Sparrow Hawk (pinnace)

Pinnace Sparrow-Hawk | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Sparrow Hawk |

| In service: | June, 1626 |

| Out of service: | July, 1626 |

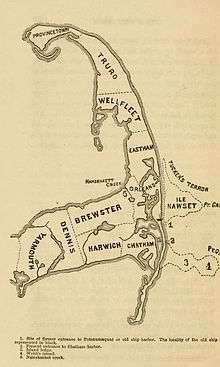

| Struck: | Nauset Beach, Orleans, MA |

| Homeport: | London, England |

| Fate: | wreck |

| Status: | Museum reconstruction. |

| Notes: | Hull reconstruction owned by Pilgrim Society, now on long term loan to Cape Cod Maritime Museum. |

| General characteristics Profile | |

| Type: | pinnace |

| Displacement: | 30 tons |

| Length: | 40 ft (12 m) |

| Beam: | 12.83 ft (3.91 m) |

| Draft: | 9.63 ft (2.94 m) |

| Speed: | ? 2-7 knots |

| Range: | offshore, ocean |

| Complement: | 25 |

| Armament: | None |

| Armour: | None |

| Notes: |

|

The Sparrow-Hawk was a 'small pinnace' similar to the full-rigged pinnace Virginia that sailed for the English Colonies in June 1626. She is notable as the earliest ship known from the first decades of English settlement in the New World to have survived to the present day.

A rough, six week voyage ended in a storm off Orleans, Massachusetts on Cape Cod when the heavily loaded “Sparrow-Hawk” was driven onto the isolated Nauset Beach. All aboard survived and were removed to the nearby Plymouth Colony. Storms and shifting sand buried the wrecked pinnace within several weeks. Sparrow-Hawk remained buried until May, 1863 storms uncovered the hull which was soon salvaged. Keel, planks, rudder and other hull elements from the Sparrow-Hawk were found in good condition, removed from the beach and carefully reconstructed for subsequent exhibition.

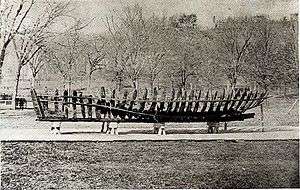

Sparrow-Hawk is important to the history of ship building in England and colonies. Several of the best naval architects of the 1860s in Boston collaborated on a reconstruction which received widespread exhibition during the next few years. Considerable information has been gleaned from the Sparrow Hawk about hull design and construction of the 'small' pinnace design of the early 17th century. She is now on long term loan from the Pilgrim Society to the Cape Cod Maritime Museum in Hyannis, Massachusetts.

Wrecked on Cape Cod

The Sparrow-Hawk left London, June 1626 loaded with passengers for the Jamestown Colony and Virginia. Certainly, she was of a minimum size that any Company would choose to send across the Atlantic with settlers and passengers, many of whom would be unfamiliar with the great ocean and its sometimes violent weather.[1]

After six weeks, the Sparrow-Hawk reached the coast of Massachusetts, and was wrecked at Potanumaquut Harbor Cape Cod. Upon reaching Cape Cod, the Sparrow-Hawk no longer had fresh water or 'beer'. Captain Johnston was in his cabin, sick and lame with scurvy. At night, the Sparrow-Hawk hit a sand bar but the water was smooth and she laid out an anchor. The morning revealed that the caulking between hull planks - Oakum - had been driven out. High winds drove the Sparrow-Hawk over the bar and into the Harbor. Many goods were rescued and no lives were lost.

