Tris Speaker

| Tris Speaker | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Center fielder / Manager | |||

|

Born: April 4, 1888 Hubbard, Texas | |||

|

Died: December 8, 1958 (aged 70) Whitney, Texas | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 14, 1907, for the Boston Americans | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| August 30, 1928, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .345 | ||

| Hits | 3,515 | ||

| Home runs | 117 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,529 | ||

| Doubles | 792 | ||

| Managerial record | 617–520 | ||

| Winning % | .543 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player

As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

MLB Records

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Inducted | 1937 | ||

| Vote | 82.1% (second ballot) | ||

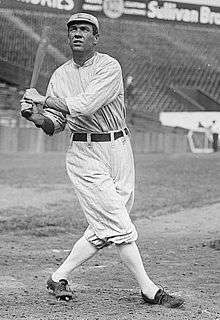

Tristram Edgar Speaker (April 4, 1888 – December 8, 1958), nicknamed "The Grey Eagle", was an American baseball player. Considered one of the best offensive and defensive center fielders in the history of Major League Baseball (MLB), he compiled a career batting average of .345 (sixth all-time[1]). His 792 career doubles represent an MLB career record. His 3,514 hits are fifth in the all-time hits list. Defensively, Speaker holds career records for assists, double plays, and unassisted double plays by an outfielder. His fielding glove was known as the place "where triples go to die."[2]

After playing in the minor leagues in Texas and Arkansas, Speaker debuted with the Boston Red Sox in 1907. He became the regular center fielder by 1909 and led the Red Sox to World Series championships in 1912 and 1915. In 1915, Speaker's batting average dropped to .322 from .338 the previous season; he was traded to the Cleveland Indians when he refused to take a pay cut. As player-manager for Cleveland, he led the team to its first World Series title. In ten of his eleven seasons with Cleveland, he finished with a batting average greater than .350. Speaker resigned as Cleveland's manager in 1926 after he and Ty Cobb faced game fixing allegations; both men were later cleared. During his managerial stint in Cleveland, Speaker introduced the platoon system in the major leagues.

Speaker played with the Washington Senators in 1927 and the Philadelphia Athletics in 1928, then became a minor league manager and part owner. He later held several roles for the Cleveland Indians. Late in life, Speaker led a short-lived indoor baseball league, ran a wholesale liquor business, worked in sales and chaired Cleveland's boxing commission. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. He was named 27th [3] in the Sporting News 100 Greatest Baseball Players (1999) and was also included in the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

Early life

Speaker was born on April 4, 1888, in Hubbard, Texas, to Archie and Nancy Poer Speaker.[4] As a youth, Speaker broke his arm after he fell from a horse; the injury forced him to become left-handed.[5] In 1905, Speaker played a year of college baseball for Fort Worth Polytechnic Institute. Newspaper reports have held that Speaker suffered a football injury and nearly had his arm amputated around this time;[6] biographer Timothy Gay characterizes this as "a story that the macho Speaker never disspelled [sic]."[7] He worked on a ranch before beginning his professional baseball career.[8]

Speaker's abilities drew the interest of Doak Roberts, owner of the Cleburne Railroaders of the Texas League, in 1906. After losing several games as a pitcher, Speaker converted to outfielder to replace a Cleburne player who had been struck in the head with a pitch.[5] He batted .318 for the Railroaders. Speaker's mother opposed his participation in the major leagues, saying that they reminded her of slavery.[9] Though she relented, for several years Mrs. Speaker questioned why her son had not stayed home and entered the cattle or oil businesses.[10]

