Twenty Bucks

| Twenty Bucks | |

|---|---|

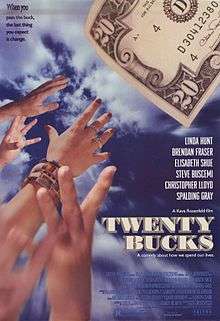

Theatrical Release Poster | |

| Directed by | Keva Rosenfeld |

| Produced by | Karen Murphy |

| Written by |

Leslie Bohem Endre Bohem |

| Starring | |

| Music by | David Robbins |

| Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki |

| Edited by | Michael Ruscio |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures |

Release dates | October 22, 1993 (U.S. release) |

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Twenty Bucks is a 1993 film that follows the travels of a $20 bill from its delivery via armored car in an unnamed American city through various transactions and incidents from person to person.

The star of the movie is a $20 bill, series 1988A, serial number L33425849D. Linda Hunt, Brendan Fraser, Gladys Knight, Elisabeth Shue, Steve Buscemi, Christopher Lloyd, William H. Macy, David Schwimmer, Shohreh Aghdashloo and Spalding Gray all appeared in the film.

Plot

An armored truck brings money to load an ATM. A woman withdraws $20 but the bill slips away. A homeless woman, Angeline (Linda Hunt), grabs the bill and reads the serial number, proclaiming that it is her destiny to win the lottery with those numbers. As she holds the bill, a boy grabs the bill from her and uses it at a bakery. The baker sells an expensive pair of figurines for a wedding cake to Jack Holiday (George Morfogen) and gives him the bill as change. At the rehearsal dinner for the upcoming wedding of Sam Mastrewski (Brendan Fraser) to Anna Holiday (Sam Jenkins), Jack reminisces about exchanging his foreign money for American currency when he first came to America, and he presents Sam with the $20 bill as a wedding present. Sam is taken aback by the perceived cheapness of his father-in-law-to-be, but is quickly "kidnapped" for his bachelor party, where he uses the bill to pay the stripper (Melora Walters). Anna shows up to explain that the $20 is not the entire present and suggests they frame it to show that they understand its significance. Sam is unable to explain the absence of the bill, when the stripper comes in from the fire escape to offer it back to him. Anna apparently breaks the engagement.

The stripper uses the $20 bill to buy a herbal remedy from Mrs. McCormac (Gladys Knight). Mrs. McCormac mails the bill to her grandson Bobby (Willie Marlett) as a birthday present. Bobby goes to a convenience store where Frank (Steve Buscemi) and Jimmy (Christopher Lloyd) are engaged in a string of robberies. (During their spree, they prevent Angeline from buying a lottery ticket at a liquor store.) Not knowing he's a robber, the underage Bobby gives Jimmy the $20 bill to buy him wine. Jimmy goes into the store to find that Frank has botched the robbery. Jimmy and Frank leave, giving Bobby and his girlfriend Peggy champagne. The police chase the robbers, who hide in a used car lot. After the police pass by, Jimmy and Frank split up the money, but when Frank sees the $20 Jimmy got from the kid, he assumes that Jimmy is holding out on him. Jimmy tries to explain but Frank pulls a shotgun on him. Jimmy shoots Frank and takes all the money they've stolen, but leaves the $20 bill. The bill, now dripped with Frank's blood, winds up in the police evidence locker but falls into the wrong box.

Waitress and aspiring writer Emily Adams (Elisabeth Shue) shows up at the police precinct with boyfriend Neil (David Schwimmer) to claim some items the police recovered. The police officer (William H. Macy) unwittingly includes the $20 bill. After flying out of the box from the back seat of Emily's convertible, the bill floats around town, and is picked up by a homeless man who uses it to buy groceries. (In this scene, Angeline is again unable to buy a lottery ticket.) The bill is given as change to a wealthy woman who uses it to snort cocaine off the back of her stretch limousine, although she leaves it on her car, where it is picked up by the drug dealer (Edward Blatchford).

The drug dealer also runs a day camp for youth, and he puts the bill into a fish where it is caught by a teen who has it converted to quarters and uses them to call a phone sex hotline in a bowling alley. The bowling alley owner (Ned Bellamy) gives the bill to his lover (Matt Frewer) and tells him to go out and have fun. The Frewer character encounters Sam, who is loitering in a daze behind the bowling alley. Sam turns down an offer of the $20 bill, not knowing it is the cause of his downfall. The Frewer character then uses it to play bingo at a church, where the priest is portrayed by Spaulding Gray. Emily's father, Bruce (Alan North) also plays bingo and receives the bill as change before dying of a heart attack.