Two survivors were guided to William Bradford and the Plimouth Plantation by two Indians who spoke English. A shallop with Governor Bradford and supplies to repair the Sparrow-Hawk was sent to rescue the crew. Sparrow-Hawk was repaired and set to sea with cargo. However, yet another violent storm drove her onshore, and render her condition beyond repair. Mariners and passengers removed to the Plimouth Plantation. There, they were housed and fed for nine months before joining two vessels headed down the coast to Virginia. [2][3]

Sparrow-Hawk was buried in the sand and marsh mud of an Orleans, Massachusetts beach that came to be known as “Old Ship Harbor”. Her 'grave' was a low oxygen environment which greatly aided preservation of hull timbers which were described as devoid of worms and barnacles. All metal fastenings had disappeared through oxidation. Her keel and hull timbers were visible from time to time when high winds shifted sand on the beach. Visitors were struck by the long "tail-like" projection from the stern. Although a single fierce storm in this area can move sand to a depth of six feet, it is judged that it took several years for the Sparrow-Hawk to be completely buried. Her burial site retained the name Old Ship Harbor into the late 19th century.[4]

Rediscovery

In 1863, a great storm that occurred between May 4 and May 6 uncovered a great deal of the hull. It was discovered by Solomon Linnell and Alfred Rogers of Orleans. On May 9, Leander Crosby visited the Sparrow-Hawk and removed several artifacts. The rudder was few feet distant from the hull and it was removed, studied and re-assembled. By August 1863, Sparrow-Hawk was once again buried beneath the surface for a few months after which she was exposed once again, and then removed above the high water mark.[4]

Interest in the Sparrow-Hawk wreck was intense because it was immediately understood that this was the earliest ship wreck known from the years during which the New England Colonies were first 'planted'. Controversy immediately erupted as the hull was reconstructed. Keel, hull planks and rudder had been preserved by beach sand for more than two centuries.[5]

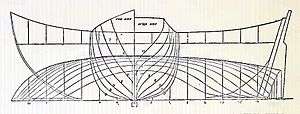

"Considering that even in 1863 the timbers existed only to a height of four feet, one can wonder how Dolliver and Sleeper could have been sure that she had a sheer - the fore-and-aft curve of the deck – of "two and one-half feet, with a lively rise at both ends." Their knowledge of ancient rigging was such that they stated, "The rig common to a vessel of her size at the time she was built consisted of a single mast with a lateen yard and a triangular sail." There is no evidence that English vessels of the early seventeenth century ever carried such a single-masted rig."[6] The English ship of the period whose known dimensions are nearest to those of the Sparrow-Hawk is one built at Rye, East Sussex, England, in 1609. Her keel was 33' long, breadth amidships was 16.5' and depth was 11'. Extrapolating these dimensions to the “Sparrow-Hawk”, reduces her depth to 8'.

Design

As submitted by Dolliver & Sleeper - "Only a practised mechanical eye could detect a little inequality in her sides, in consequence of her having had a heel to port. We have replaced the keel, sternpost, stern-knee, part of the keelson, all the floor timbers, most of the first futtocks and the garboard strake on the starboard side; but the stem and fore-foot, the top timbers and deck are gone. Enough of her, however, remains to enable us to form a fair estimate of her general outline when complete.

The model made by D. J. Lawlor, Esq., embodies our idea of her form and size." . . "Her forward lines are convex, her after lines sharp and concave, and her midship section is almost the arc of a circle. . . "She had a square stern, and no doubt bulwarks as far forward as the waist ; but the outline of the rest of her decks was probably protected by an open rail." Sailing ballast indicated a deeper hull than what was reconstructed, or a ship that was heavily sparred. Grooved floor timbers reveal that timber ropes were present.[7][8][9]

Dennison J. Lawlor was a famous Boston Naval architect who produced a line plan in which the Sparrow-Hawk had two masts. The forward mast carried a single square sail, the mizzen mast (after mast) carried a lateen sail. It was decided by a 'Mr. Sanders' to use Lawlor's plan but reduce the depth to about 8'. Common arcs of circles replaced the sheer line with "lively rise" at both ends. Paintings of small square stern ships of this period show an overhang aft, instead of a flat transom, with an outboard rudder as drawn by Lawlor. Sander's rig takes into account the mast step, and thereby reduced the rig to two possibilities: 'simple' three masted; or the two-masted, square rig known in the 17th century ships as a Barque.[6]

