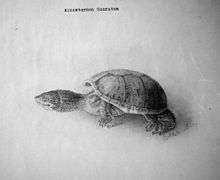

Sternotherus odoratus

| Sternotherus odoratus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Family: | Kinosternidae |

| Subfamily: | Kinosterninae |

| Genus: | Sternotherus |

| Species: | S. odoratus |

| Binomial name | |

| Sternotherus odoratus (Latreille in Sonnini & Latreille, 1801)[2] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Sternotherus odoratus is a species of small turtle native to southeastern Canada and much of the Eastern United States. It is also known as the common musk turtle or stinkpot due to its ability to release a foul musky odor from scent glands on the edge of its shell, possibly to deter predation.[4]

Description

Stinkpots are small black, grey or brown turtles with highly domed shells. They grow to approximately 5.1–14 cm (2.0–5.5 in) and average in weight at 603 g (1.329 lb).[5] They have long necks and rather short legs. The yellow lines on the neck are a good field marker, and often can be seen from above in swimming turtles. Males can usually be distinguished from females by their significantly longer tails and by the spike that protrudes at the end of the tail. The anal vent on the underside of the tail extends out beyond the plastron on males. Females are also typically larger than males. The head is vaguely triangular in shape, with a pointed snout and sharp beak, and yellow-green striping from the tip of the nose to the neck. Barbels are present on the chin and the throat. Their plastrons are relatively small, offering little protection for the legs, and have only one transverse, anterior hinge.[6] Algae often grow on their carapaces. Their tiny tongues are covered in bud-like papillae that allow them to respire underwater.[7]

Behavior

Musk turtles are almost entirely aquatic, spending the vast majority of their time in shallow, heavily vegetated waters of slow moving creeks, or in ponds. They typically only venture onto land when the female lays her eggs, or in some cases, to bask. They can climb sloping, partially submerged tree trunks or branches to as much as 2 m (6.6 ft) above the water surface, and have been known to drop into boats or canoes passing underneath.[6] Their defense mechanism is to excrete a musk scent from a small gland in their underside, hence the name musk turtle. This is used to scare away predators and natural enemies.

Diet

They are carnivorous, consuming a wide variety of aquatic invertebrates including crayfish, freshwater clams, snails, aquatic larvae, tadpoles and various insects. They will also eat fish and carrion. A hatchling's diet is much more carnivorous than an adult's, and may slowly acquire a taste for aquatic plants as the turtle matures. Wild turtles often will not hesitate to bite if harassed. A musk turtle's neck can extend as far as its hind feet; caution is required when handling one.

Habitat

This turtle is found in a variety of wetland habitats and littoral zones, particularly shallow watercourses with a slow current and muddy bottom.[8] Although they are more aquatic than some turtles, they are also capable of climbing, and may be seen basking on fallen trees and woody debris.[9] Fallen trees and coarse woody debris are known to be important components of wetland habitat, and may be particularly beneficial to basking turtles.[10] Like all turtles, they must nest on land, and shoreline real estate development is detrimental. They hibernate buried in the mud under logs, or in muskrat lodges.[11]

Reproduction

Breeding occurs in the spring, and females lay two to 9 elliptical, hard-shelled eggs in a shallow burrow or under shoreline debris. An unusual behavior is the tendency to share nesting sites; in one case there were 16 nests under a single log.[12] The eggs hatch in late summer or early fall. Egg predation is a major cause of mortality, as with many turtle species. In one Pennsylvania population, hatching success was only 15 percent, and predators alone destroyed 25 of 32 nests.[12] Hatchlings are usually less than one inch long and have a very ridged shell which will become less pronounced as they age and will eventually be completely smooth and domed. Their lifespan, as with most turtles, is quite long, with specimens in captivity being recorded at 50+ years of age.

Geographic distribution

The common musk turtle ranges in southern Ontario, southern Quebec, and in the Eastern United States from southern Maine in the north, south through to Florida, and west to central Texas, with a disjunct population located in central Wisconsin.

