Thelodonti

| Thelodonti Temporal range: 453–359 Ma Middle–Late Ordovician[1] to Late Devonian[2] | |

|---|---|

| |

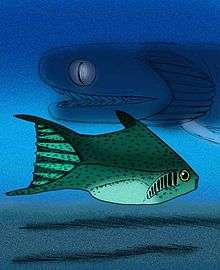

| Among the flat-bodied forms are Lanarkia (top left), provided with long, spine-shaped scales, and Loganellia (top right and middle). Other thelodonts, such as Furcacauda from the Devonian of Canada (bottom) are deep-bodied, with lateral gill openings and a very large, forked tail.[3] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Thelodonti Jaekel, 1911 |

| Orders | |

Thelodonti (from Greek: "feeble teeth")[4] is a class of extinct jawless fishes with distinctive scales instead of large plates of armor.

There is much debate over whether the group of Palaeozoic fish known as the Thelodonti (formerly coelolepids[5]) represent a monophyletic grouping, or disparate stem groups to the major lines of jawless and jawed fish.

Thelodonts are united in possession of "thelodont scales". This defining character is not necessarily a result of shared ancestry, as it may have been evolved independently by different groups. Thus the thelodonts are generally thought to represent a polyphyletic group,[6] although there is no firm agreement on this point; if they are monophyletic, there is no firm evidence on what their ancestral state was.[7]:206

"Thelodonts" were morphologically very similar, and probably closely related, to fish of the classes Heterostraci and Anaspida, differing mainly in their covering of distinctive, small, spiny scales. These scales were easily dispersed after death; their small size and resilience makes them the most common vertebrate fossil of their time.[8][9]

The fish lived in both freshwater and marine environments, first appearing during the Ordovician, and perishing during the Frasnian–Famennian extinction event of the Late Devonian. They were predominantly deposit-feeding bottom dwellers, although there is evidence to suggest that some species took to the water column to be free-swimming organisms.

Description

Very few complete thelodont specimens are known; fewer still are preserved in three dimensions. This is due in part to the lack of an internal ossified (i.e. bony) skeleton; it does not help that the scales are poorly, if at all, attached to one another, and that they readily detach from their owners upon death.

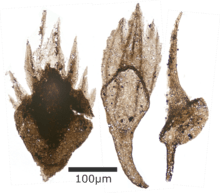

Consequently, it is a better option to describe the exoskeleton, instead, which was composed of many tooth-like scales, usually around 0.5-1.5mm in size. These scales did not overlap,[10] were aligned to point backwards along the fish, in the most streamlined direction, but beyond that often appear haphazard in their orientation. The scales themselves approximate the form of a teardrop mounted on a small, bulky base, with the base often containing a small rootlet with which the scale was attached to the fish. The "teardrop" often contains lines, ridges, furrows and spikes running down its length in an array of sometimes complex patterns.[11] Scales found around the gill region were generally smaller than the larger, bulkier scales found on the dorsal/ventral sides of the fish; some genera display rows of longer spikes.[12]

The scaly covering contrasts them with most other jawless fishes, which were armor-plated with large, flat scales.

Aside from scattered scales, some specimens do appear to display imprints, giving an indication of the structure of the whole animal - which appeared to reach 15–30 cm in length.[13] Tentative studies appear to suggest that the fish possessed a more developed braincase than the lampreys, with an almost shark-like outline. Internal scales have also been recovered, some fused into plates resembling gnathostome tooth-whorls to such a degree that some researchers favour a close link between the families.[11]

Despite the rarity of complete fossils, these very rare intact specimens do allow us to gain an insight into the innards of the Thelodonts. Some specimens described in 1993 were the first to be found with a significant degree of three-dimensionality, ending speculations that the Thelodonts were flattened fish. Further, these fossils allowed the gut morphology to be interpreted, which generated much excitement: their guts were unlike those of any other agnathans, and a stomach was clearly visible: this was unexpected, as it was previously thought that stomachs evolved after jaws. Distinctive fork-shaped tails - usually characteristic of the jawed fish (gnathostomes) - were also found, linking the two groups to an unexpected degree.[14]

The fins of the thelodonts are useful in reconstructing their mode of life. Their paired pectoral fins combined with single, usually well-developed, dorsal and anal fins;[13] these and the prolonged anterior tube-like handle, followed by a heterocercal tail resemble features of modern fish that associated with their deftness at predation and evasion.[12]

Taxonomy

Because the paucity of intact fossils, especially since some families are known entirely from scale fossils, taxonomy of thelodonts is based primarily on scale morphology.