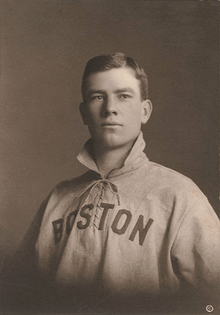

He performed well for the Texas League's Houston Buffaloes in 1907, but his mother stated that she would never allow him to go to the Boston Americans. Roberts sold the youngster to the Americans for $750 or $800 (equal to $19,079 or $20,351 today).[11] Speaker played in seven games for the Americans in 1907, with three hits in 19 at bats for a .158 average. In 1908, Boston Americans owner John I. Taylor changed the team's name to the Boston Red Sox after the bright socks in the team's uniform.[12] That year, the club traded Speaker to the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern League in exchange for use of their facilities for spring training.[13] Speaker batted .350 for the Travelers and his contract was repurchased by the Red Sox. He logged a .224 batting average in 116 at bats.[14]

Major league career

Early years

Speaker became the regular starting center fielder for Boston in 1909 and light-hitting Denny Sullivan was sold to the Cleveland Naps. Speaker hit .309 in 143 games as the team finished third in the pennant race.[15] Defensively, Speaker was involved in 12 double plays, leading the league's outfielders, and had a .973 fielding percentage, third among outfielders.[16] In 1910 the Red Sox signed left fielder Duffy Lewis. Speaker, Lewis and Harry Hooper formed Boston's "Million-Dollar Outfield", one of the finest outfield trios in baseball history. Speaker was the star of the Million-Dollar Outfield. He ran fast enough that he could stand very close to second base, effectively giving the team a fifth infielder, but he still caught the balls hit to center field.[17] In 1910 and 1911, Boston finished fourth in the American League standings.[18][19]

Speaker's best season came in 1912. He played every game and led the American League (AL) in doubles (53) and home runs (10). He set career highs with 222 hits, 136 runs, 580 at-bats, and 52 stolen bases.[14] Speaker's stolen base tally was a team record until Tommy Harper stole 54 bases in 1973.[20] He batted .383 and his .567 slugging percentage was the highest of his dead-ball days. Speaker set a major league single-season record with three hitting streaks of twenty or more games (30, 23, and 22). He also became the first major leaguer to hit 50 doubles and steal 50 bases in the same season. In August, Speaker's mother unsuccessfully attempted to convince him to quit baseball and come home.[21] In Fenway Park's first game, Speaker drove in the winning run in the 11th inning, giving Boston the 7–6 win.

The 1912 Red Sox won the AL pennant, finishing 14 games ahead of the Washington Senators and 15 games ahead of the Philadelphia Athletics. In the 1912 World Series, Speaker led the Red Sox to their second World Series title by defeating John McGraw's New York Giants. After the second game was called on account of darkness and ended in a tie, the series went to eight games. The Red Sox won the final game after Fred Snodgrass dropped an easy fly ball and later failed to go after a Speaker pop foul. After the pop foul, Speaker tied the game with a single. The Red Sox won the game in the bottom of the tenth inning. He finished the series with a .300 batting average, nine hits and four runs scored. Speaker was named the AL Most Valuable Player (MVP) for 1912.[22] Though he did not lead the league in any offensive categories in 1913, Speaker finished fourth in AL MVP voting.[14]

Speaker batted .338 and tied his career high of 12 double plays as an outfielder in 1914.[14][16] He hit .322 in 1915.[14] The Red Sox beat the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1915 World Series. The Red Sox were led by pitcher Babe Ruth, who was playing in his first full season. Ruth won 18 games and hit a team-high four home runs. Speaker got five hits, including a triple, in 17 at-bats during the series. He scored twice but did not drive in any runs.[23]

Traded to the Indians

After 1915, Red Sox president Joseph Lannin wanted Speaker to take a pay cut from about $15,000 (equal to $351,464 today) to about $9,000 (equal to $210,878 today) because of the drop in his batting average; Speaker refused and offered $12,000 ($281,171 today). On April 8, 1916, Lannin traded Speaker to the Cleveland Indians.[24] In exchange, Boston received Sad Sam Jones, Fred Thomas and $50,000 ($1,089,144 today). The angry Speaker held out until he received $10,000 (equal to $217,829 today) of the cash that Boston collected.[25] With an annual salary of $40,000 (equal to $871,315 today), Speaker was the highest paid player in baseball.[26] Speaker hit over .350 in nine of his eleven years with Cleveland. In 1916, he led the league in hits, doubles, batting average, slugging percentage and on-base percentage.[14] Cobb had won the previous nine consecutive AL batting titles; Speaker outhit him with a .386 batting average compared to Cobb's .371.[27]