At the mortuary, the mortician (Melora Walters), gives the family Bruce's personal effects, including his wallet with the $20 bill. Emily eventually looks in the wallet and finds the $20 bill in the wallet together with a copy of her first published short story. Her mother Ruth (Diane Baker) explains that Bruce also wanted to be a writer. Emily decides to go to Europe. At the airport, she explains her decision to her brother Gary (Kevin Kilner), and she melodramatically rips up the bill in front of him. (Gary was a witness to one of Jimmy & Frank's robberies.) Sam is also at the airport, waiting for a flight to Europe and having a drink with Jack, with the two clearing up the misunderstanding over the $20 bill on good terms. Sam uses a piece of the ripped up bill as a bookmark but it falls out without him noticing it as Sam and Emily walk toward their gate, both striking up a conversation. A title reading "The End" is derailed by Angeline collecting pieces of the bill.

Angeline sits down at a coin-operated TV and patches the bill back together. Just then the lottery numbers are read, and to her agony, they match the serial number of the bill. She goes to a bank and inquires if the bill is still any good. The teller explains that if there's more than 51% of the bill left, it is still valid, and hands Angeline a crisp new $20 bill. The homeless woman dramatically reads the serial number of the new bill and leaves the bank.

Production

The film was based on a screenplay that was nearly 60 years old. It was originally written by Endre Bohem in 1935, but was never filmed; his son, Leslie, discovered it in the 1980s and revised it, modernizing the language and some of the plot. This version of the screenplay was then used for the film.[Note 1] The elder Bohem wrote his spec script soon after the release of If I Had a Million.[Note 2]

In one of the production featurettes, Rosenfeld says that the bills used in the production were figured into the production costs of the film. The producers obtained several bills with consecutive serial numbers, as well as "every thousandth bill" so that some bills would have the right first few digits of the serial number and others the right last few digits. The bills were then selectively damaged in specific ways as required by the script. When they were done with the bills, Rosenfeld says the bills were dropped into the petty cash fund money.

Filming locations

Most of the outdoor scenes were filmed in Minneapolis; the rest and nearly all of the indoor scenes were filmed in Los Angeles. The scene where Angeline captures the bill was filmed on North 4th Street in downtown Minneapolis, in front of Fire Station No. 10 (with traffic driving the wrong way for the movie). The scene where Angeline visits McCormac and McCormac mails the bill (and Jimmy and Frank meet) was filmed in the 1000 block of West Broadway in Minneapolis (now demolished). The supermarket scene was filmed at a Holiday Plus supermarket (now part of the Cub Foods chain) in suburban Minneapolis. The bill floats near the Mississippi River just above St. Anthony Falls; over the 3rd Avenue Bridge; and past the E-Z Stop gas station at 1624 Washington Ave. North. The Adams house was filmed on the Near North side of Minneapolis at 1802 Bryant Ave N near the E-Z Stop station. The final scene was filmed in an actual bank, Marquette Bank Minneapolis at 90 S. 6th Street, which is now a restaurant named Bank.

Critical and scholarly reception

While many critics saw the film as a series of uneven vignettes,[3] Roger Ebert thought that "the very lightness of the premise gives the film a kind of freedom. We glimpse revealing moments in lives, instead of following them to one of those manufactured movie conclusions that pretends everything has been settled."[1] Ebert was so engrossed by Christopher Lloyd's performance that he almost forgot about the film's title object,[Note 3] and liked the movie as a whole while acknowledging its vignette construction.

Scholars have compared this film to other films and television shows which track a single object traded among various persons (such as Diamond Handcuffs, Tales of Manhattan, The Gun (1974), Dead Man's Gun (1997), The Red Violin, etc.)[2] However, by emphasizing a ubiquitous object rather than a unique object (such as the auction-worthy violin in The Red Violin), this film "ushers the genre into heretofore unexplored territory."[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "The story of Endre Boehm's original screenplay is almost as problematic as the fate of the $20 bill. He wrote this story in 1935. It gathered dust for more than half a century before he handed it to his son, Leslie, who read it, liked it, did a rewrite, and saw it into production."[1]

- ↑ "Passed from Hungarian émigré scenarist Endre Bohem to his son Leslie Bohem, who inherited and adapted the 1935 version in the early 1980s, the story began as a Hollywood spec script not long after If I Had a Million was released. If I Had a Million proved to be an influence on the elder Bohem, who felt a more relevant and plausible film for Depression-era audiences would focus on twenty rather than a million dollars. Though the unproduced script languished for decades, the updated rendering perceptively deconstructs economic disparities that could not have been addressed in the original."[2]

- ↑ "Sometimes an actor will walk into a movie for 15 minutes or so, and show you such strength that you look at him altogether differently. That's what Lloyd does here ... He doesn't play the holdup man as a bad guy, but as a well-spoken, intelligent, logical, firm-minded character who has a chilling reserve. By the time his segment arrives at its unexpected conclusion, I was so absorbed, I'd basically forgotten about the 20 bucks and the rest of the movie."[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Roger Ebert, Review of Twenty Bucks Chicago Sun-Times, April 8, 1994.

- 1 2 3 David Scott Diffrient, "Stories that Objects Might Live to Tell: The "Hand-Me-Down" Narrative in Film" Other Voices 3 1 (2007). Accessed April 7, 2008.

- ↑ Mick Martin & Marsha Porter, DVD & Video Guide 2005 New York: Random House Publishing Group (2004), p. 1440