A recent assessment of thelodont taxonomy by Wilson and Märss in 2009 merges the orders Loganelliiformes, Katoporiida and Shieliiformes into Thelodontiformes, places families Lanarkiidae and Nikoliviidae into Furcacaudiformes (because of scale morphology) and establishes Archipelepidiformes as the basal-most order.[15]

Scales

The bony scales of the thelodont group, as the most abundant form of fossil, are also the best understood - and thus most useful. The scales were formed and shed throughout the organisms' lifetimes, and quickly separated after their death.[5]

Bone - being one of the most resistant materials to the process of fossilisation - often preserves internal detail, which allows the histology and growth of the scales to be studied in detail. The scales comprise a non-growing "crown" composed of dentine, with a sometimes-ornamented enameloid upper surface and an aspidine base.[16] Its growing base is made of cell-free bone, which sometimes developed anchorage structures to fix it in the side of the fish.[11] Beyond that, there appear to be five types of bone-growth, which may represent five natural groupings within the thelodonts - or a spectrum ranging between the end members meta- (or ortho-) dentine and mesodentine tissues.[17] Interestingly, each of the five scale morphs appears to resemble the scales of more derived groupings of fish, suggesting that thelodont groups may have been stem groups to succeeding clades of fish.[11]

However, using scale morphology alone to distinguish species has some pitfalls. Within each organism, scale shape varies hugely according to body area,[18] with intermediate forms appearing between different areas - and to make matters worse, scale morphology may not even be constant within one area. To confuse things further, scale morphologies are not unique to taxa, and may be indistinguishable on the same area of two different species.[13]

The morphology and histology of the thelodonts provides the main tool for quantifying their diversity and distinguishing between species - although ultimately using such convergent traits is prone to errors. Nonetheless, a framework comprising three groups has been proposed based upon scale morphology and histology.[17]

Ecology

Most thelodonts were probably deposit feeders, although nektonic forms were probably filter-feeders.. They are mainly known from open shelf environments, but are also found nearer the shore and in some freshwater settings.[8] The appearance of the same species in fresh- and salt-water settings has led to suggestions that some thelodonts migrated into fresh water, perhaps to spawn. However, the transition from fresh- to salt- water should be observable, as the scales' composition would change to reflect the different environment. This compositional change has not yet been found.[19]

Utility as biostratigraphic markers

Thelodont scales are globally widespread during the Silurian and Early Devonian times, becoming restricted in range to Gondwana, until their extinction in the Late Devonian (Frasnian).[11] The morphology of some species diversified rapidly enough for the scales to rival the conodonts in utility as biostratigraphic markers, allowing precise correlation of widely spaced sediments.

Evolutionary patterns

The first major pattern or group of jawless fish with exoskeletons or plated armour, was the Laurentian group, which existed during the Cambrian-Ordovician time. However, the thelodonts (as well as the conodonts, placoderms, acanthodians, and chondrichthyans) are the second major group which are believed to have emerged in the middle Ordovician and lasted near the Late Devonian period. Due to their similar characteristics and chronological time frame of existence, many believe the thelodonts have Laurentian origins.[20]

See also

Further reading

| Wikispecies has information related to: Thelodonti |

- Long, John A. (1996). The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5438-5.

- A range of images of scales are available in Märss, T. (2006). "Thelodonts (Agnatha) from the basal beds of the Kuressaare Stage, Ludlow, Upper Silurian of Estonia" (PDF). Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences. Geology. 55 (1): 43–66.

References

- ↑ Märss, T.; V. N. Karatajūtė-Talimaa (2002). "Ordovician and Lower Silurian thelodonts from Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago (Russia)" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 24 (2): 381–404.

