Meiji Constitution

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

Related topics |

|

|

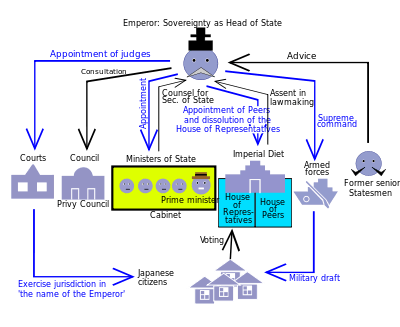

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: 大日本帝國憲法 Shinjitai: 大日本帝国憲法 Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kenpō), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (明治憲法 Meiji Kenpō) was the constitution of the Empire of Japan in force from November 29, 1890 until May 2, 1947. Enacted after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, it provided for a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy, based jointly on the Prussian and British models.[1] In theory, the Emperor of Japan was the supreme ruler, and the Cabinet, whose Prime Minister would be elected by a Privy Council, were his followers; in practice, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime Minister was the actual head of government. Under the Meiji Constitution, the Prime Minister and his Cabinet were not necessarily chosen from the elected members of the Diet.

Through the regular procedure for amendment of the Meiji Constitution, it was entirely revised to become the "Postwar Constitution" on November 3, 1946, which has been in force since May 3, 1947.

Outline

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 provided Japan a form of constitutional monarchy based on the Prusso-German model, in which the Emperor of Japan was an active ruler and wielded considerable political power over foreign policy and diplomacy which was shared with an elected Diet. The Diet primarily dictated domestic policy matters.

After the Meiji Restoration, which restored direct political power to the emperor for the first time in over a millennium, Japan underwent a period of sweeping political and social reform and westernization aimed at strengthening Japan to the level of the nations of the Western world. The immediate consequence of the Constitution was the opening of the first Parliamentary government in Asia.[2]

The Meiji Constitution established clear limits on the power of the executive branch and the Emperor. It also created an independent judiciary. Civil rights and civil liberties were guaranteed, though in many cases they were subject to limitation by law. However, it was ambiguous in wording, and in many places self-contradictory. The leaders of the government and the political parties were left with the task of interpretation as to whether the Meiji Constitution could be used to justify authoritarian or liberal-democratic rule. It was the struggle between these tendencies that dominated the government of the Empire of Japan.

The Meiji Constitution was used as a model for the 1931 Ethiopian Constitution by the Ethiopian intellectual Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam. This was one of the reasons why the progressive Ethiopian intelligentsia associated with Tekle Hawariat were known as "Japanizers".[3]

By the surrender on 2 September 1945, the Empire of Japan was deprived of sovereignty by the Allies, and the Meiji Constitution was suspended. During the Occupation of Japan, the Meiji Constitution was replaced by a new document, the postwar Constitution of Japan. This document—officially an amendment to the Meiji Constitution—replaced imperial rule with a form of Western-style liberal democracy.

History

Background

Prior to the adoption of the Meiji Constitution, Japan had in practice no written constitution. Originally, a Chinese-inspired legal system and constitution known as ritsuryō was enacted in the 6th century (in the late Asuka period and early Nara period); it described a government based on an elaborate and theoretically rational meritocratic bureaucracy, serving under the ultimate authority of the emperor and organised following Chinese models. In theory the last ritsuryō code, the Yōrō Code enacted in 752, was still in force at the time of the Meiji Restoration.

However, in practice the ritsuryō system of government had become largely an empty formality as early as in the middle of the Heian period in the 10th and 11th centuries, a development which was completed by the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1185. The high positions in the ritsuryō system remained as sinecures, and the emperor was de-powered and set aside as a symbolic figure who "reigned, but did not rule" (on the theory that the living god should not have to defile himself with matters of earthly government).

The idea of a written constitution had been a subject of heated debate within and without the government since the beginnings of the Meiji government. The conservative Meiji oligarchy viewed anything resembling democracy or republicanism with suspicion and trepidation, and favored a gradualist approach. The Freedom and People's Rights Movement demanded the immediate establishment of an elected national assembly, and the promulgation of a constitution.

Drafting

On October 21, 1881, Itō Hirobumi was appointed to chair a government bureau to research various forms of constitutional government, and in 1882, Itō led an overseas mission to observe and study various systems first-hand. The United States Constitution was rejected as "too liberal". The French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism. The Reichstag and legal structures of the German Empire, particularly that of Prussia, proved to be of the most interest to the Constitutional Study Mission. Influence was also drawn from the British Westminster system, although it was considered as being unwieldy and granting too much power to Parliament.

