Sydney punchbowls

The Sydney punchbowls, made in China during Emperor Chia Ch'ing's reign in 1796–1820, are the only two known examples of Chinese export porcelain hand painted with Sydney scenes and dating from the Macquarie era. The bowls were procured in Canton about three decades after the First Fleet's arrival at Port Jackson where the British settlement at Sydney Cove was established in 1788. They also represent the trading between Australia and China via India at the time. Even though decorated punchbowls were prestigious items used for drinking punch at social gatherings during the 18th and 19th centuries, it is not known who originally commissioned these bowls or what special occasion they were made for.

The punchbowls are a 'harlequin pair', similar but not exactly matching. The bowls have been donated independently, one to the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW) in 1926 and the other to the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) in 2006. The Library bowl is the more widely known of the pair. Its earliest provenance places it in England in the late 1840s, where it is said to originally have been commissioned for William Bligh; another source suggests Henry Colden Antill. It passed through several owners in Britain before it was presented to the State Library. The Museum bowl's first provenance is from England in 1932 and it has been suggested that it was made to the order of Arthur Phillip. Its whereabouts were unknown until it appeared in the Newark Museum, United States, in 1988, on loan from Peter Frelinghuysen Jr.. Through donations, the Maritime Museum later acquired the punchbowl from Frelinghuysen.

The punchbowls are of polychrome famille rose with gilding, adorned with panoramic views from opposite vantage points of early 19th century Sydney, combined with traditional Chinese porcelain decorations and each features a rare, lively tondo grouping of Aboriginal figures. The panoramas are detailed and show a number of landmarks in and around Sidney Cove at the time. The motifs have probably been taken from artwork by several artists working in Australia during the 18th and early 19th century.

History

Background

Hand painted Chinese porcelain dinner wares became the height of fashion in Europe and North America during the 18th century as a way showing off wealth and status in society.[1] The porcelain was ordered through different East India Companies and later independent American traders;[2] all Western trading companies with ships sailing to China.[2] The porcelain was decorated with a combination of Chinese patterns and Western motifs selected by its commissioner. The Chinese manufacturers sent porcelain samples of decorations to their prospective clients in Europe and the United States and their clients provided the porcelain painters in China with paintings, drawings or sketches for their orders.[3] These dinner wares are categorized into familles (French for "families") mainly by the colors they are painted in such as famille verte, noire, jaune and rose.[4]

These sets of tableware included all the dishes necessary to set a grand table for a gala dinner. A 1766 order form from the Swedish East India Company stated that "small services" contained 224 pieces and a "larger service" 281 pieces.[5] Punchbowls however, were not included in these sets, they were ordered separately as showcase pieces. The bowls were used to serve hot or cold drinks at special occasions in clubs, at social gatherings and in wealthy homes, or before or after grand dinners.[6][7]

After the British settlement at Sydney Cove was established in 1788,[8] a significant part of the Chinese porcelain shipped to Australia came via British traders living in India.[1] Operating under licences issued by the British East India Company, who held a commercial monopoly in the Far East, this trade was known as the 'Country Trade', the Indian ships were called 'Country Ships' and their captains 'Country Captains'.[9] Examination of the cargo of ships wrecked during the early colonisation of Australia[10] show that the Country Trade played an important role in getting supplies, including Chinese porcelain traded via India often in Indian-built vessels, to the early Australian colonies.[11]

The two Sydney punchbowls are the only known examples of Chinese export porcelain hand painted with Sydney scenes and dating from the Macquarie era,[12] lasting 1810–1821.[13] The bowls were procured in China sometime between 1796 and 1820;[14] about three decades after the First Fleet's arrival at Port Jackson in Sydney Cove.[8] By 1850 Chinese-made porcelain imports had been replaced with British earthenwares transfer-printed with decoration of Chinese derivation.[15]

Function

Whilst the drinking of punch from punchbowls was an actual social practice of the times, the Sydney Cove punchbowls were specially commissioned and expensive items which had other purposes.[16] Such punchbowls were prestigious items owned by individuals of high rank in society, such as John Hosking Sydney's first elected Mayor,[17] and New York's fourth Governor Daniel Tomkins, who also acquired a punchbowl.[18] The two punchbowls, previously owned by Hosking, are the first Chinese objects acquired by the Australiana Fund.[19] The bowls could also have been commissioned as commemorative gifts, like the 1812 Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania Union Lodge punchbowl gift.[20][21] and the New York City punchbowl presented to the City of New York on 4 July 1812.[22][23] It has also been suggested that, given the Aboriginal marriage motif, the Sydney punchbowls may have been a marriage gift.[24] Punchbowls were also regarded as exotic souvenirs at the time.[7]

