The Letters of Vincent van Gogh

The Letters of Vincent van Gogh refers to a collection of 903 surviving letters written (820) or received (83) by Vincent van Gogh.[1] More than 650 of these were from Vincent to his brother Theo.[2] The collection also includes letters van Gogh wrote to his sister Wil and other relatives, as well as between artists such as Paul Gauguin, Anthon van Rappard and Émile Bernard.[3]

Vincent's sister-in-law and wife to his brother Theo, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, spent many years after her husband's death in 1891 compiling the letters, which were first published in 1914. Arnold Pomerans, editor of a 1966 selection of the letters, wrote that Theo "was the kind of man who saved even the smallest scrap of paper", and it is to this trait that we owe the 663 letters from Vincent. By contrast Vincent infrequently kept letters sent him and just 84 have survived, of which 39 were from Theo.[4][5] Nevertheless, it is to these letters between the brothers that we owe much of what we know today about Vincent van Gogh. Indeed, the only period where we are relatively uninformed is the Parisian period when they shared an apartment and had no need to correspond. The letters effectively play much the same role in shedding light on the art of the period as those between the de Goncourt brothers did for literature.[6]

Background and publication history

Theo van Gogh's wife, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, devoted many years to compiling the letters about which she wrote: "When as Theo's young wife I entered in 1889, our flat in the Cité Pigalle in Paris, I found at the bottom of a small desk a drawer full of letters from Vincent".[3] Within two years both brothers were dead: Vincent as the result of a gunshot wound, and Theo from illness. Joanna began the task of completing the collection, which was published in full in January 1914.[3] That first edition consisted of three volumes, and was followed in 1952–1954 by a four-volume edition that included additional letters. Jan Hulsker suggested, in 1987, that the letters be organized in date order, and undertaking that began in when 1994 the Van Gogh Letter Project was initiated by the Van Gogh museum. The project consists of a complete annotated collection of letters written by and to Vincent.[2][7]

Exhibition and early publication

In the last days of December 1901, running through January 1902, Bruno Cassirer and his cousin Paul Cassirer organized the first van Gogh exhibition in Berlin, Germany. Paul Cassirer first established a market for van Gogh, and then, with the assistance of Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, controlled market prices. In 1906 Bruno Cassirer published a small volume of selected letters of Vincent's to Theo, translated into German.[8]

The letters

Of the 844 surviving letters that van Gogh wrote, 663 were written to Theo, 9 to Theo and Jo. Of the letters Vincent received from Theo, only 39 survive.[9] The first letter was written when Vincent was 19 and begins, "My dear Theo". At that time Vincent was not yet developed as a letter writer – he was factual, but not introspective. When he moved to London, and later to Paris, he began to add more personal information.[10]

Beginning in 1888 and ending a year later, van Gogh wrote 22 letters to Émile Bernard in which the tone is different from those to Theo. In these letters van Gogh wrote more about his techniques, his use of color, and his theories.[11]

The letters as literature

Van Gogh was an avid reader, and his letters reflect his literary pursuits as well as a uniquely authentic literary style.[6] His writing style in the letters reflect the literature he read and valued: Balzac, historians such as Michelet, and naturalists such as Zola, Voltaire and Flaubert.[12] Additionally he read novels written by George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Keats' poetry, reading mostly at night when the light was too poor for painting. Gauguin told him "that he read too much".[13]

Van Gogh scholar Jan Hulsker wrote of van Gogh's letters, "Vincent was able to express himself splendidly, and it is this remarkable writing talent that has secured the letters their lasting place in world literature". Poet W. H. Auden wrote about the letters, "there is scarcely one letter by van Gogh which I ... do not find fascinating".[2] Pomerans believes the letters to be on the level of "world literature" based on style and the ability to express himself. In the letters Vincent reflects different facets of his personality and he adopts a tone specific to his circumstances. At the time he went through a stage of religious fanaticism, his letters fully reflect his thoughts; at the time he was involved with Sien Hoornik his letters reflect his feelings.[6]

The letters as chronicle of an artist's life

Van Gogh's letters paint a chronicle of an artist's life, with the notable omission of the period when he lived in Paris and therefore had no need to correspond with his brother.[6] The letters can be read as an autobiography of an artist; time spent in Brabant, Paris and London, The Hague, Drenthe, Nuenen, Antwerp, Arles, Saint-Remy and Auvers chronicle his corporal travels as well as his artistic growth.[14] Sometimes Vincent wrote Theo every day—beyond the need to acknowledge financial support, describing England and the Netherlands. He included in the letters sketches of common people such as miners and farmers for he believed the poor would inherit the earth.[13] Van Gogh's spiritual and theological thought and convictions are revealed in his letters throughout his life.[15]

Sketches from the letters

.jpg) Sketch of the view from his studio window in letter 200 (F-, JH930).

