Thames Barrier

Coordinates: 51°29′52″N 0°02′12″E / 51.4977°N 0.0367°E

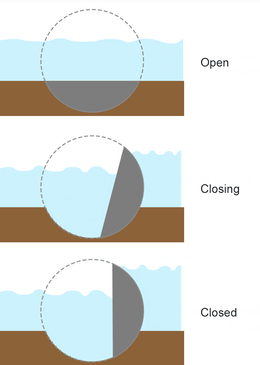

The Thames Barrier is a movable flood barrier in the River Thames east of Central London. It has been operational since 1984 and prevents the floodplain of all but the easternmost boroughs of Greater London from being flooded by exceptionally high tides and storm surges moving up from the North Sea. When needed, it is closed (raised) during high tide; at low tide it can be opened to restore the river's flow towards the sea. Built approximately 3 km (1.9 mi) due east of the Isle of Dogs, its northern bank is in Silvertown in the London Borough of Newham and its southern bank is in the New Charlton area of the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The report of Sir Hermann Bondi on the North Sea flood of 1953 affecting parts of the Thames Estuary and parts of London[1] was instrumental in the building of the barrier.[2]

Geography and background

London is vulnerable to flooding and from heavy tides closing in. A storm surge generated by low pressure in the Atlantic Ocean sometimes tracks eastwards past the north of Scotland and may then be driven into the shallow waters of the North Sea. The surge tide is funnelled down the North Sea which narrows towards the English Channel and the Thames Estuary. If the storm surge coincides with a spring tide, dangerously high water levels can occur in the Thames Estuary.

The threat has increased over time due to the slow but continuous rise in high water levels over the centuries (20 cm (8 inches) per century) and the slow "tilting" of Britain (up in the north and west, and down in the south and east by up to 5 cm (2 inches) per century) caused by post-glacial rebound.

In the 1928 Thames flood, 14 people died. After 300 people died in the UK in the North Sea flood of 1953, the issue gained new prominence. Early proposals for a flood control system were stymied by the need for a large opening in the barrier to allow for vessels from the London docks to pass through. When containerization replaced older forms of shipping and Tilbury was expanded, a smaller barrier became feasible with each of the four main navigation spans being the same width as the opening of Tower Bridge.

History

Design and construction

The concept of the rotating gates was devised by (Reginald) Charles Draper. In 1969, from his parents' house in Pellatt Grove, Wood Green, London, he constructed a working model. The novel rotating cylinders were based on the design of the taps on his gas cooker. The barrier was designed by Rendel, Palmer and Tritton for the Greater London Council and tested at the Hydraulics Research Station, Wallingford. The site at New Charlton was chosen because of the relative straightness of the banks, and because the underlying river chalk was strong enough to support the barrier. Work began at the barrier site in 1974 and construction, which had been undertaken by a Costain/Hollandsche Beton Maatschappij/Tarmac Construction consortium,[3] was largely complete by 1982. The gates of the barrier were made by Cleveland Bridge UK Ltd[4] at Dent's Wharf on the River Tees.[5]

In addition to the barrier, the flood defences for 11 miles down river were raised and strengthened. The barrier was officially opened on 8 May 1984 by Queen Elizabeth II. Total construction cost was around £534 million (£1.6 billion at 2016 prices) with an additional £100 million for river defences, costing altogether £634 million (£1.9 billion in 2016 money) [6]

Built across a 520-metre (570 yd) wide stretch of the river, the barrier divides the river into four 61-metre (200 ft) and two, approximately 30 metre (100 ft) navigable spans. There are also four smaller non-navigable channels between nine concrete piers and two abutments. The flood gates across the openings are circular segments in cross section, and they operate by rotating, raised to allow "underspill" to allow operators to control upstream levels and a complete 180 degree rotation for maintenance. All the gates are hollow and made of steel up to 40 millimetres (1.6 in) thick. The gates are filled with water when submerged and empty as they emerge from the river. The four large central gates are 20.1 metres (66 ft) high and weigh 3,700 tonnes.[7] Four radial gates by the riverbanks, also about 30 metres (100 ft) wide, can be lowered. These gate openings, unlike the main six, are non-navigable.