It is also possible the Sydney punchbowls may have had other purposes – to promote the fledgling settlement and to encourage new settlers. In 1820, artist John William Lewin's patron, merchant Alexander Riley, looking for ways to promote the New South Wales colony, stated: "It has long been a subject of our consideration in this Country that a Panorama exhibited in London of the Town of Sydney and surrounding scenery would create much public interest and ultimately be of service to the Colony".[25] This purpose is clearly set forth even in the title of William Charles Wentworth's tome on New South Wales, which contained the engraving of Lewin's Sydney Cove painting. The full title ends "... With a Particular Enumeration of the Advantages Which These Colonies Offer for Emigration, and Their Superiority in Many Respects Over Those Possessed by the United States of America".[26] The punchbowls were also an opportunity to present the art of topographical panoramas in the form of a high status object and to portray the new colony in a more glamorous way than that of simply a remote convict colony as perceived at the time.[27]

Commissioning

The gilded monogram initials on the Library punchbowl are perhaps the only current clue as to the original commissioner of the punchbowls. The initials are difficult to decipher because of partial loss of the gilt Copperplate script. Possibilities include HCA or HA, TCA or FCA over B. Several candidates have been suggested including Henry, 3rd Earl of Bathurst, and Sir Thomas Brisbane, New South Wales Governor in 1821–1825 after Lachlan Macquarie, but the most likely is Henry Colden Antill (1779–1852).[28] Antill was appointed aide-de-camp to the fifth New South Wales Governor, Macquarie who was in office 1810–1821, on his arrival in Sydney on 1 January 1810.[29] He was promoted to Major of Brigade in 1811 and retired from the British Army in 1821. Antill settled on land first at Moorebank near Liverpool and then in 1825 on his estate near Picton—named Jarvisfield[30] in honour of Macquarie's first wife, Jane Jarvis.[31] He was buried at Jarvisfield on 14 August 1851. Antill had subdivided part of the estate in 1844, making possible the founding of the town of Picton.[32] When the State Library acquired its punchbowl in 1926, the Antill family[33] of Picton[34] — Henry's antecedents — had no knowledge of the punchbowl's provenance.[14]

20th-century provenance

The Library punchbowl

The State Library's punchbowl was the earlier of the two to become more widely known. It was presented to the Library by Sydney antiques dealer, auctioneer and collector, William Augustus Little, in November 1926, an event reported in the Sydney Evening News on 3 November 1926. The punchbowl discovery itself was reported in several Australian newspapers earlier in March, including the The Sydney Morning Herald on 4 March 1926, with the title Bookshop Find : Relic of Early Sydney.[35] These newspaper articles state that Little bought the punchbowl from London antiquarian bookseller, Francis Edwards Ltd[36] of 83 Marylebone High Street and that Little subsequently had it appraised by experts from the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in February 1926. The newspapers report that the V&A wished to keep the bowl. The articles also state that the bowl had "paintings of Sydney in 1810, executed to the order of Major Antill who was Governor Macquarie's aide-de-camp". Among the clientele of Francis Edwards Ltd were some of the noted Australiana collectors of the day, including William Dixon, James Edge-Partington, David Scott Mitchell and the Mitchell Library itself.[24][37]

Before Little's purchase, the punchbowl had been the property of Sir Timothy Augustine Coghlan, New South Wales Agent-General in London, who bought the bowl for ₤40 in 1923 from one Miss Hall for his own collection. The bowl was subsequently in the possession of Francis Edwards Ltd before Coghlan's unexpected death in London on 30 April 1926. Coghlan had personally collected the bowl from a Miss Hall at 'Highfield', 63 Seabrook Rd, Hythe (Kent), England, a few months after she had decided to offer the bowl to the New South Wales Government for ₤50. Earlier, a visit to Miss Hall by a Sydney schoolteacher, Jessie Stead, on 6 August 1923, resulted in the proposal that the bowl ought to be the property of the City of Sydney. Jessie Stead later indicated that she was informed by Miss Hall that her father had acquired the bowl in the late 1840s – the earliest dating for the punchbowls' provenance – and that Miss Hall believed the bowl was commissioned for William Bligh, New South Wales's fourth Governor (in office 1806–1808).[24] In 2002, the State Library of New South Wales digitised the punchbowl images[38] with the support of the Nelson Meers Foundation, a philanthropic foundation supporting Australian arts,[39] and the bowl became one of the 100 extraordinary library objects[40] to be exhibited as part of Mitchell Library's centenary celebrations in 2010.[41]