The center field fence at Cleveland's Dunn Field was 460 feet from home plate until it was shortened to 420 feet in 1920.[28] Even so, Speaker played so shallow in the outfield that he was able to execute six career unassisted double plays at second base, catching low line drives on the run and then beating baserunners to the bag. At least once he was credited as the pivot man in a routine double play. He was often shallow enough to catch pickoff throws at second base.[29] At one point, Speaker's signature move was to come in behind second base on a bunt and make a tag play on a baserunner who had passed the bag.[30]

While in Cleveland, Speaker participated in diverse activities off the baseball field. Speaker enrolled in an aviator training program in 1918.[31] Though World War I ended less than two months after he enrolled, Speaker completed his training and served in the naval reserves for several years.[32] He also owned a ranch in Texas and competed in roping events during the baseball offseason.[33]

Stint as player-manager

From the day that Speaker arrived in Cleveland, manager Lee Fohl rarely made an important move without consulting him. George Uhle recalled an incident from 1919 during his rookie year with the Indians. Speaker often signaled to Fohl when he thought that a pitcher should be brought in from the bullpen. One day, Fohl misread Speaker's signal and brought in a different pitcher than Speaker had intended. To avoid the appearance of overruling his manager, Speaker let the change stand. Pitcher Fritz Coumbe lost the game, Fohl resigned that night and Speaker became manager. Uhle said that Speaker felt bad for contributing to Fohl's departure.[34]

Speaker guided the 1920 Indians to their first World Series win. In a crucial late season game against the second-place White Sox, Speaker caught a hard line drive hit to deep right-center field by Shoeless Joe Jackson, ending the game. On a dead run, Speaker leaped with both feet off the ground, snaring the ball before crashing into a concrete wall. As he lay unconscious from the impact, Speaker still held the baseball.[35] In the 1920 World Series against Brooklyn, Speaker hit an RBI triple in the deciding game, which the Indians won 3–0.[36] Cleveland's 1920 season was also significant due to the death of Ray Chapman on August 17. Chapman died after being hit in the head by a pitch from Carl Mays. Chapman had been asked about retirement before the season, and he said that he wanted to help Speaker earn Cleveland's first World Series victory before thinking of retirement.[37]

During that championship season, Speaker is credited with introducing the platoon system, which attempted to match right-handed batters against left-handed pitchers and vice versa. Sportswriter John B. Sheridan was among the critics of the system, saying, "The specialist in baseball is no good and won't go very far... The whole effect of the system will be to make the players affected half men... It is farewell, a long farewell to all that player's chance of greatness... It destroys young ball players by destroying their most precious quality – confidence in their ability to hit any pitcher, left or right, alive, dead, or waiting to be born."[38] Baseball Magazine was supportive, pointing out that Speaker had results that backed up his system.[38]

The 1921 Indians remained in a tight pennant race all year, finishing 4 1⁄2 games behind the Yankees. The Indians did not seriously contend for the pennant from 1922 through 1925.[38] Speaker led the league in doubles eight times, including every year between 1920 and 1923.[14] He led the league's outfielders in fielding percentage in 1921 and 1922.[16] On May 17, 1925, Speaker became the fifth member of the 3,000 hit club when he hit a single off pitcher Tom Zachary of the Washington Senators. Only Napoleon Lajoie had previously accomplished the feat as a member of the Indians.[39]

