2006). Conflict. In Forsyth, D. R., Group Dynamics (5th Ed.) (P. 378-407) Belmont: CA, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

- ↑ Forsyth, D.R. (2006). Conflict. In Forsyth, D. R., Group Dynamics (5th Ed.) (P. 378-407) Belmont: CA, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

- 1 2 3 4 Griesinger, D. W.; Livingston, J. W. (1973). "Toward a model of interpersonal motivation in experimental games". Behavioral Science. 18 (3): 173–188. doi:10.1002/bs.3830180305.

- 1 2 Liebrand, W. B. G. (1984). "'The effect of social motives, communication and group size on behaviour in an n-person multi stage mixed motive game". European Journal of Social Psychology. 14 (3): 239–264. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420140302.

- 1 2 Au, W.T.; Kwong, J.Y.Y. (2004). "Measurement and effects of social-value orientation in social dilemmas". In Suleiman, R.; Budescu, D.; Fischer, I.; Messick, D. Contemporary psychological research on social dilemmas. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–98.

- ↑ Van Lange, P.A.M.; Otten, W.; De Bruin, E.M.N.; Joireman, J.A. (1997). "Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: Theory and preliminary evidence" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 73 (4): 733–746. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.733. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 3 Murphy, R.O.; Ackermann, K.A.; Handgraaf, M.J.J. (2011). "Measuring social value orientation" (PDF). Journal of Judgment and Decision Making. 6 (8): 771–781.

- ↑ Balliet, D.; Parks, C.; Joireman, J. (2009). "Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analysis". Group processes & Intergroup relations. 12 (4): 533–547. doi:10.1177/1368430209105040.

- ↑ McClintock, C.G.; Allison, S.T. (1989). "Social value orientation and helping behavior". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 19 (4): 353–362. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb00060.x.

- ↑ Van Lange, P.A.M.; Bekkers, R.; Schuyt, T.; Van Vugt, M. (2007). "From games to giving: Social value orientation predicts donations to noble causes" (PDF). Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 29 (4): 375–384. doi:10.1080/01973530701665223.

- ↑ Van Vugt, M.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Meertens, R.M. (1996). "Commuting by car or public transportation? A social dilemma analysis of travel mode judgments" (PDF). European Journal of Social Psychology. 26: 373–395. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199605)26:3<373::aid-ejsp760>3.3.co;2-t. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ De Dreu, C.K.W.; Van Lange, P.A.M. (1995). "The impact of social value orientations on negotiator cognition and behavior". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 21: 1178–1188. doi:10.1177/01461672952111006. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Offerman, T.; Sonnemans J.; Schram A. (1996). "Value Orientations, Expectations and Voluntary Contributions in Public Goods". The Economic Journal. Blackwell Publishing. 106 (437): 817–845. doi:10.2307/2235360. JSTOR 2235360.

- ↑ Radzicki, J. (1976). "Technique of conjoint measurement of subjective value of own and other's gains". Polish Psychological Bulletin. 7 (3): 179–186.

- ↑ Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. (1999). "A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 114 (3): 817–868. doi:10.1162/003355399556151.

See also

- Social dilemma

- Cooperation

- Clyde Kluckhohn and his Social Values Orientation Theory

- Experimental economics

- Experimental psychology

- Human behavior

- Motivation

- Rokeach Value Survey

- Social preferences

- Social psychology

- Value system