The Museum punchbowl

The second Sydney punchbowl had a much more circuitous journey to the present. The bowl first appeared in May 1932, when Sir Robert Witt, chairman of the British National Art Collections Fund, wrote to James MacDonald, Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, inquiring if a Sydney museum would be interested in acquiring the second punchbowl. The Gallery Director referred the offer to William Herbert Ifould,[42] Principal Librarian of the Public Library of New South Wales, in August 1932. Ifould wrote directly to Sir Robert Witt indicating that the bowl was not required by the Library as a very similar one was already held. Ifould received a reply dated 31 October 1932, stating that during the intervening months the owner of the bowl in England – whose name was undisclosed – had since sold the bowl to another undisclosed buyer. The bowl's subsequent whereabouts was unknown until 1988.[24] In the original offer by Sir Robert – who had also co-founded the Courtauld Institute of Art in London – a suggestion was made that this bowl had been made to the order of Arthur Phillip, the first Governor of New South Wales (in office 1788–1795) who established the settlement at Sydney Cove. However, no evidence to support this view was given in Witt's letter.[14]

1988 was the bicentenary of non-indigenous settlement in Australia and, as such, there was renewed interest in the 'lost' second Sydney punchbowl. The bowl eventually turned up in a catalogue for a Chinese export porcelain exhibition at Newark Museum, New Jersey, United States,[43] titled Chinese Export Porcelain: A Loan Exhibition from New Jersey Collections. The bowl had been lent by Peter Frelinghuysen Jr., a former United States Congressman (in office 1953–1975).[44] The discovery was made by Terry Ingram, a Sydney journalist specialising in antiques and art, who wrote about it in his Saleroom column, titled Newark Museum packs Aussie punch, in The Australian Financial Review on 25 August 1988.[45] It transpired that in the early 1930s, the bowl was acquired by Frelinghuysen's parents in a private negotiation with the owner at the time the National Art Collections Fund was attempting to raise interest from Sydney's cultural institutions. This discovery drew the attention of Paul Hundley, senior curator of the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM)'s USA Gallery, the Gallery itself a bicentennial gift of the American people to Australia. In May 2006, the ANMM announced it had acquired the bowl as a part gift from Frelinghuysen through the American Friends of the ANMM, a charitable organisation recognised by the US Internal Revenue Service which enabled Frelinghuysen to receive appropriate taxation benefits.[46][47] The Australian Financial Review reported the acquisition in its Saleroom column, titled Museum bowled over, on 18 May 2006.[48] The punchbowl has been on display in the Museum's USA Gallery ever since. It also features as one of the 100 Stories from the ANMM,[49] has digitised images in the ANMM catalogue[50] and can be viewed on YouTube.[51] At the time the ANMM acquired the punchbowl in 2006, the bowl was valued at $A330,000.[52]

Ceramic origin

The notes accompanying the State Library's acquisition of its punchbowl indicate that on 25 February 1926, William Bowyer Honey, Keeper, Department of Ceramics, Victoria & Albert Museum, had appraised this particular punchbowl. Honey concluded that the bowl was made in China during Emperor Chia Ch'ing's reign in 1796–1820.[14] In 1757, foreign trade had been restricted to Canton. Chinese exports, consisting largely of tea, porcelain and silk, had to be paid for in silver. The European (and soon the American) presence was restricted to the Thirteen Factories known as hongs on the harbour of Canton (now known as Guangzhou). The Canton hongs themselves are frequently illustrated on punchbowls, known as hong bowls,[53] whereas the portrayal of ports that traded with Canton – such as Sydney and New York – are extraordinarily rare.[54] The Canton System lasted until the defeat of China's Qing dynasty by the British Empire in the first of the Opium Wars in 1842.[55][2][56] Virtually no Chinese export porcelain was produced from 1839 to 1860 because of the Opium Wars.[57][58] Canton hong trade was subsequently overshadowed by the rise of Hong Kong as a trading centre – territory ceded to the British as a consequence of China's military defeats – and the subsequent establishment of 80 Treaty ports along China's coast.[59] The punchbowls therefore are a product made just before China's eclipse, commissioned in Canton, where they were painted and glazed by Chinese ceramic artists. The unpainted bowls, however, would have first been manufactured in Jingdezhan, a town 800 km (500 mi) by road from Canton, where pottery factories have operated for nearly 2,000 years, and still do today.[24]