Taxonomy

The species was first described by the French taxonomist Pierre André Latreille in 1801, from a specimen collected near Charleston, South Carolina. At the time, almost all turtles were classified in the genus Testudo, and he gave it the name Testudo odorata. In 1825, John Edward Gray created the genus Sternotherus to include species of musk turtle and it became Sternotherus odoratus. The species has been redescribed numerous times by many authors, leading to a large amount of confusion in its classification. To confuse it further, the differences between mud turtles and musk turtles are a point of debate, with some researchers considering them the same genus, Kinosternon.

Conservation

Though the common musk turtle holds no federal conservation status in the US and is quite common throughout most of its range, it has declined notably in some ares, and appears to be more sensitive than some native species to human degradation of wetlands.[13] It is listed as a threatened species in the state of Iowa. It is listed as a species at risk in Canada, and is protected by the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).[14] It is also protected under Ontario's endangered species act.[15] In this part of its range, only wetlands with minimal human impact have robust populations.[13] Road mortality of breeding females may be one of the problems associated with human development.

In captivity

Due to its small size, the common musk turtle generally makes a better choice for a pet turtle than other commonly available species, such as the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). Throughout their range, wild-caught specimens are commonly available, but the species is also frequently captive-bred specifically for the pet trade. (In the United States, USDA regulations ban the sale of turtles under four inches long as pets. This technically excludes all musk turtles.) They readily accept a diet of commercially available turtle pellets, algae wafers, and various insects, such as crickets, snails, mealworms, bloodworms, earthworms. A varied diet is essential to a captive turtle's health and it is important to note that it should not be fed with turtle pellets only. A captive turtle being fed a high protein diet may develop vitamin A and E deficiencies. Supplemental calcium in the form of commercial powders or a cuttle bone is also a must. Aquatic plants (water lettuce, duckweed, etc.) can also be provided, as some musk turtles prefer more vegetables in their diet than others. Though less sensitive to limited access to UV lighting, common musk turtles require ultraviolet (UVA and UVB) lighting as most other turtle species do for proper captive care. As bottom dwellers, musk turtles are rarely seen basking, but a basking area should still be provided.

References

- ↑ P. P. van Dijk (2011). "Sternotherus odoratus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ↑ ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System). www.itis.gov.

- ↑ Fritz & Havaš (2007)

- ↑ Ernst et al. (1994), p. 148.

- ↑ "Virginia Turtles – Average Adult Sizes, Virginia Size Records & Overall Size Records" (PDF). Virginia Herpetological Society. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- 1 2 Conant (1975)

- ↑ Matt Walker (May 20, 2010). "Turtle 'super tongue' lets reptile survive underwater". BBC News. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Ernst et al. (1994), pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Ernst et al. (1994), p. 142.

- ↑ Keddy (2010), p. 229.

- ↑ Ernst et al. (1994), p. 143.

- 1 2 Ernst et al. (1994), p. 146.

- 1 2 DeCatanzaro & Chow-Fraser (2010)

- ↑ "Eastern Musk Turtle". Species at Risk Register. Government of Canada. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Eastern Musk Turtle". Ontario's Biodiversity: Species at Risk. Royal Ontario Museum. September 2009.

Bibliography

- Roger Conant (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America (Second ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-19977-8.

- Rachel DeCatanzaro & Patricia Chow-Fraser (2010). "Relationship of road density and marsh condition to turtle assemblage characteristics in the Laurentian Great Lakes". Journal of Great Lakes Research. 36 (2): 357–365. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2010.02.003.

- Carl H. Ernst; Jeffrey E. Lovich; Roger William Barbour (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-346-0.

- Uwe Fritz & Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 263–264. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 17, 2010.

- Paul A. Keddy (2010). Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78367-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sternotherus odoratus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Sternotherus odoratus |

- Tortoise Trust: Common Musk Turtle

- Eastern Musk Turtle, Ontario Nature

- The Center for Reptile & Amphibian Conservation: Common Musk Turtle

- eNature.com Nature Guides: Common Musk Turtle

- Sternotherus odoratus in Connecticut