In 1980, Baker summed up the difficulties and potential confusion when assessing a ship as a potential pinnace candidate.[10] There is no consensus as to what type of ship should be assigned to the Sparrow-Hawk. Decked and with a square stern, she cannot be a shallop. Baker believes her too chunky to be a pinnace, others call her a 'ketch' but this author goes with the department of Nautical Archeology at Texas A&M University that assigns “Sparrow-Hawk” to the pinnace category, and representative of the 'small pinnace' design in contrast to the 'large pinnace' type.[11]

Exhibitions

The reconstructed Sparrow-Hawk hull was exhibited in several cities, including on Boston Commons in 1865, and then given to the Pilgrim Society in 1889 and exhibited for over a hundred years at the Pilgrim Hall Museum. The Sparrow-Hawk hull is now on extended loan to the Cape Cod, Maritime Museum on the harborside in Hyannis, Massachusetts.[12] [13][14]

Footnotes

- ↑ For comparison, the Mayflower at 180 tons was one of the larger ships to leave England for the colonies during the early decades of the 17th century although it (the Mayflower) was a relatively averaged size vessel in general 17th century terms. By contrast, the Ark which brought the Maryland Colony in 1634 was 400 tons.

- ↑ Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626 Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W.Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, pp 3-5.

- ↑ An account of the discovery of an ancient ship on the eastern shore of Cape Cod (1864), by Amos Otis, Albany: J.Munsell 1864: pp4-5.

- 1 2 Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626 Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W.Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, pp 27-9. Artifacts found included beef and mutton bones, soles from several shoes, a metallic box and an opium pipe.

- ↑ Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626. Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W. Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, p.28. ".... There were twenty-three regular frames remaining, or forty-six timbers, not counting the six at the stern. At the bow, several frames were missing. The planks were fastened with spikes and treenail, in the same manner as at the present time. Some of the tree-nails had been wedged after they were first driven, showing that some repairs had been made."

- 1 2 Some Seventeenth Century Vessels and the Sparrow-Hawk, by William Avery Baker, Pilgrim Society Note 1(28), 1980, web page May 18, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ↑ Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626. Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W.Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, p.10.

- ↑ Sparrow HawkYe antient wrecke.--1626. Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W.Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, p.10-11. "Her keel is of English elm, twenty-eight feet six inches long, sided eight inches and moulded six; the floor timbers amidships are seven feet one inch long, moulded seven inches and sided six, all of oak hewn square at the corners and fastened through the keel with one-inch oak treenails wedged in both ends. The first futtocks overlap the floor-timbers about two feet, placed alongside of them, forming almost solid work on the turn of the bilge, with a glut or chock below each of them, but they were not fastened together. She has not any navel timbers. We suppose that the joints of the second futtocks overlapped in the same style as those below them. As already stated, her stem and forefoot are gone; but a part of her sternpost, and her stern-knee entire, are left. The stern-post is mortised into the keel, and has been bolted through it and the knee; but the iron has been oxidized long since. Instead of deadwood aft she has seven forked timbers, the longest four feet in the stem, with a natural branch on each side, and six inches square. Some of these were half fayed to the keel, but none of them were fastened. Through these, the planking was treenailed. Part of the keelson is now in its place; it is sided ten inches and moulded eight, and was fastened to the keel with four iron bolts, driven between the floor-timbers (not through them) into the keel.

- ↑ Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626. Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W. Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865, p.11-12. "Her breadth at present, at four feet two inches depth, from the outside of the timbers, is eleven feet six inches, but when planked, as already stated, it was no doubt twelve feet. She had only three strakes of ceiling, all the rest of the timbers were bare; but she had no doubt a stout clamp for her deck-beams to rest upon and partner-beams as a support to her mast. Her planking was two inches thick, of English oak, fastened with oak treenails. Most of the planks are ten inches wide. The keel has been cut to receive the lower edges of the garboards, which had been spiked to it as well as treenailed through the timbers. The starboard garboard strake is now in its place; and this is the only planking we have put on, for the other strakes are somewhat warped. Her outline, however, is perhaps more clearly defined than if she had been planked throughout. It seems to us that after her floor-timbers were laid and planked over, that the other timbers were filled in piece by piece as the planking progressed, which is still a favorite mode of building in some ports of England, and were not jointed together and raised entire before planking. By the appearance of the planks they have been scorched on the inside and then suddenly saturated in water for the purpose of bending them into shape, as a substitute for the modern mode of steaming. The planks and treenails which have not been used by us are preserved with care, and may be seen by those who wish a more minute description of her construction. We suppose she had a heavy plank sheer or covering-board, and that her deck, like her planking, was of English oak. We consider her model superior to that of many vessels of the same size and even larger, which have been recently built in Nova Scotia, and which may be seen in this port every summer."

- ↑ Some Seventeenth-Century Vessels and the Sparrow-Hawk, by William Avery Baker. Pilgrim Society Note, Series One, Number 28, 1980, April 30, 2006, Plymouth Hall Museum, Plymouth Massachusetts. Historical notes about pinnaces and shallops used during the early years of the Plymouth Colony. "The pinnace is perhaps the most confusing of all the early seventeenth-century types of vessels. Pinnace was more of a use than a type name, for almost any vessel could have been a pinnace or tender to a larger one. Generally speaking, pinnaces were lightly built, single-decked, square-sterned vessels suitable for exploring, trading, and light naval duties. On equal lengths pinnaces tended to be narrower than other types. Although primarily sailing vessels, many pinnaces carried sweeps for moving in calms or around harbors. The rigs of pinnaces ranged from the simple single-masted fore-and-aft one of staysail and sprit mainsail to the mizzenmast, and a square sprit-sail under the bowsprit. To confuse matters further, however, open square-sterned pulling boats were called pinnaces at least as early as 1626."

- ↑ Anth318: Nautical Archeology of the Americas Class 14, nd. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Making Waves: Maritime Ventures on Cape Cod", Exhibits and Collections, 135 South Street, Hyannis MA 02601: Cape Cod Maritime Museum, retrieved 2012-02-15

- ↑ Transformations from Farmer to Seafarer: Cape Cod 1639-1739, Cape Cod Maritime Museum, nd. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ Plans for a mid-17th century New England trading vessel”, by Crackers, January 25, 2011, retrieved February 3, 2011. Although the title of this blog thread refers to "Blessing of the Bay", built at Mystick Shipyard, Medford, Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631 for the coastal trade as far south as New Amsterdam, also discussed the scale model of the Sparrow-Hawk for which plans are available from the Pilgrim Hall Museum, thereby insuring as much historical accuracy as possible. This web page also includes a poor quality b&w photograph of a completedSparrow-Hawk model in which a 'chunky' hull design, half deck at the stern and lateen sail are visible.

Bibliography

- Mathew Baker and the Art of the Shipwright (in German). Baker was royal ship builder under Elizabeth I. "His Fragments of Ancient Shipbuilding (1586) is considered a ground breaking work and invaluable for the study of 16th century shipbuilding". Sept.15, 2005. Chapter 3 (pp. 107-165) of Stephen Johnston, Making mathematical practice: gentlemen, practitioners and artisans in Elizabethan England (Ph.D. Cambridge, 1994). See also Mathew Baker.

- Sparrow Hawk Ye antient wrecke.--1626. Loss of the Sparrow-Hawk in 1626, by Charles W. Livermore and Leander Crosby, Alfred Mudge & Son: Boston: 1865.

- An account of the discovery of an ancient ship on the eastern shore of Cape Cod (1864), by Amos Otis, Albany: J.Munsell 1864.

External links

- The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607-1907, by John Robinson and George Francis Dow, Marine Research Society, Salem, Massachusetts: 1922. As compiled from early primary sources, some of which are 17th century manuscripts.

- Sailing Ship Rigs, with good illustrations.

- The Sparrow-Hawk, Pilgrim Hall Museum, May 18, 2005. An introduction to the Museum and the Sparrow-Hawk.

- Some Seventeenth-Century Vessels and the Sparrow-Hawk, by William Avery Baker. Pilgrim Society Note, Series One, Number 28, 1980, April 30, 2006 (Plymouth Hall Museum, Plymouth Massachusetts. Includes historical notes about pinnaces and shallops used during the early years of the Plymouth Colony.