Similarities and differences

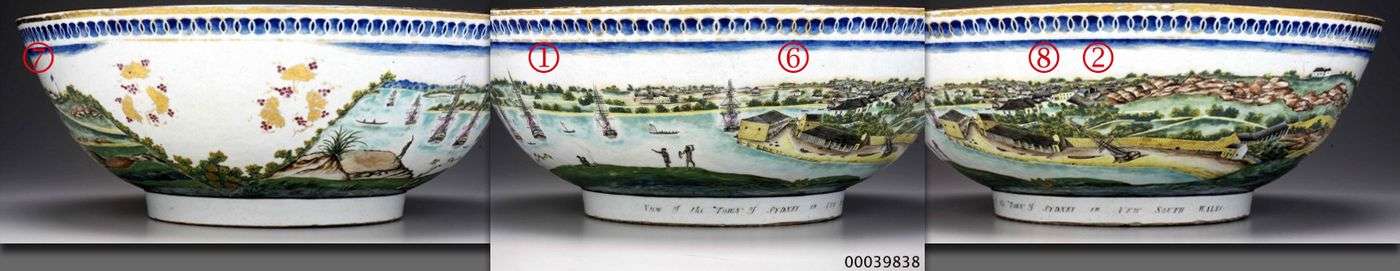

The punchbowls can be considered a harlequin pair as they are similar but not exactly matching. They are both Chinese ceramics ware of Cantonese origin, made of clear glaze on hard-paste porcelain and painted with polychrome famille rose[60][61] overglaze enamel and gilding.[62] They are similar in size, each approximately 45 cm (18 in) in diameter, 17 cm (6.7 in) high and weighing about 5.4 kg (12 lb), footring 2.5 cm (1 in) high and 22.5 cm (8.9 in) in diameter.[62] Whilst the indigenous Australian groups painted within the inner centre of both bowls are identical, the outer panoramic views of Sydney Cove are not. The Library punchbowl has a view from the eastern side of Sydney Cove whilst the view on the Museum bowl is from Dawes Point on the western shore. This pairing follows a standard convention in late 18th-and early 19th-century topographical art of painting two views of the same scene from opposite vantage points.[24]

Whilst the Cantonese ceramic painters would have worked from images of Sydney Cove and the Aboriginal group provided by the customer commissioning the punchbowls, the border and edge trims were generally left to the choice of the ceramic painters.[24] The traditional floral motif of such Chinese flowers as chrysanthemums, peonies, cherry and plum blossom has been applied to the internal borders of both bowls in a similar pattern. However, the external borders differ considerably. The Library bowl has a more traditional Chinese outer border design in vermilion, rose and gilt,[62] whilst the Museum bowl has a trim of looped circles on a cobalt blue ground, edged with narrow gold bands.[50] There are other differences. The Library bowl has large, gilded monogram initials on the outside and the footring has a single narrow gold band and gilded lower edge.[62] However, the Museum bowl has no visible monogram but the footring does have "View of the Town of Sydney in New South Wales" lettered in black.[50]

Illustration sources

Sydney Cove

The sources of the two illustrations of Sydney Cove and the Aboriginal group are not known. The ceramic colouring bears a general resemblance to contemporary Sydney Cove images which implies that an original watercolour or hand coloured engraving was used for copying rather than black and white images.[28] In the case of the Library punchbowl, the depiction of Sydney Cove is most likely done from an engraving after a now lost drawing by Lewin,[63] which may date to 1814.[64] This Sydney Cove engraving appeared as a full-page illustration in the second edition of A Statistical, Historical and Political Description of New South Wales and its dependent settlements in Van Diemen's Land etc[65] (London, 1820) by Wentworth, with a later, smaller, version as one of ten Port Jackson harbour views illustrated on Map of Part of New South Wales[66] (London, 1825) by publisher and engraver, Joseph Cross.[67] As Australia's first professional artist, Lewin produced many paintings for Macquarie and his senior officers. He also made a number of commissions for Riley. Lewin had a close association with Antill[62] and both were part of Governor Macquarie's 50-strong excursion party to inspect land and the new road over the Blue Mountains from 25 April to 19 May 1815.[68] The road had been built by convicts in 1814,[69] after the first European crossing by Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and Wentworth in May 1813.[70]