Sketch of the view from his studio window in letter 200 (F-, JH930)..jpg) Sketch of Roofs Seen from the Artist's Attic Window in letter 251 (F-, JH157).

Sketch of Roofs Seen from the Artist's Attic Window in letter 251 (F-, JH157)..jpg) Sketch of Pollard Willow in letter 252 (F-, JH165).

Sketch of Pollard Willow in letter 252 (F-, JH165). Sketch in letter 261.

Sketch in letter 261. A sketch of the final perspective frame with adjustable legs he had had made in The Hague, 1882.[Letters 1]

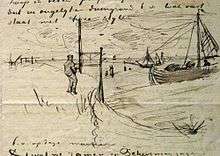

A sketch of the final perspective frame with adjustable legs he had had made in The Hague, 1882.[Letters 1] A sketch illustrating how he planned to use his new perspective frame with adjustable legs in the dunes at Scheveningen, 1882.[Letters 2]

A sketch illustrating how he planned to use his new perspective frame with adjustable legs in the dunes at Scheveningen, 1882.[Letters 2] The Public Soup Kitchen, letter sketch, 1883, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F271)

The Public Soup Kitchen, letter sketch, 1883, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F271) The Public Soup Kitchen, letter sketch, 1883, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F272)

The Public Soup Kitchen, letter sketch, 1883, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F272) Sketch in letter 324 (F-, JH332).

Sketch in letter 324 (F-, JH332). Sketch in letter 323 (F1020, JH333).[Letters 3]

Sketch in letter 323 (F1020, JH333).[Letters 3] Langlois Bridge near Arles, (Sketch from letter to Émile Bernard), March 1888, J. P. Morgan Library, New York City (JH 1370)

Langlois Bridge near Arles, (Sketch from letter to Émile Bernard), March 1888, J. P. Morgan Library, New York City (JH 1370) Vincent's Bedroom in Arles, Letter Sketch October 1888, Pierpont Morgan Library

Vincent's Bedroom in Arles, Letter Sketch October 1888, Pierpont Morgan Library Vincent's Bedroom in Arles, Letter Sketch October 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (JH 1609) letter 554

Vincent's Bedroom in Arles, Letter Sketch October 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (JH 1609) letter 554 Letter to John Peter Russell, 1888, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City

Letter to John Peter Russell, 1888, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City Marguerite Gachet on the Piano, letter sketch, Auvers, June 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (JH 2049)

Marguerite Gachet on the Piano, letter sketch, Auvers, June 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (JH 2049) Sketch of the Sunflower triptych in a letter to Theo.

Sketch of the Sunflower triptych in a letter to Theo. The Yellow House at Arles in letter VGM 491.[Letters 4]

The Yellow House at Arles in letter VGM 491.[Letters 4]

For much of his adult life he was lonely and pushed to learn as much as he could about the world around and about his craft. Margaret Drabble describes the letters from Drenthe as "heart-breaking", as he struggled to come to terms with the "darkness of his hereditary subject matter", the bleak poverty and meanness of Dutch peasant life. This struggle culminated with his painting The Potato Eaters. His friend and mentor Van Rappard disliked the painting. Undeterred, van Gogh moved south, via Antwerp and Paris. His letters from Arles describe his utopian dream of establishing a community of artists who lived together, worked together, and helped each other. In this project he was joined by Paul Gauguin in late 1888.[13]

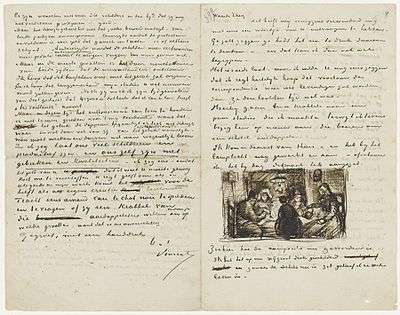

Autograph of letter 716

Letter 716 is a letter sent jointly by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin to Emile Bernard around 1 November 1888 shortly after Gauguin had joined van Gogh in Arles. Late that summer, van Gogh had completed his second group of Sunflower paintings, amongst his most iconic paintings, two of which decorated Gauguin's room, as well as his famous painting The Yellow House depicting the house they shared.

The letter is unique in being a joint letter from the two, and can be read in both the original French and an English translation at the website of the Van Gogh Museum's edition of the letters.[Letters 5] In it they discuss, amongst other matters, their plans to form an artists' commune, possibly abroad. In reality their relationship was always fraught, and by the end of the year they had parted for good, van Gogh himself hospitalised following a breakdown in which he had mutilated one of his ears.

The autograph fetched €445,000 at a sale in Paris 12–13 December 2012.[16]

Letters

- ↑ "Letter 254: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Saturday, 5 or Sunday, 6 August 1882". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 1.

It consists of two long legs ...

- ↑ "Letter 253: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Saturday, 5 August 1882". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. 1v:2.

This is why I’m having a new and, I hope, better perspective frame made ...

- ↑ "Letter 323: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Saturday, 3 March 1883". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 1.

Herewith a scratch of the selling of soup that I did in the public soup kitchen.

- ↑ "691 To Theo van Gogh. Arles, on or about Saturday, 29 September 1888". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. 1v:2.

Likewise croquis of a square no. 30 canvas showing the house and its surroundings under a sulphur sun, under a pure cobalt sky. That’s a really difficult subject! But I want to conquer it for that very reason. Because it’s tremendous, these yellow houses in the sunlight and then the incomparable freshness of the blue.

All the ground’s yellow, too. I’ll send you another, better drawing of it than this croquis from memory; the house to the left is pink, with green shutters; the one that’s shaded by a tree, that’s the restaurant where I go to eat supper every day. My friend the postman lives at the bottom of the street on the left, between the two railway bridges. The night café that I painted isn’t in the painting; it’s to the left of the restaurant.

Milliet finds it horrible ... - ↑ "716 Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin to Emile Bernard. Arles, Thursday, 1 or Friday, 2 November 1888". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. 1.

Next, I don’t think it will astonish you greatly if I tell you that our discussions are tending to deal with the terrific subject of an association of certain painters.

References

- ↑ "Overview of all the letters". Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Van Gogh as letter-writer". Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Pomerans (1997), xiii

- ↑ "List of letters to Vincent van Gogh". Van Gogh Museum.

- ↑ "List of letters to Vincent van Gogh from Theo van Gogh". Vincent van Gogh.

- 1 2 3 4 Pomerans (1997), xv–xvii

- ↑ "Publication history: The first collected edition of 1952-1954 and thereafter". Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ The date 1908 proposed in The posthumous fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970, by John Rewald, (first published in Museumjournaal, August–September 1970), John Rewald Studies in Post-Impressionism, p. 248, published by Abrams 1986, ISBN 0-8109-1632-0

- ↑ "Van Gogh as Writer" Retrieved December 16.

- ↑ "The Earliest Letters"

- ↑ Lubow, Arthur. "Letters from Vincent". Smithsonian. Volume 38, Issue 10. (2008).

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), xx

- 1 2 3 Drabble, Margaret (18 January 2010). "Dutch Courage". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), xxiii

- ↑ Edwards, Cliff (1989). Van Gogh and God : a creative spiritual quest. Chicago, Ill.: Loyola University Press. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- ↑ "VAN GOGH, Vincent (1853-1890) et GAUGUIN, Paul (1848-1903). Lettre autographe signée à Émile Bernard [Arles 1er ou 2 novembre 1888]" (in French). Christie's. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Letters by Vincent van Gogh. |

- Jansen, Leo; Luijen, Hans; Bakker, Nienke. Vincent van Gogh – The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition. London, Thames & Hudson, 2009. ISBN 978-0-500-23865-3

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh In Saint-Rémy and Auvers (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1986. ISBN 0-87099-477-8

- Pomerans, Arnold; de Leeuw, Ronald. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London: Penguin Classics, 1997. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and by Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2

Further reading

- Drabble, Margaret. "Dutch Courage". New Statesman. (18 January 2010).

- Shiff, Richard. "The Myth behind the Man". New York Times Book Review. 9 February 1986.

- "Vincent van Gogh: Painted with Words: The Letters to Émile Bernard". Publishers Weekly. (27 August 2007). Vol 254, Issue 34.

External links

- Johanna van Gogh-Bonger's memoir

- Memoir by her son.

- Vincent van Gogh Gallery. The complete works and letters of Vincent van Gogh.

- Van Gogh Letters – The complete letters of Van Gogh, translated into English and annotated. Published by the Van Gogh Museum.

- Memoir of Vincent van Gogh. By Johanna Gesina van Gogh-Bonger, Vincent's sister in law.

- Van Gogh's Letters, unabridged and annotated.

- The Letters of Vincent van Gogh: A Critical Study. By Patrick Grant

- Van Gogh as critic and self-critic, a 1973 exhibition catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries