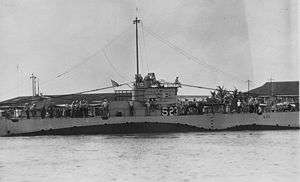

USS S-23 (SS-128)

S-23 in an undated photograph | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS S-23 |

| Builder: | Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation |

| Laid down: | 18 January 1919 |

| Launched: | 27 October 1920 |

| Commissioned: | 30 October 1923 |

| Decommissioned: | 2 November 1945 |

| Struck: | 16 November 1945 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | S-class submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 219 ft 3 in (66.83 m) |

| Beam: | 20 ft 8 in (6.30 m) |

| Draft: | 15 ft 11 in (4.85 m) |

| Speed: |

|

| Complement: | 42 officers and men |

| Armament: |

|

| Service record | |

| Operations: | World War II |

| Victories: | 1 battle star |

USS S-23 (SS-128) was a first-group (S-1 or "Holland") S-class submarine of the United States Navy. Her keel was laid down on 18 January 1919 by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation's Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was launched on 27 October 1920 sponsored by Miss Barbara Sears, and commissioned on 30 October 1923 with Lieutenant Joseph Y. Dreisonstok in command.

Service history

Early years

Initially assigned to Submarine Division 11, Control Force, S-23 was based at New London, Connecticut through the 1920s. During that time, she operated off the New England coast from late spring until early winter then moved south for winter and spring exercises. From 1925 on, her annual deployments included participation in fleet problems; and those maneuvers occasionally took her from the Caribbean Sea into the Pacific Ocean. With the new decade, however, the submarine was transferred to the Pacific; and, on 5 January 1931, she departed New London for the Panama Canal, California, and Hawaii. En route, she participated in Fleet Problem XII and, on 25 April, she arrived at her new home port, Pearl Harbor, whence she operated, with Division 7, for the next ten years. In June 1941, Division 7 became Division 41, and, on 1 September, S-23 departed the Hawaiian Islands for California. An overhaul and operations off the West Coast took her into December when the United States entered World War II.

The crew of the World War I-design submarine then prepared for service in the Aleutian Islands. Radiant-type heaters were purchased in San Diego, California, to augment the heat provided by the galley range. Heavier and more waterproof clothing, including ski masks, were added to the regular issue provided to submarine crews. The boat itself was fitted out for wartime service and, in January 1942, S-23 moved north to Dutch Harbor, Unalaska.

First war patrol

On the afternoon of 7 February, she departed Dutch Harbor on her first war patrol. Within hours, she encountered the heavy seas and poor visibility which characterized the Aleutians. Waves broke over the bridge, battering those on duty there, and sent water cascading down the conning tower hatch. On 10 February, S-23 stopped to jettison torn sections of the superstructure, a procedure she was to repeat on her subsequent patrols; and, on 13 February, the heavy seas caused broken bones to some men on the bridge. For another three days, the submarine patrolled the great circle route from Japan, then headed home, arriving at Dutch Harbor on 17 February. From there, she was ordered back to San Diego for overhaul and brief sound school duty.

On her arrival, requests were made for improved electrical, heating, and communications gear and installation of a fathometer, radar, and keel-mounted sonar. The latter requests were to be repeated after each of her next three patrols, but became available only after her fourth patrol.

Abortive patrol

On 20 May, S-23 again sailed for the Aleutians. Proceeding via Port Angeles, Washington, she arrived in Alaskan waters on 29 May and was directed to patrol to the west of Unalaska to hinder an anticipated Japanese attack. On 2 June, however, 20-foot (6.1 m) waves broke over the bridge and seriously injured two men. The boat headed for Dutch Harbor to transfer the men for medical treatment. Arriving the same day, she was still in the harbor the following morning when Japanese carrier-based planes attacked the base.

Second war patrol

After the first raid, S-23 cleared the harbor and within hours arrived in her assigned patrol area where she remained until 11 June. She was then ordered back to Dutch Harbor; replenished; and sent to patrol southeast of Attu, which the Japanese had occupied, along with Kiska, a few days earlier.

For the next 19 days, she hunted for Japanese logistic and warships en route to Attu and reconnoitered that island's bays and harbors. Several attempts were made to close targets, but fog, slow speed, and poor maneuverability precluded attacks in all but one case. On 17 June, she fired on a tanker, but did not score. On 2 July, she headed back to Unalaska and arrived at Dutch Harbor early on the morning of 4 July.

Third war patrol

During her third war patrol, 15 July to 18 August, S-23 again patrolled primarily in the Attu area. On 6 August, however, she was diverted closer to Kiska to support the bombardment of the island; and, on 9 August, she returned to her patrol area, where her previous experiences in closing enemy targets were repeated.

Fourth war patrol

Eight days after her return to Dutch Harbor, S-23 again headed west, and, on 28 August, she arrived in her assigned area to serve as a protective scout during the occupation of Adak. During most of her time on station, the weather was overcast, but it proved to be the most favorable she had experienced in eight months of Alaskan operations. On 16 September, she was recalled from patrol to meet her 20 September scheduled date of departure for San Diego for upkeep and sound school duty.

Fifth war patrol

On 7 December, S-23 returned to Unalaska, and, on 17 December, she got underway on her fifth war patrol. By 22 December, she was off western Attu; and, on 23 December, she received orders to take up station off Paramushiro. On 24 December, she headed for the Kuril Islands. Two days later, 200 miles (320 km) from her destination, her stern plane operating gear outside the hull broke. Since submerging and depth control became difficult, she turned back for Dutch Harbor. Moving east, her mechanical difficulties increased; her stern planes damaged her propellers; her fouled rudder resulted in a damaged gear train. Nature added severe snow and ice storms after 3 January 1943. But, on 6 January, S-23 made it into Dutch Harbor.

Using equipment and parts from sister ship USS S-35, S-23 was repaired at Dutch Harbor and at Kodiak; and, on 28 January, she departed her Unalaska base for another patrol in the Attu area. She spent 21 days on station, two of which, 6 and 7 February, were spent repairing the port main motor control panel. She scored on no enemy ships and returned to Dutch Harbor on 26 February.

Sixth war patrol

Refit, the submarine got underway for her last war patrol on 8 March. Moving west, she arrived off the Kamchatka Peninsula on 14 March and encountered floes with ice 2.5–3 feet (0.76–0.91 m) thick. Her progress down the coast in search of the Japanese fishing fleet slowed, and, initially limited to moving during daylight hours, she rounded Cape Kronotski on the afternoon of 16 March and Cape Lopatka on the morning of 19 March. She then set a course back to the Aleutians which would take her across Japanese Kuril-Aleutians supply lanes. On 26 March, she took up patrol duty in the Attu area; and, on 31 March, she turned her bow toward Dutch Harbor.

Retirement

In April 1943, S-23 returned to San Diego. During the summer, she underwent an extensive overhaul; and, in the fall, she began providing training services to the sound school which she continued through the end of hostilities. On 11 September 1945, she sailed for San Francisco, California, where she was decommissioned on 2 November. Fourteen days later, her name was struck from the Naval Vessel Register. Her hulk was subsequently sold for scrapping and was delivered to the purchaser, Salco Iron and Metal Company, San Francisco, on 15 November 1946.

S-23 was awarded one battle star for her World War II service.

References

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.