- ↑ Turner, S.; R. S. Dring (1981). "Late Devonian thelodonts (Agnatha) from the Gneudna Formation, Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia". Alcheringa. 5: 39–48. doi:10.1080/03115518108565432.

- ↑ Janvier, Philippe (1997) Thelodonti The Tree of Life Web Project.

- ↑ Maisey, John G., Craig Chesek, and David Miller. Discovering fossil fishes. New York: Holt, 1996.

- 1 2 Turner, S.; Tarling, D. H. (1982). "Thelodont and other agnathan distributions as tests of Lower Paleozoic continental reconstructions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 39 (3–4): 295–311. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(82)90027-X.

- ↑ Sarjeant, William Antony S.; L. B. Halstead (1995). Vertebrate fossils and the evolution of scientific concepts: writings in tribute to Beverly Halstead. ISBN 978-2-88124-996-9.

- ↑ Donoghue, P. C., P. L. Forey & R. J. Aldridge (2000). "Conodont affinity and chordate phylogeny". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 191–251. doi:10.1017/S0006323199005472. PMID 10881388.

- 1 2 Turner, S. (1999). "Early Silurian to Early Devonian thelodont assemblages and their possible ecological significance". In A. J. Boucot; J. Lawson. Palaeocommunities, International Geological Correlation Programme 53, Project Ecostratigraphy, Final Report. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–78.

- ↑ The early and mid Silurian. See Kazlev, M.A., White, T (March 6, 2001). "Thelodonti". Palaeos.com. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ↑ Turner, S. (1973). "Siluro-Devonian thelodonts from the Welsh Borderland". Journal of the Geological Society. 129 (6): 557–584. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.129.6.0557.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janvier, Philippe (1998). "Early vertebrates and their extant relatives". Early Vertebrates. Oxford University Press. pp. 123–127. ISBN 0-19-854047-7.

- 1 2 Donoghue, P. C. J.; M. P. Smith (2001). "The anatomy of Turinia pagei (Powrie), and the phylogenetic status of the Thelodonti". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 92 (1): 15–37. doi:10.1017/S0263593301000025.

- 1 2 3 Botella, H.; J. I. Valenzuela-Rios; P. Carls (2006). "A New Early Devonian thelodont from Celtiberia (Spain), with a revision of Spanish thelodonts". Palaeontology. 49 (1): 141–154. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00534.x.

- ↑ Wilson, Mark V. H. & Michael W. Caldwell (1993). "New Silurian and Devonian fork-tailed 'thelodonts' are jawless vertebrates with stomach and deep bodies". Nature. 361 (6441): 442–444. Bibcode:1993Natur.361..442W. doi:10.1038/361442a0.

- ↑ Wilson, Mark VH, and Tiiu Märss. "Thelodont phylogeny revisited, with inclusion of key scale-based taxa." Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences 58.4 (2009): 297œ310.

- ↑ Märss, T. (2006). "Exoskeletal ultrasculpture of early vertebrates". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (2): 235–252. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[235:EUOEV]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Turner, S. (1991). "Monophyly and interrelationships of the Thelodonti". In M. M. Chang, Y. H. Liu & G. R. Zhang. Early Vertebrates and Related Problems of Evolutionary Biology. Science Press, Beijing. pp. 87–119.

- ↑ Märss, T. (1986). "Squamation of the thelodont agnathan Phlebolepis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/02724634.1986.10011593.

- ↑ Märss, T. (1992). "The structure of growth layers of Silurian fish scales as potential evidence of environmental changes". Academia. 1: 41–48.

- ↑ M. Paul Smith, Philip C. J. Donoghue & Ivan J. Sansom (2002). "The spatial and temporal diversification of Early Palaeozoic vertebrates" (PDF). Special Publications. Geological Society. 194: 69–72. Bibcode:2002GSLSP.194...69S. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2002.194.01.06.

External links

- Fossil Museum. "Immense Thelodont Fossil Fish from Silurian Scotland". Contains some images.

- Mikko's Phylogeny Archive (February 26, 2006). "Thelodonti – thelodonts". A phylogeny.