He also rejected some notions as unfit for Japan, as they stemmed from European constitutional practice and Christianity.[4] He therefore added references to the kokutai or "national polity" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign.[5]

The Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Itō as Prime Minister. The positions of Chancellor, Minister of the Left, and Minister of the Right, which had existed since the seventh century, were abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution, and to advise Emperor Meiji.

The draft committee included Inoue Kowashi, Kaneko Kentarō, Itō Miyoji and Iwakura Tomomi, along with a number of foreign advisors, in particular the German legal scholars Rudolf von Gneist and Lorenz von Stein. The central issue was the balance between sovereignty vested in the person of the Emperor, and an elected representative legislature with powers that would limit or restrict the power of the sovereign. After numerous drafts from 1886–1888, the final version was submitted to Emperor Meiji in April 1888. The Meiji Constitution was drafted in secret by the committee, without public debate.

Promulgation

The new constitution was promulgated by Emperor Meiji on February 11, 1889, but came into effect on November 29, 1890.[6] The first Imperial Diet, a new representative assembly, convened on the day the Meiji Constitution came into force.[2] The organizational structure of the Diet reflected both Prussian and British influences, most notably in the inclusion of the House of Peers (which resembled the Prussian Herrenhaus and the British House of Lords), and in the formal Speech from the Throne delivered by the Emperor on Opening Day. The second chapter of the constitution, detailing the rights of citizens, bore a resemblance to similar articles in both European and North American constitutions of the day.

Main provisions

Structure

The Meiji Constitution consists of 76 articles in seven chapters, together amounting to around 2,500 words. It is also usually reproduced with its Preamble, the Imperial Oath Sworn in the Sanctuary in the Imperial Palace, and the Imperial Rescript on the Promulgation of the Constitution, which together come to nearly another 1,000 words.[7] The seven chapters are:

- I. The Emperor (1–17)

- II. Rights and Duties of Subjects (18–32)

- III. The Imperial Diet (33–54)

- IV. The Ministers of State and the Privy Council (55–56)

- V. The Judicature (57–61)

- VI. Finance (62–72)

- VII. Supplementary Rules (73–76)

Imperial sovereignty

Unlike its modern successor, the Meiji Constitution was founded on the principle that sovereignty resided in person of the Emperor, by virtue of his divine ancestry "unbroken for ages eternal", rather than in the people. Article 4 states that the "Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in himself the rights of sovereignty". The Emperor, nominally at least, united within himself all three branches (executive, legislative and judiciary) of government, although legislation (article 5) and the budget (article 64) were subject to the "consent of the Imperial Diet". Laws were issued and justice administered by the courts "in the name of the Emperor".

Separate provisions of the Constitution are contradictory as to whether the Constitution or the Emperor is supreme.

- Article 3 declares him to be "sacred and inviolable", a formula which was construed by hard-line monarchists to mean that he retained the right to withdraw the constitution, or to ignore its provisions.

- Article 4 binds the Emperor to exercise his powers "according to the provisions of the present Constitution".

- Article 11 declares that the Emperor commands the army and navy. The heads of these services interpreted this to mean “The army and navy obey only the Emperor, and do not have to obey the cabinet and diet”, which caused political controversy.

- Article 55, however, confirmed that the Emperor’s commands (including Imperial Ordinance, Edicts, Rescripts, etc.) had no legal force within themselves, but required the signature of a “Minister of State”. On the other hand, these “Ministers of State” were appointed by (and could be dismissed by), the Emperor alone, and not by the Prime Minister or the Diet.

Rights and duties of subjects

- Duties: The constitution asserts the duty of Japanese subjects to uphold the constitution (preamble), pay taxes (Article 21) and serve in the armed forces if conscripted (Article 20).

- Qualified rights: The constitution provides for a number of rights that subjects may enjoy where the law does not provide otherwise. These included the right to:

- Freedom of movement (Article 22).

- Not have one's house searched or entered (Article 25).

- Privacy of correspondence (Article 26).

- Private property (Article 27).

- Freedom of speech, assembly and association (Article 29).

- Less conditional rights

- Right to "be appointed to civil or military or any other public offices equally" (Article 19).

- 'Procedural' due process (Article 23).

- Right to trial before a judge (Article 24).

- Freedom of religion (Guaranteed by Article 28 "within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects").

- Right to petition government (Article 30).

Organs of government

The Emperor of Japan had the right to exercise executive authority, and to appoint and dismiss all government officials. The Emperor also had the sole rights to declare war, make peace, conclude treaties, dissolve the lower house of Diet, and issue Imperial ordinances in place of laws when the Diet was not in session. Most importantly, command over the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy was directly held by the Emperor, and not the Diet. The Meiji Constitution provided for a cabinet consisting of Ministers of State who answered to the Emperor rather than the Diet, and to the establishment of the Privy Council. Not mentioned in the Constitution were the genrō, an inner circle of advisors to the Emperor, who wielded considerable influence.

Under the Meiji Constitution, a legislature was established with two Houses. The Upper House, or House of Peers consisted of members of the Imperial Family, hereditary peerage and members appointed by the Emperor. The Lower House, or House of Representatives was elected by direct male suffrage, with qualifications based on amount of tax paid – these qualifications were loosened in 1900 and 1919 with universal adult male suffrage introduced in 1925.[8] Legislative authority was shared with the Diet, and both the Emperor and the Diet had to agree in order for a measure to become law. On the other hand, the Diet was given the authority to initiate legislation, approve all laws, and approve the budget.

Amendments

Amendments to the constitution were provided for by Article 73. This stipulated that, to become law, a proposed amendment had to be submitted first to the Diet by the Emperor through an imperial order or rescript. To be approved by the Diet, an amendment had to be adopted in both chambers by a two-thirds majority of the total number of members of each (rather than merely two-thirds of the total number of votes cast). Once it had been approved by the Diet, an amendment was then promulgated into law by the Emperor, who had an absolute right of veto. No amendment to the constitution was permitted during the time of a regency. Despite these provisions, no amendments were made to the imperial constitution from the time it was adopted until its demise in 1947. When the Meiji Constitution was replaced, in order to ensure legal continuity, its successor was adopted in the form of a constitutional amendment.

However, according to Article 73 of the Meiji Constitution, the amendment should be authorized by the Emperor. Indeed, the 1947 Constitution was authorized by the Emperor (as was declared in the letter of promulgation), which is in apparent conflict of the 1947 Constitution, according to which that constitution was made and authorized by the nation ("the principle of popular sovereignty"). To dissipate such inconsistencies, some peculiar doctrine of "August Revolution" was proposed by Toshiyoshi Miyazawa of the University of Tokyo, but without much persuasiveness.

Notes

- ↑ Hein, Patrick (2009). How the Japanese became foreign to themselves : the impact of globalization on the private and public spheres in Japan. Berlin: Lit. p. 72. ISBN 364310085X.

- 1 2 Arnold, Edwin. "Asia's First Parliament; Sir Edwin Arnold Describes the Step in Japan," New York Times. 26 January 1891.

- ↑ Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia: 1855–1991, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), p. 110

- ↑ W. G. Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan, p 79-80 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ↑ W. G. Beasley,The Rise of Modern Japan, p 80 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ↑ "Old and Modern Japan; The Birth of Constitutional Government. After Centuries of Exclusiveness, the Japanese Adopt Western Forms of Law," New York Times. 13 February 1890.

- ↑ "Japan's Present Crisis and Her Constitution; The Mikado's Ministers Will Be Held Responsible by the People for the Peace Treaty -- Marquis Ito May Be Able to Save Baron Komura," New York Times. 3 September 1905.

- ↑ Griffin, Edward G.; ‘The Universal Suffrage Issue in Japanese Politics, 1918-25 ’; The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (February 1972), pp. 275-290

References

- Akamatsu, Paul. (1972). Meiji 1868: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Japan (Miriam Kochan, translator). New York: Harper & Row.

- Akita, George. (1967). Foundations of constitutional government in modern Japan, 1868–1900. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Beasley, William G. (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804708159; OCLC 579232.

- Beasley, William G. (1995). The Rise of Modern Japan: Political, Economic and Social Change Since 1850. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312127510; OCLC 695042844.

- Craig, Albert M. (1961). Chōshū in the Meiji Restoration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 482814571.

- Jansen, Marius B., and Gilbert Rozman, eds. (1986). Japan in Transition: from Tokugawa to Meiji. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691054599; OCLC 12311985.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674003347; OCLC 44090600.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meiji Constitution. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |