Sonnet 25

| Sonnet 25 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

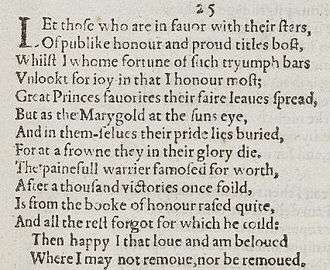

Sonnet 25 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 25 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, and is a part of the Fair Youth sequence. It was published within the Quarto in 1609.

In the sonnet, the poem goes over the speaker's social standing and contentedness in comparison to that of his subject and is among the first of the sequence to deal explicitly with the difference in class between Shakespeare and the subject of the poems. It prefigures the more famous treatment of this difference in Sonnet 29. There is speculation on the similarities of this sonnet and the relationship of Romeo and Juliet.

Paraphrase

This sonnet is addressed to someone in a higher class or status than the poet. The first four lines imply that the subject of this poem is of a courtly status due to the luck of their birth into such high class as implied by the speaker's reference to astrological fortune. Because Shakespeare was not born with the luck and fortune of courtly status, the possibility of ease in success is not afforded to him. The unexpected joy the speaker feels at being looked on favorably by the subject of his sonnet is due to the probability that the speaker was overlooked by those of higher social standing, and therefore, having fewer expectations to live up to. This keeps him from disappointing the subject.

In the next quatrain, the "prince", like a flower, prefers his leaves to be spread in order to receive the praise his pride needs, though he tries to keep that pride hidden. This is to say, he is very open to receiving praise he believes he rightfully deserves. As with the marigold, whose petals close in the absence of the sun, the subject would also close up if his pride, being so fragile as to fall apart at a simple frown, is damaged.

In the final quatrain, the subject of the sonnet has been held in high regard, either for accomplishments or simply for rank, but the high opinion others have of him is fragile. One mistake is all it would take to lower his stock in the public opinion, become disregarded, or be completely written off.

In the final rhyming couplet, the speaker expresses happiness at not being in the same position as the subject of the poem. One mistake, in the speaker's lower place in society, would not cost him what it would cost the subject. The speaker's mistakes could not lower the subject's opinion of the speaker because of their class disparity. In other words, the speaker is happy in mediocrity and happy in his love to the subject.

Context

This sonnet falls in the section of "Q" known as the Fair Youth sequence. In these 126 sonnet, it is believed that Shakespeare is writing about a young man in a homosexual manner (Duncan-Jones). This is visible in Sonnet 20 when Shakespeare writes of the subject having feminine beauty, but is in fact, not a female, but swings between extremes of friendship and love throughout the sequence (Duncan-Jones). How Shakespeare portrays his feelings for the subject of Sonnet 25 can be linked to that of the relationship of Romeo and Juliet, especially within the prologue of the star crossed lovers' play. Romeo even has a sonnet, which is dripping with sentimentality misplaced for his ex Rosaline. Romeo and Juliet was supposed to have been written between 1595 and 1597, while Shakespeare's sonnets were published in 1609.

Petrarchism is a sonnet style that entails complex structure with everyday language and understandable diction. Shakespeare uses this form in few of his sonnets, but employs it in the sonnet that Romeo writes to Rosaline (Earl).

Structure

Sonnet 25 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, formed of three quatrains and a final couplet in iambic pentameter, a type of metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The first line exhibits a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Let those who are in favour with their stars (25.1)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

This sonnet, as originally printed, departs from the English sonnet's typical rhyme scheme, abab cdcd efef gg. Lines nine and eleven (the e lines) do not rhyme; the sonnet's unique rhyme scheme is thus abab cdcd xfxf gg. There is debate on what the purpose of Shakespeare's break in pattern could have been, or whether the existing text incorporates a misprint. The disjoined relationship between lines nine and eleven prompts an exploration of whether or not "fight" or "might" could be substituted for "worth" (Lewis Theobald, Capell in Duncan-Jones). (See Exigesis below.)

Exegesis

Social Standing

This sonnet focuses on satisfaction with one's social standing and how one is seen by his/her peers (Duncan-Jones). The speaker continually praises the subject of the poem, showing how much he appreciates and loves him. The subject is repeatedly referred to as a "warrior" and as "having honour", putting him/her at a higher social standing than the speaker (Booth).

The speaker is contrasting himself, a man who is content living a life free of fame and popularity, to a man well-known and loved by all. He tells how his life is much simpler and fulfilling because he will not waver from his social standing, no matter if he does good or bad, whereas a man in the public's eye can easily fall from grace and be forgotten by everyone (Duncan-Jones).

Astrological References

Shakespeare focuses on the astrological power of fate within this poem, as well. He cites the stars as the luck-giving ones that put the beloved subject of his poem in high court. The reference made to the "favour of the stars" is also a metaphor for the members of the court keeping in favour of the King (Booth). Because the courtly status of the subject of this poem was gifted by the stars and not earned, the place he or she holds is a precarious one. In contrast to some of Shakespeare's other sonnets in the Fair Youth series, Shakespeare welcomes his own mediocrity as a contrast to his subject rather than simply gushing with praise for his subject (Duncan-Jones). John Kerrigan notes the echo of the prologue to Romeo and Juliet in the astrological metaphor of the first quatrain; he notes that the image severs reward from justice, making fortune a mere caprice. "Unlooked for" has occasioned some comment. Henry Charles Beeching argued for an adverbial meaning, such as "surprisingly" or "unexpectedly." George Wyndham glossed it as "not favored in the way a favorite is." Edmond Malone noted the resemblance of lines 5-8 to Henry VIII 3.2.352-8.

Word Choice

The quarto reads "worth" at the end of line nine. Edward Capell proposed the emendation "might," which is comprehensible in terms of typesetting. Lewis Theobald proposed "fight," which is now widely accepted; he also proposed, alternately, that "worth" be retained and 11's "quite" be changed to "forth." John Payne Collier is among the few critics to take this alternative seriously. George Steevens opined that "the quatrain is not worth the labor that has been bestowed on it."

Marigold Metaphor

Edward Dowden notes that the marigold was most commonly mentioned in Renaissance literature as a heliotrope, with the various symbolic associations connected to that type of plant; William James Rolfe finds an analogous reference to the plant in George Wither's poetry.

The marigold is also a metaphor for the subject's pride (as mentioned above in Paraphrase). In the time the sonnet was written, it was understood that the marigold opened with the sun and closed in its absence.. The sun, for the sake of the metaphor, would be the praise the subject is receiving, therefore causing him to "spread his fair leaves," and soak in the fame. As soon as the public stops worshipping him, he will close up, with no admiration to consume (Duncan-Jones).

Interpretations

- David Warner, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakespeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Earl, A.J. (1978). Romeo and Juliet and The Elizabethan Sonnets. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 25 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 25 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png)