Thalassocracy

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

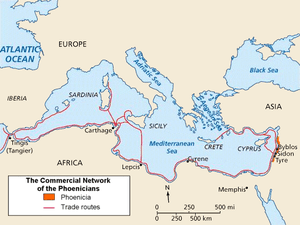

A thalassocracy (from Greek language θάλασσα (thalassa), meaning "sea", and κρατεῖν (kratein), meaning "to rule", giving θαλασσοκρατία (thalassokratia), "rule of the sea") is a state with primarily maritime realms—an empire at sea (such as the Phoenician network of merchant cities) or a sea-borne empire.[1] Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories (for example: Phoenician Tyre, Sidon and Carthage or Srivijaya and Majapahit in Southeast Asia). One can distinguish this traditional sense of thalassocracy from an "empire", where the state's territories, though possibly linked principally or solely by the sea lanes, generally extend into mainland interiors (for example: the Bruneian Empire (1368–1888) in Asia).[2][3] Compare to tellurocracy - land-based hegemony.[4]

The term thalassocracy can also simply refer to naval supremacy, in either military or commercial senses of the word supremacy. The Greeks first used the word thalassocracy to describe the government of the Minoan civilization, whose power depended on its navy.[5] Herodotus distinguishes sea-power from land-power, and also spoke of the need to counter the Phoenician thalassocracy by developing a Greek "empire of the sea". [6]

Examples

There are many ancient examples besides those mentioned above, such as the Delian League. Aside from this example, which was an empire based primarily on naval power and control of waterways and not on any land possessions, the Middle Ages saw its fair share of thalassocracies, often land-based empires which controlled the sea. Among the most famous is the Republic of Venice, conventionally divided in the fifteenth century into the Dogado of Venice and the Lagoon, the Stato di Terraferma of Venetian holdings in northern Italy, and the Stato da Màr of the Venetian outlands bound by the sea:

This was a scattered empire, reminiscent, though on a very different scale, of the Portuguese and later the Dutch empires in the Indian Ocean, a trading-post empire forming a long capitalist antenna; an empire 'on the Phoenician model', to use a more ancient parallel.[7]

In 7th to 15th century Maritime Southeast Asia, the thalassocracies of Srivijaya and Majapahit controlled the sea lanes in Southeast Asia and exploited the spice trade of the Spice Islands, as well as maritime trade routes between India and China.

Nearly contemporaneous, the Republic of Ragusa can be seen as a "thalassocracy", a competitor to Venice.

The Dark Ages (c.500–c.1000) saw many of the coastal cities of the Mezzogiorno develop into minor thalassocracies whose chief powers lay in their ports and their ability to sail navies to defend friendly coasts and ravage enemy ones. These include the variously Greek and Lombard duchies of Gaeta, Naples, Salerno and Amalfi. Later, northern Italy developed its own trade empires based on Pisa and especially the powerful Republic of Genoa, that rivaled with Venice (these three, along with Amalfi, were to be called the Repubbliche marinare, i.e. Sea Republics).

It was with the modern age, the Age of Exploration, that some of the most remarkable thalassocracies emerged. Anchored in their European territories, several nations established colonial empires held together by naval supremacy. First among them was the Portuguese Empire, followed soon by the Spanish Empire, which was challenged by the Dutch Empire, itself replaced on the high seas by the British Empire, whose landed possessions were immense and held together by the greatest navy of its time. With naval arms races (especially between Germany and Britain) and the end of colonialism and the granting of independence to these colonies, European thalassocracies, which had controlled the world's oceans for centuries, ceased to be.

List of examples

- Ancient Carthage

- Athenian Empire

- British Empire

- Brunei Sultanate

- Chola dynasty

- Crown of Aragon

- Dál Riata

- Dorian Confederation

- Duchy of Amalfi

- Dutch Empire

- Empire of Japan

- Frisia

- Hanseatic League

- Kingdom of Butuan

- Kingdom of the Isles

- Kingdom of Tondo

- Liburnia

- Majapahit Empire

- Mataram Kingdom and its successor, Kediri

- Minoan Civilization

- Muscat and Oman

- Phoenicia

- Portuguese Empire

- Republic of Genoa

- Republic of Pisa

- Republic of Ragusa

- Republic of Venice

- Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Sea Peoples Confederation

- Spanish Empire

- Srivijaya Empire

- Sulu Sultanate

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Malacca and its successor, Sultanate of Johor

- Tu'i Tonga Empire

- United States

See also

- Colonialism

- Nomadic empire

- List of countries spanning more than one continent

- List of historical countries and empires spanning more than one continent

- Alfred Thayer Mahan

Notes

- ↑ Alpers, Edward A. (2013). The Indian Ocean in World History. New Oxford World History. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780199929948. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

Portugal's was in every sense a seaborne empire or thalassocracy.

- ↑ P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (21 April 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- ↑ Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (19 February 2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.

- ↑ Lukic, Rénéo; Brint, Michael, eds. (2001). Culture, politics, and nationalism in the age of globalization. Ashgate. p. 103. ISBN 9780754614364. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

Dugin defines 'thalassocracy' as 'power exercised thanks to the sea,' opposed to 'tellurocracy' or 'power exercised thanks to the land' [...]. The 'thalassocracy' here is the United States and its allies; the 'tellurocracy' is Eurasia.

- ↑ D. Abulafia, "Thalassocracies", in P. Horden – S. Kinoshita (eds.), A Companion to Mediterranean History, Oxford, 2014, pp. 139–153, here 139–140.

- ↑ A. Momigliano, "Sea-Power in Greek Thought", The Classical Review, May 1944, 1–7.

- ↑ Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism (Harper & Row) 1984:119.