AL President Ban Johnson asked Speaker and Detroit manager Cobb to resign their posts after a scandal broke in 1926. Pitcher Dutch Leonard claimed that Speaker and Cobb fixed at least one game between Cleveland and Detroit. In a newspaper column published shortly before the hearings were to begin, Billy Evans characterized the accusations as "purely a matter of personal revenge" for Leonard. The pitcher was said to be upset with Cobb and Speaker after a trade ended with Leonard in the minor leagues.[40] When Leonard refused to appear at the January 5, 1927 hearings to discuss his accusations, Commissioner Landis cleared both Speaker and Cobb of any wrongdoing. Both were reinstated to their original teams, but each team declared its manager free to sign elsewhere. Speaker did not return to big league managing and he finished his MLB managerial career with a 617–520 record.[41]

At the time of his 1926 resignation, news reports described Speaker as permanently retiring from baseball to pursue business ventures.[42] However, Speaker signed to play with the Washington Senators for 1927.[43] Cobb joined the Philadelphia Athletics. Speaker joined Cobb in Philadelphia for the 1928 season; he played part-time and finished with a .267 average.[44] Prior to that season, Speaker had not hit for a batting average below .300 since 1908.[14]

Speaker's major league playing career ended after 1928. He retired with 792 doubles, an all-time career record as of 2014.[14] Defensively, Speaker holds the all-time career records (as of 2013) for assists as an outfielder and double plays as an outfielder.[16] He remains the last batter to hit 200 triples in a career.

Later life

In 1929 Speaker replaced Walter Johnson as the manager of the Newark Bears of the International League.[45] In two seasons with Newark, he also appeared as a player in 59 games.[46] When Speaker resigned during his second season, the Bears were in seventh place after a sixth-place finish in 1929.[47] In January 1933 he became a part owner and manager of the Kansas City Blues.[48] By May, Speaker had been replaced as manager but remained secretary of the club.[49] By 1936, he had sold his share of the team.[50] In 1937, Speaker was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame during its second year of balloting. He was honored at the hall's first induction ceremony in 1939.[51]

After his playing and managing days, Speaker was an entrepreneur and salesman. By 1937, Speaker had opened a wholesale liquor business and worked as a state sales representative for a steel company.[52] He chaired Cleveland's boxing commission between 1936 and 1943. Newspaper coverage credited Speaker with several key reforms to boxing in Cleveland, including the recruitment of new officials and protections against fight fixing. Under Speaker, fight payouts went directly to boxers rather than managers.[53] Speaker sorted out a scheduling conflict for a 1940 boxing match in Cleveland involving former middleweight champion Teddy Yarosz.[54] Yarosz defeated Jimmy Reeves in ten rounds and the fight attracted over 8,300 spectators.[55]

In 1937, Speaker sustained a 16-foot fall while working on a flower box near a second-story window at his home. Upon admission to the hospital, he underwent facial surgery. He was described as having "better than an even chance to live" and was suffering from a skull fracture, a broken arm and possible internal injuries.[56] He ultimately recovered.[57]

In 1939, Speaker was president of the National Professional Indoor Baseball League. The league had teams in New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Cincinnati and St. Louis.[58] The league shut down operations due to poor attendance only two months after its formation.[59] Speaker was one of the founders of Cleveland's Society for Crippled Children and he helped to promote the society's rehabilitation center, Camp Cheerful.[60] Speaker served as vice president of the society, ran fundraising campaigns and received a distinguished service award from the organization.[61] He became seriously ill with pneumonia in 1942.[62] Speaker ultimately recovered, but Gay characterized Speaker's condition as "touch-and-go for several days".[63]

In 1947, Speaker returned to baseball as "ambassador of good will" for Bill Veeck and the Cleveland Indians.[64] He remained in advisory, coaching or scouting roles for the Indians until his death in 1958. In an article in the July 1952 issue of SPORT, Speaker recounted how Veeck hired him in 1947 to be a coaching consultant to Larry Doby, the first black player in the AL and the second in the major leagues. Before the Indians had signed Doby, he was the star second baseman of the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues. A SPORT photograph that accompanied the article shows Speaker mentoring five members of the Indians: Luke Easter, Jim Hegan, Ray Boone, Al Rosen and Doby. Speaker was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in 1951. Texas was the first state to establish a state sports hall of fame and Speaker was in its inaugural induction class.[65]

Death

Speaker died of a heart attack on December 8, 1958, at the age of 70, at Lake Whitney, Texas. He collapsed as he and a friend were pulling their boat into the dock after a fishing trip. It was his second heart attack in four years.[66] Speaker was buried at Fairview Cemetery in Hubbard, Texas.[67]

After Speaker's death, Cobb said, "Terribly depressed. I never let him know how much I admired him when we were playing against each other... It was only after we finally became teammates and then retired that I could tell Tris Speaker of the underlying respect I had for him." Lajoie said, "He was one of the greatest fellows I ever knew, both as a baseball player and as a gentleman."[68] Former Boston teammate Duffy Lewis said, "He was a team player. As great a hitter as he was, he wasn't looking out for his own average ... Speaker was the bell cow of our outfield. Harry Hooper and I would watch him and know how to play the hitters."[69]

Legacy

S is for Speaker,

Swift center-field tender,

When the ball saw him coming,

It yelled, "I surrender."

— Ogden Nash, Sport magazine (January 1949)[70]

Immediately after Speaker's death, the baseball field at the city park in Cleburne, Texas was renamed in honor of Speaker.[67] In 1961, the Tris Speaker Memorial Award was created by the Baseball Writers' Association of America to honor players or officials who make outstanding contributions to baseball.[71] In 1999, he ranked number 27 on the Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players. He was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[72][73] Speaker is mentioned in the poem "Line-Up for Yesterday" by Ogden Nash.[74]

In 2008, former baseball players' union chief Marvin Miller, trying to defend the recently retired catcher Mike Piazza against claims that he should not be elected to the Hall of Fame because of association with the use of steroids, on the basis that the Hall of Fame has various unsavory people in it, opined that Speaker should be removed from the Hall of Fame because of alleged membership in the Ku Klux Klan. Miller said, "Some of the early people inducted in the Hall were members of the Ku Klux Klan: Tris Speaker, Cap Anson, and some people suspect Ty Cobb as well. I think that by and large, the players, and certainly the ones I knew, are good people. But the Hall is full of villains."[75] Miller's comment about Anson has no basis, other than speculating that he could have been a Klansman since he was a racist during his playing career, which ended in 1897, although he was umpiring games with black players by 1901, including featuring the all-black Columbia Giants. Miller, age 91 at the time the 2008 article appeared, is the earliest source for declaring that it is factual that Anson was a member of the Klan, based purely on an Internet search of sources that try to link Anson to the Klan. By contrast, Speaker-Cobb-Rogers Hornsby biographer Charles C. Alexander, a Klan expert in his general history writings, told fellow baseball author Marty Appel, apparently referring to the 1920s (Anson died in 1922), “As I’ve suggested in the biographies, it’s possible that they [Speaker, Cobb and Hornsby] were briefly in the Klan, which was very strong in Texas and especially in Fort Worth and Dallas. The Klan went all out to recruit prominent people in all fields, provided they were native born, Protestant and white.”[76]

Baseball historian Bill James does not dispute this claim in apparently referring to Speaker and possibly Cobb, but says that the Klan had toned down its racist overtures during the 1920s and pulled in hundreds of thousands of non-racist men, including Hugo Black.[77] James adds that Speaker was a staunch supporter of Doby when he broke the American League color barrier, working long hours with the former second baseman on how to play the outfield.[78]

Regular season statistics

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | TB | SH | HBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2789 | 10195 | 1882 | 3514 | 792 | 222 | 117 | 1529 | 432 | 129 | 1381 | 220 | .345 | .428 | .500 | .928 | 5101 | 309 | 103 |

See also

- 3,000 hit club

- Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame

- Hitting for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball doubles records

- List of Major League Baseball hit records

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball triples records

Notes

- ↑ "Career Leaders & Records for Batting Average". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ↑ Gay, p. 130

- ↑ 100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac

- ↑ Speaker, Tristram E. Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- 1 2 Speaker, Tris (May 19, 1916). "How I Became the Highest-Priced Star in Big Leagues". Toledo News-Bee. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Vaughan, Doug (September 19, 1939). "On The Rebound". The Windsor Daily Star. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ↑ Gay, p. 41

- ↑ Snyder, Dean (August 1, 1921). "Tris Speaker Throws a Mean Rope". The Southeast Missourian. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Speaker is Crowned King of All Baseball Players; Star Becomes Famous When His Team Takes Lead". The Gazette Times. June 29, 1912. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ↑ Gay, p. 48

- ↑ Jim Sandoval, Bill Nowlin, Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and their Profession, 2011, page 2

- ↑ Nichols, John (2007). The Story of the Boston Red Sox. The Creative Company. p. 8. ISBN 1583414819.

- ↑ "Red Sox Paid Rent with Tris Speaker". The Day. April 12, 1916. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Tris Speaker Batting Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker, Outfielder, Dies; Ex-Star for Red Sox and Indians". The New York Times. December 9, 1958. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tris Speaker Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Swings Last Bat". The Vancouver Sun. December 9, 1958. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ "1910 American League Team Statistics and Standings". Sports Reference, LLC. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "1911 American League Team Statistics and Standings". Sports Reference, LLC. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Browne, Ian. "Harper reflects back on racial turmoil in Boston". MLB.com. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Speaker's Mother Wants Him to Quit". The St. Petersburg Independent. August 27, 1912. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ↑ Richards, Steve (September 29, 1999). "Speaker: First Sox Who Got Away". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 30, 2013. via HighBeam Research.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker World Series Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Sold to Cleveland Club". New York Times. 9 April 1916. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ McMane, Fred (2000). The 3,000 Hit Club. Sports Publishing, LLC. p. 43.

- ↑ Grabowski, John (1992). Sports in Cleveland: An Illustrated History. Indiana University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0253207479.

- ↑ Webster, Gary (2012). Tris Speaker and the 1920 Indians: Tragedy to Glory. McFarland. p. 17. ISBN 0786467967.

- ↑ Johnson, Bill. "League Park (Cleveland)". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Pluto, Terry (August 1, 1995). "For Speaker, 3,000 a Hit". The Cedartown Standard. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Joe (February 9, 1928). "Speaker Longs to Cavort on One More Championship Club". Toledo News-Bee. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Speaker Seeks to be Aviator". New York Times. 21 October 1918. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ Gay, p. 181

- ↑ Snyder, Dean (August 1, 1921). "Speaker Throws a Mean Rope". Cape Girardeau Southeast Missourian. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Murdock, Eugene (1991). Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920–1940. New York: Macklermedia. p. 200. ISBN 0-88736-235-4.

- ↑ McMane, Fred (2012). The 3,000 Hit Club: Stories of Baseball's Greatest Hitters. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 1613213018.

- ↑ "Speaker Again Stars; Indians are Champions". The Milwaukee Journal. October 12, 1920. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Chapman Planned to Retire After Helping Speaker Win His Pennant". The Deseret News. August 18, 1920. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Steinberg, Steve (June 22, 2010). "Manager Speaker". The Baseball Research Journal. Retrieved July 30, 2013. via HighBeam Research.

- ↑ "The 3,000 Hit Club: Tris Speaker". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Evans, Billy (December 27, 1926). "Charges Against Cobb And Speaker Made By Pitcher "Dutch" Leonard Were Prompted By Personal Grudge". Beaver Falls Tribune. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Schneider, Russell (2004). The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing, LLC. p. 322. ISBN 1582618402.

- ↑ "Speaker Resigns Cleveland Indian Post". The Milwaukee Sentinel. November 30, 1926. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Griffith Grabs Veteran With Phone Talk". The Milwaukee Sentinel. February 1, 1927. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Neyer, Rob (2003). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Lineups. Simon & Schuster. p. 247. ISBN 0743241746.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Signs to Manage Newark Team in Minor Loop". The Washington Daily Reporter. November 12, 1928. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Quits Newark". San Jose Evening News. November 27, 1930. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Blues Are Sold". St. Joseph Gazette. January 28, 1933. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Levy, Sam (May 28, 1933). "Tris Speaker Bawled Out Manager in His First Regular League Start". The Milkwaukee Journal. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Speaker Deplores Lack of Color in Baseball". The Milwaukee Journal. May 14, 1936. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker". Sports Reference, LLC. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ McCann, Richard (March 17, 1937). "Tris Speaker's Three Jobs Keep Him Hustling Like a Browns' Outfielder". The Telegraph-Herald. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Quitting Boxing Body". St. Petersburg Times. October 31, 1943. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Old Tris Settles Ring Date Mixup". Toledo Blade. March 25, 1940. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Teddy Yarosz Scores Easy Victory Over Jimmy Reeves". The Daily Times. April 16, 1940. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker May Recover from His Injury in Fall". Reading Eagle. April 12, 1937. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker to Speak at Oldtimers Banquet". Reading Eagle. January 20, 1952. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Indoor League Is Organized". The Milwaukee Journal. November 15, 1939. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "National Indoor Baseball League Halts Activities". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. December 23, 1939. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Editorials: Tris Speaker". Lewiston Evening Journal. December 9, 1958. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker Awarded Medal For His Service". The Portsmouth Times. April 14, 1944. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Speaker is Sure He'll Get Well". Portsmouth Times. July 12, 1942. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ Gay, p. 271

- ↑ "Veeck Adds Tris Speaker as Good Will Ambassador". The Milwaukee Sentinel. January 24, 1947. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Texas Sports Hall of Fame". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Tris Speaker, Baseball Immortal, Dies in Texas". Schenectady Gazette. December 9, 1958. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- 1 2 "Tris Speaker Funeral Today". St. Petersburg Times. December 11, 1958. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Cobb Pays Great Tribute To Old Rival". Toledo Blade. December 9, 1958. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Lewis is Shocked by Speaker's Death". The Milwaukee Journal. December 9, 1958. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Line-Up For Yesterday by Ogden Nash". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ↑ "Yogi Wins Tris Speaker Award". Ocala Star-Banner. January 6, 1963. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". Baseball-Almanac.com. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ "The All-Century Team". MLB.com. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Line-Up For Yesterday by Ogden Nash". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Jaffe, Jay (May 29, 2008). "Prospectus Hit and Run". Baseball Prospectus. Baseball Prospectus. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Appel, Marty. "Historian puts spotlight on Cobb and Speaker"., Sports Collectors Digest, December 21, 2007. Anson biographer Rosenberg did the Internet search on July 22, 2016, and added the citation to Alexander's article, to point out Miller's imbalance in weighting Anson versus Cobb, plus the juxtaposing of a Bill James comment that lacks a page citation and which likely is not referring to Anson on this subject. For Anson umpiring games with black players, see Rosenberg, Howard W. "Fantasy Baseball: The Momentous Drawing of the Sport's 19th-Century 'Color Line' is still Tripping up History Writers"., The Atavist, June 14, 2016

- ↑ James, Bill (December 31, 2008). "The New Bill James Historical Abstract". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ↑ Grigsby, Daryl Russell (2012). Celebrating Ourselves: African-Americans and the Promise of Baseball. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 978-160844-798-5. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

References

Gay, Timothy M. (2007). Tris Speaker: The Rough-and-Tumble Life of a Baseball Legend. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 1599211114.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tris Speaker. |

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- (profile) Baseball Library

- Tris Speaker at the Internet Movie Database

- Tris Speaker The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

| Preceded by Ed Delahanty |

Single season doubles record holders 1923–1925 |

Succeeded by George Burns |