Unlike the Library punchbowl, the Sydney Cove image on the Museum punchbowl is not known in its entirety in any other version so it is assumed that the original artwork provided by the commissioner to the ceramic artists in China has been lost. The only similar Sydney Cove view of the period is an original watercolour by convict artist Joseph Lycett,[71] which first appeared in an engraved version as page 86 in Views in New South Wales, 1813–1814 [and] An Historical Account of the Colony of NSW, 1820–1821[72] (Sydney, 1819) by soldier, James Wallis.[73] A second engraved version appeared on page 74 of a similar folio edition Album of original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett, ca 1817–1818 etc[74] by publisher Rudolph Ackermann in London, 1821. However, the Dawes Point fortifications — designed by the convict architect Francis Greenway — and its gun emplacements, dominate the foreground of both engravings. The Museum punchbowl view pre-dates this as it has, instead, a grassy slope and figures of an Aboriginal man and woman in the equivalent location. The Lycett version has other major differences, including a less extensive vista of the eastern side of the Harbour.[24]

Aboriginal group

The Aboriginal group forms the inner centre piece in the tondo of both bowls. As the same image was used for both bowls, the implication is that the Chinese ceramic painters were copying from the same drawing and finishing them at the same place and time. The image is of a group of four Aboriginal men with club, shield and spears, one woman with a baby on her shoulders – standing and turned slightly away from the rest of the figures – and another woman cowed by the men. This is thought to depict a preliminary marriage ceremony.[75] As with the Museum bowl's Sydney Cove image, no directly related, surviving, version is known that would have been used by the ceramic artists to paint the Aboriginal group. The closest match is a drawing after an apparently now-lost original sketch by Nicolas-Martin Petit,[76] artist on the 1800–1803 French expedition to Australia led by Nicolas Baudin.[24] Research made around 2009–2012,[77][78] indicated that during Baudin's expedition, a report was prepared for Emperor Napoleon on the feasibility of capturing the British colony at Sydney Cove.[77][79] As this expedition progressed around coastal Australia, Petit began to specialise in the drawing of portraits of indigenous peoples.[76] The French expedition arrived at Port Jackson on 25 April 1802.[80] Petit's drawing was copied for publication as plate 114 in the Voyage autour du monde : entrepris par ordre du roi (Paris, 1825) ,[81] regarding a voyage around the world (1817–1820) led by Louis-Claude de Saulces de Freycinet.[24] The engraving is entitled Port Jackson, Nlle Hollande. Ceremonie preliminaire d'un mariage, chez les sauvages[82] (ceremony before a marriage among the natives, Port Jackson, New Holland). Port Jackson aborigines are from the Eora group of indigenous people living in the Sydney Basin.[83]

Sydney Cove panoramas

The Library punchbowl

.pdf.jpg)

The panorama on the Library punchbowl begins with a view of the eastern shore of Sydney Cove.[84] In the foreground is an octagonal two-storey, yellow, sandstone house ①, built by Governor Macquarie in 1812 for his favourite boatman and former water bailiff, Billy or William Blue. The drawing of this little house – now the site of the Sydney Opera House — is out of all proportion to its actual modest size. To the left of the house is a sandy beach where the Circular Quay ferry wharves now stand. Facing the beach is First Government House ② where the Museum of Sydney is now situated.[62]

On the western shore is the Rocks district, the convicts' side of the town, with two windmills on the ridge. The buildings were simple vernacular houses. Newly arrived convicts often found lodging in the district and in the 1790s a large number of the inhabitants were also Aborigines.[85] To the left of The Rocks area is a long, low, military barracks ③, built between 1792 and 1818 around Barracks Square/the Parade Ground – which is now Wynyard Park.[86] It was from here that, in 1808, the New South Wales Corps marched to arrest Macquarie's predecessor William Bligh, an event later known as the Rum Rebellion. Heading east is St. Philip's Church ④ – the earliest Christian church (Church of England) in Australia – erected in stone in 1810 on Church Hill – now Lang Park.[87] In 1798, the original wattle and daub church – on what is now the corner of Bligh and Hunter Streets – was burnt down, allegedly by disgruntled convicts in response to a decree by the second New South Wales Governor (1795–1800), John Hunter, that all colony residents, including officers and convicts, attend Sunday services.[88] The jail had earlier suffered a similar fate.[89]