Predictions for operation

A Thames Barrier flood defence closure is triggered when a combination of high tides forecast in the North Sea and high river flows at the tidal limit at Teddington weir indicate that water levels would exceed 4.87 metres (16.0 ft) in central London. Though Teddington marks the Normal Tidal Limit, in periods of very high fluvial flow the tidal influence can be seen as far upstream as East Molesey, location of the second lock on the Thames.[8][9] Forecast sea levels at the mouth of the Thames Estuary are generated by Met Office computers and also by models run on the Thames Barrier's own forecasting and telemetry computer systems. About 9 hours before the high tide reaches the barrier a flood defence closure begins with messages to stop river traffic, close subsidiary gates and alert other river users. As well as the Thames Barrier, the smaller gates along the Thames Tideway include Barking Barrier, King George V Lock gate, Dartford Barrier and gates at Tilbury Docks and Canvey Island must also be closed. Once river navigation has been stopped and all subsidiary gates closed, then the Thames Barrier itself can be closed. The smaller gates are closed first, then the main navigable spans in succession. The gates remain closed until the tide downstream of the barrier falls to the same level as the water level upstream.

After periods of heavy rain west of London, floodwater can also flow down the Thames from areas upstream of London. Because the river is tidal from Teddington weir all the way through London, this is only a problem at high tide, which prevents the floodwater from escaping out to sea. From Teddington the river is opening out into its estuary, and at low tide it can take much greater flow rates the further one goes downstream. In periods when the river is in flood upstream, if the gates are closed shortly after low tide, a huge empty volume is created behind the barrier which can act as a reservoir to hold the floodwater coming over Teddington weir. Most river floods will not fill this volume in the few hours of the high tide cycle during which the barrier needs to be closed. If the barrier were not there, the high tide would fill up this volume instead, and the floodwater could then spill over the river banks in London. About a third of the closures up to 2009 were to alleviate fluvial flooding.

Barrier closures and incidents

| Season (Sep–Apr) |

Closures per season | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| From tidal flooding | From fluvial flooding | Total[10] | |

| 1982–83 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1983–84 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1984–85 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1985–86 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1986–87 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1987–88 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1988–89 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1989–90 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 1990–91 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1991–92 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1992–93 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 1993–94 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 1994–95 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 1995–96 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 1996–97 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1997–98 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1998–99 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1999–00 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 2000–01 | 16 | 8 | 24 |

| 2001–02 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 2002–03 | 8 | 12 | 20 |

| 2003–04 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2004–05 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 2005–06 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 2006–07 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| 2007–08 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 2008–09 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 2009–10 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 2010–11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011–12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012–13 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2013–14 | 9 | 41 | 50 |

| 2014–15 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015-16 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

During the barrier's entire history up to February 2016, there have been 176 flood defence closures. It costs £16,000 (2008) to close the Thames Barrier on each occasion.[11] The barrier was closed twice on 9 November 2007 after a storm surge in the North Sea which was compared to the one in 1953.[12] The main danger of flooding from the surge was on the coast above the Thames Barrier, where evacuations took place, but the winds abated a little and, at the Thames Barrier, the 9 November 2007 storm surge did not completely coincide with high tide.[13]

On 20 August 1989, hours after the Marchioness disaster, the barrier was closed against a spring tide for 16 hours "to assist the diving and salvage operations".[14]

The barrier has survived 15 boat collisions without serious damage.[15]

On 27 October 1997, the barrier was damaged when the dredger MV Sand Kite, operating in thick fog, hit one of the Thames Barrier's piers. As the ship started to sink she dumped her 3,300 tonne load of aggregate, finally sinking by the bow on top of one of the barrier's gates where she lay for several days. Initially the gate could not be closed as it was covered in a thick layer of gravel. A longer term problem was the premature loss of paint on the flat side of the gate caused by abrasion. The vessel was refloated in mid-November 1997. One estimate of the cost of flooding damage, had it occurred, was around £13 billion.[16]

The annual full test closure in 2012 was scheduled for 3 June to coincide with the Thames pageant celebrating Queen Elizabeth II's Diamond Jubilee. Flood risk manager Andy Batchelor said the pageant gave the Environment Agency "a unique opportunity to test its design for a longer period than we would normally be able to", and that the more stable tidal conditions in central London that resulted would help the vessels taking part.[17]

Ownership and operating authority

The barrier was originally commissioned by the Greater London Council under the guidance of Ray Horner. After the 1986 abolition of the GLC it was operated successively by Thames Water Authority and then the National Rivers Authority until April 1996 when it passed to the Environment Agency.

Future

The barrier was originally designed to protect London against a very high flood level (with an estimated return period of one hundred years) up to the year 2030, after which the protection would decrease, whilst remaining within acceptable limits.[18] At the time of its construction, the barrier was expected to be used 2–3 times per year. It is now being used 6–7 times per year.[19]

This defence level included long-term changes in sea and land levels as understood at that time (c. 1970). Despite global warming and a consequently greater predicted rate of sea level rise, recent analysis extended the working life of the barrier until around 2060–2070. From 1982 until 19 March 2007, the barrier was raised one hundred times to prevent flooding. It is also raised monthly for testing,[20] with a full test closure over high tide once a year.[17]

Released in 2005, a study by four academics contained a proposal to supersede the Thames Barrier with a more ambitious 16 km (10 mi) long barrier across the Thames Estuary from Sheerness in Kent to Southend in Essex.[21]

In November 2011, a new Thames Barrier, further downstream at Lower Hope between East Tilbury in Essex and Cliffe in Kent, was proposed as part of the Thames Hub integrated infrastructure vision. The barrier would incorporate hydropower turbines to generate renewable energy and include road and rail tunnels, providing connections from Essex to a major new hub airport on the Isle of Grain.[22]

In January 2013, in a letter to The Times, a former member of the Thames Barrier Project Management Team, Dr Richard Bloore, stated that the flood barrier was not designed with increased storminess and sea level rises in mind, and called for a new barrier to be looked into immediately.[23][24] The Environment Agency responded that it does not plan to replace the Thames Barrier before 2070,[25] as the barrier was designed with an allowance for sea level rise of 8 mm per year until 2030, which has not been realised in the intervening years.[26] The Thames Barrier is around halfway through its designed lifespan. It was completed in 1982 and was designed to protect London from flooding until 2030 and beyond. The standard of protection it provides will gradually decline over time after 2030, from a 1 in 1000 year event. The Environment Agency are examining the Thames Barrier for its potential design life under climate change, with early indications being that subject to appropriate modification, the Thames Barrier will be capable of providing continued protection to London against rising sea levels until at least 2070.[15][26]

In popular culture

- The 1986 rock music video for "Cross That Bridge" by UK Band "The Ward Brothers" was filmed both inside & outside Thames Barrier #1 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6SRMMNsdIus)

- In the 1982 Alexei Sayle track "'Ullo John! Gotta New Motor?" the barrier is mentioned in the lyrics, "He works on the Thames barrier – he works on the Thames barrier!"

- The climax of Lois McMaster Bujold's 1989 novel Brothers in Arms takes place in and near the Thames Barrier.

- In the tenth episode of Series 5 of Spooks, broadcast in mid-late-2006 an environmental group threatens to blow up the Thames Barrier.

- The Thames Barrier appears in the 2006 Doctor Who Christmas special, "The Runaway Bride". The Doctor and his companion Donna Noble emerge from the barrier after defeating the Empress of the Racnoss and her children by flooding her secret underground lair, only to find out that they have accidentally drained the Thames.

- In 2007 in season 10, episode 5 of Top Gear co-host Jeremy Clarkson drives a racing boat through the Thames Barrier while racing James May, Richard Hammond, and The Stig to London City Airport.

- The barrier features as one of the main locations of Flood, a 2007 British disaster film, directed by Tony Mitchell It features Robert Carlyle, Jessalyn Gilsig, David Suchet and Tom Courtenay. It is based on the 2002 novel of the same name by Richard Doyle.[27]

- The barrier features near the end of the music video for Take That's 2010 hit single, "The Flood".

Gallery

- One of the gates in underspill

Thames Barrier Pier 6

Thames Barrier Pier 6 Gate in maintenance

Gate in maintenance Maintenance close up

Maintenance close up Pier close up

Pier close up Tunnel underneath the Thames Barrier between piers

Tunnel underneath the Thames Barrier between piers

See also

- Barrier Gardens Pier

- Delta Works with the Oosterscheldekering

- Floodgate

- MOSE Project

- Saint Petersburg Dam Flood Prevention Facility Complex

References

- ↑ 1953 floods in Canning Town, Accessed 30 December 2010 Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Herman Bondi, accessed 30 December 2010

- ↑ Environment Agency Archived 17 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Cleveland Bridge UK projects: Thames Barrier Archived 19 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Benring limited: Thames Barrier – subcontracted to Cleveland Bridge UK Ltd". Benring.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ "The Thames Barrier project pack 2010" (PDF). Environment Agency. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.spelthorne.gov.uk/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=6080&p=0

- ↑ Tom de Castella (11 February 2014). "How does the Thames Barrier stop London flooding?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ Environment Agency (24 May 2010). "Thames Barrier closures – indicator two". Environment Agency. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ↑ "Storm Surge Prediction and its Impact on the UK Economy" (PDF). Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ BBC report, accessed 8 December 2007

- ↑ Surge of 9 November 2007 The Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory (POL), (a part of the Natural Environment Research Council)

- ↑ "Part III". Report of the Chief Inspector of Marine Accidents into the collision between the passenger launch Marchioness and MV Bowbelle with loss of life on the River Thames on 20 August 1989 (PDF) (Report). UK Department of Transport Marine Accident Investigation Branch. 5 June 1990. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- 1 2 Hanlon, Michael (18 February 2014). "The Thames Barrier has saved London - but is it time for TB2?". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Report of the Inspector's Inquiry into the collision of MV Sand Kite with the Thames Flood Barrier on 27 October 1997 (PDF) (Report). UK DETR Marine Accident Investigation Branch. April 1999. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Thames Barrier test closure to be on Jubilee pageant day". BBC News. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ Predicting and Managing the Effects of Climate Change on World Heritage, A joint report from the World Heritage Centre, its Advisory Bodies, and a broad group of experts to the 30th session of the World Heritage Committee (Vilnius, 2006) UNESCO, p. 29

- ↑ ThamesWeb Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Times Online 9 January 2005

- ↑ "Thames Hub: An integrated vision for Britain" (PDF). Thames Hub: An integrated vision for Britain. Foster+Partners, Halcrow, Volterra. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ "Letters to the Editor: Thames Barrier". The Times. London. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ "Thames Barrier engineer says second defence needed". BBC News. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Cole, Margo (10 January 2013). "Environment Agency rejects calls for new Thames Barrier". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Thames Barrier Project Pack 2012" (PDF). Environment Agency. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ Phase 9 Entertainment, "Flood" production details. Retrieved 11 January 2011

Further reading

- Stuart Gilbert and Ray Horner. The Thames Barrier Telford 1984 ISBN 0-7277-0249-1

- S Gilbert. The Thames Barrier. Thomas Telford Ltd. 30 June 1986. 216 pages. ISBN 0-7277-0249-1.

- Ken Wilson. The Story of the Thames Barrier. Lanthorn. 1984. 32 pages. ISBN 0-947987-05-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thames Barrier. |

- Thames Barrier page at the Environment Agency

- Animation showing how the Barrier works

- "Time-lapse video showing Thames Barrier operating in flood conditions". Daily Telegraph. 5 January 2014.

- Streetmap of Thames Barrier

- Thames Barrier Information and Learning Centre – on south side of the Thames

- Thames Barrier Park – park by the Barrier on north side of the Thames

- Londons flood defence system

- Map of associated flood barriers

- Risques VS Fictions n°8, filmed interview (subtitled in French) with Steve East, technical support team leader of the real barrier about the depiction of the barrier and scientific accuracy of Flood.