Further along the ridge to the east is Fort Phillip, flying the Union Jack, on Windmill (later Observatory) Hill where the Sydney Observatory is now located. It was the highest point above the colony, affording commanding views of the Harbour approaches from east and west.[90][91] On the waterfront below Fort Phillip is the yellow, four-storey, Commissariat Stores, ⑤,[92] constructed by convicts for Macquarie in 1810 and 1812. One of the largest buildings constructed in the colony at the time, it is now the site of the Museum of Contemporary Art. The foreshore buildings on the extreme right are the warehouse and "Wharf House" residence of merchant, Robert Campbell ⑥ who was to become one of the colony's biggest landholders.[93][94] This is now the site of the Sydney Harbour Bridge pylons and is just to the left of Dawes Point.[95] Three British sailing ships, flying either the Red Ensign of the Merchant Navy or (more likely) the White Ensign of the Royal Navy, are anchored in the Cove[24] along with four sailboats and five canoes.[38]

The Museum punchbowl

The Sydney Cove panorama on the Museum punchbowl is dated between 1812 and 1818. The vantage point is from beneath Dawes Point, shown with its flagstaff and before the Dawes Point fortifications built 1818–1821 ⑦. Looking directly into Campbell's Cove, the immediate focal points are Robert Campbell's warehouse and the "Wharf House" roof of his residence ⑥. To the right of Campbell's Wharf are extensive stone walls marking boundaries between properties in this part of the Rocks district ⑧. First Government House can be seen at the head of Sydney Cove in the distance ② and around the eastern shore a small rendition of Billy Blue's 1812-house ①. The Governor and civil personnel lived on the more orderly eastern slopes of the Tank Stream, compared to the disorderly western side where convicts lived. The Tank Stream was the fresh water course emptying into Sydney Cove and supplied the fledgling colony until 1826. Further along is Bennelong Point – with no sign of Fort Macquarie[96] built from December 1817 – and Garden Island – the colony's first food source. The distant vista of the eastern side of the Harbour goes almost as far as the Macquarie Lighthouse – Australia's first lighthouse – built between 1816 and 1818 on South Head.[24] There are seven sailing ships flying the white ensign of the British Royal Navy in the Harbour, along with three sailboats and two canoes.[50]

References

- 1 2 Staniforth, Mark (1996). "Tracing artefact trajectories — following Chinese export porcelain" (PDF). Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology. 20 (1).

- 1 2 3 "Canton: Common and Unusual Views". Antiques and Fine Art Magazine. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Kjellberg 1975, pp. 241–245.

- ↑ Kjellberg 1975, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Kjellberg 1975, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ "Chinese Export Porcelain Punch Bowl". Albany Institute of History & Art. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Hong bowl". www.si.edu. Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 "The First Fleet". www.gutenberg.net.au. Project Gutenberg Australia. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "COUNTRY-CAPTAIN to COWLE". www.bibliomania.com. The Hobson Jobson Dictionary. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Staniforth, Mark (2009) 'Shipwreck cargoes: approaches to material culture in Australian maritime archaeology'. Historical Archaeology 43(3):95–100.

- ↑ Nash, Michael (2002). "The Sydney Cove shipwreck project". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (31): 39–59. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2002.tb01399.x.

- ↑ "The Macquarie era". www2.sl.nsw.gov.au. State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive (LEMA) Project". Macquarie University. 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Notes on the Chinese Porcelain Bowl(XR10)". File Ap 64, Manuscript Note, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

- ↑ Stanbury, Myra 2003 The Barque Eglinton: Wrecked Western Australia 1852. Special Publication 13, Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology, Fremantle, WA.

- ↑ "Around the punchbowl". Sydney Living Museums. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Parsons, Vivienne (1966). "Hosking, John (1806–1882)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese Export Porcelain Punch Bowl". Albany Institute of History & Art. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Pair of (Hosking) punch bowls, C.1829". Australian Historical Art Fund & Heritage Government Residences. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "1812 Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania Union Lodge punchbowl". Phoenixmasonry Masonic Museum and Library. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese export porcelain Masonic Punchbowl". Cohen and Cohen. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "New York's old Punch Bowl: has received many nicks during the Century". Los Angeles Times. 17 November 1912. p. 16.

- ↑ Le Corbeiller & Cooney Frelinghuysen 2003, pp. 50–51.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ellis 2012, pp. 18–30.

- ↑ "Alexander Riley to Edward Riley, Riley Papers, A 110, in Alexander Riley – papers, 1804–1838 in Manuscripts,Oral History and Pictures Catalogue". State Library of New South Wales. p. 15.

- ↑ Wentworth, W.C. (2003). "Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of The Colony of New South Wales etc." (PDF). University of Sydney Library. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Cumming 2006, pp. 1–3.

- 1 2 Ellis 2012, p. 23.

- ↑ "Henry Colden Antill". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "The History of Jarvisfield". Jarvisfield Estate. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Macquarie (née Jarvis) [1772–1796], Jane. "The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive". Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Antill, J. M. (1966). "Antill, Henry Colden (1779–1852)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ "Jihn MacQuarie Antill, Maj.-General & Thomas Horan, postmaster". Australian Postal History & Social Philately. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ Vincent, Liz (20 March 2006). "Picton — the early years". Internet Family History Association of Australia Local History Library. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bookshop Find: Relic of Early Sydney". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 March 1926. p. 11.

- ↑ "Antiquarian Booksellers since 1855: The Company". Francis Edwards. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "David Mitchell, the Mitchell Library and Australiana". Government of Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Chinese export ware punchbowl featuring a scene of Sydney Cove before 1820: manuscripts catalogue". State Library of New South Wales.

- ↑ "About Nelson Meers Foundation". Nelson Meers Foundation. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Number 29 of the 100 extraordinary library objects : Mitchell Library Centenary Exhibition". Government of New South Wales. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "Mitchell Library Centenary Exhibition". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Arnot, Jean F. "Ifould, William Herbert (1877–1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Darrow, Carolyn (14 October 1979). "Focus on Orient in Newark Show". The New York Times. p. 21.

- ↑ "Christies Press Release : Exceptional collection of Chinese Export Porcelain from late U.S. Congressman Peter H. B. Frelinghuysen, JR.". Christie's. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Ingram, Terry (25 August 1988). "Saleroom:Newark Museum packs Aussie punch". The Australian Financial Review. p. 40.

- ↑ "American Friends of the ANMM". Australian National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Hundley, Paul (September–November 2006). "Collections : Precious Porcelain" (PDF). Signals (76). Australian National Maritime Museum. pp. 40–41. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Strickland, Katrina (18 May 2006). "Saleroom column: Museum bowled over". The Australian Financial Review. p. 45.

- ↑ "100 Stories from the Australian National Maritime Museum". Australian National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Digitised punchbowl images in the ANMM catalogue". Australian National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "Precious Porcelain". YouTube. Australian National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "Australia : National Maritime Museum acquires valuable 'early Sydney' punch bowl" (PDF). ICMM NEWS. International Congress of Maritime Museums. 28 (2): 6. 2006.

- ↑ "What is a hong bowl?". Quezi. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Massive chinese export punchbowl for American market with view of New York". MasterArt. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Pletcher, Kenneth (17 April 2015). "Opium Wars". www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Perdue, Peter C. "Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System – 1, China in the World (1700-1860s)". www.ocw.mit.edu. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Visualizing Cultures. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ Overstreet Allen, Lorena (1998). "Chinese Canton Porcelain". Antiques & Art Around Florida. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "History of Canton". Canton China Virtual Museum. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ↑ Perdue, Peter C. (2009). "Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System l : China in the world (1700–1860s)" (PDF). Visualizing Cultures. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 1–26. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Feller, John Quentin in Magazine Antiques (October 1983). "Canton famille rose porcelain". 124 (4): 748.

- ↑ Feller, John Quentin in Magazine Antiques (October 1986). "Canton famille rose porcelain". 130 (4): 722–731.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Chinese export ware punchbowl featuring a scene of Sydney Cove before 1820, Manuscripts, Oral History, and Pictures Catalogue". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "About John Lewin: Wild Art". State Library of New South Wales. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ McCormick 1987, pp. 178-9.

- ↑ Wentworth, W. C. (1820). A Statistical, Historical and Political Description of New South Wales etc (e-book ed.). London: Open Library.

- ↑ "Digitised image of Map of Part of New South Wales in Manuscripts catalogue". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "Joseph Cross, engraver". London Street Views. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Macquarie's Crossing". State Library of New South Wales. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Martin, David. "Cox builds the first road, 1814". www.infobluemountains.net.au. Info Blue Mountains. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "History in Detail". www.bluemts.com.au. Blue mountains Australia. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "Joseph Lycett". State Library of New South Wales. 30 April 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Wallis & Oxley 1821, p. 86.

- ↑ Blunden, T. W. (1967). "Wallis, James (1785–1858)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Wallis & Lycett 1821, p. 74.

- ↑ "Marriage in Traditional Aboriginal Societies". Australian Law Reform Commission. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 Petit, Nicolas-Martin. "The Naturalists". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- 1 2 Connor, Michael (November 2009). "History — The secret plan to invade Sydney". Quadrant Online. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "French invasion plan published in new study". www.adelaide.edu.au. University of Adelaide. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Bennett, Bruce (2011). "Exploration or Espionage? Flinders and the French" (PDF). The Journal of the European Association of Studies on Australia. University of Barcelona. 2 (1).

- ↑ "The Baudin Legacy Project, The Voyage". University of Sydney. 10 March 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ de Freycinet 1823, p. (plate) 114.

- ↑ "Port Jackson, Nouvelle Hollande. Ceremonie preliminaire d'un mariage, chez les sauvages: The Freycinet Collection". London: Christie's. 26 September 2002. SALE 6694. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Aboriginal history: The first Sydneysiders". www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au. City of Sydney. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "Sydney Cove West Archaeological Precinct". New South Wales Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ Grace, Karskens (2008). "The Rocks". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ Whitaker, Anne-Maree (2008). "Wynyard Park". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Images : The Rocks : parish Church of St. Philip". Sydney Architecture. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Places of Worship". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ Ramsland, John (2011). "Prisons to 1920". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ "Fort Phillip, Observatory Hill, Sydney". Powerhouse Museum Collection Search. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Dunn, Mark (2008). "Fort Phillip". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Dictionary of Sydney staff writer (2008). "Commissariat Stores". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Steven, Margaret (1966). "Campbell, Robert (1769–1846)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Robert Campbell papers, 1829–1861 in Manuscripts, Oral History and Pictures Catalogue". State Library of New South Wales.

- ↑ Cumming 2006, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ "Journeys in Time: Fort Macquarie". Macquarie University. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Cumming, Helen, ed. (2006). An Unbroken View: Early Nineteenth-century Panoramas, exhibition catalogue (PDF). Sydney: State Library of New South Wales. ISBN 0-7313-7166-6.

- de Freycinet, Louis (1823). Voyage autour du monde : entrepris par ordre du roi ... exécuté sur les corvettes de S.M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820 (Digitised version ed.). State Library of New South Wales.

- Ellis, Elizabeth (2012). "Chinese puzzles: The Sydney punchbowls". Australiana. 34 (2 May).

- Kjellberg, Sven T. (1975). Svenska ostindiska compagnierna 1731–1813: kryddor, te, porslin, siden [The Swedish East India company 1731–1813: spice, tea, porcelain, silk] (in Swedish) (2 ed.). Malmö: Allhem. ISBN 91-7004-058-3. LIBRIS 107047.

- Le Corbeiller, Clare; Cooney Frelinghuysen, Alice (2003). "Chinese Export Porcelain, New York City punchbowl". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 60 (3): 1. doi:10.2307/3269266. JSTOR 3269266.

- McCormick, Tim (1987). First views of Australia, 1788–1825: A history of early Sydney. Chippendale, NSW: David Ell Press with Longueville Publications. ISBN 0-908197-67-5.

- Wallis, James; Lycett, Joseph (1821). Album of original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett, ca 1817–1818 etc (Digitised version ed.). Manuscripts catalogue, State Library of New South Wales.

- Wallis, James; Oxley, J (1821). Views in New South Wales, 1813–1814 [and] Historical Account of the Colony of NSW, 1820–1821 (Digitised version ed.). Manuscripts catalogue, State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

Further reading

- King, C J (October 1948). "The First Fifty Years of Agriculture in New South Wales – The Agricultural Settlement of the Macquarie Period (1810–1820) – The Township of Sydney". Review of Marketing and Agricultural Economics. 16 (10): 503–529.

- Munger, Jeffrey; Cooney Frelinghuysen, Alice (October 2008). "East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain : Thematic Essays". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Van Dyke, Paul A. (2005). The Canton Trade : Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700–1845. Hong Kong University Press, HKU. ISBN 962-209-749-9. Project MUSE.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sydney punch bowls. |

- Australian History Timeline

- European discovery and the colonisation of Australia

- NSW Colonial Chronology : History Services

- Pinterest – Chinese Export Porcelain : All about Chinese Export Porcelain of the 18th and 19th centuries

- Policing The Rocks. Part 1, 1788–1880 : the Dirt on the Rocks : Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority blog archive