Holodomor genocide question

| Part of a series on the |

| Holodomor |

|---|

| Historical background |

| Soviet government |

|

Institutions

Policies |

| Responsible parties |

| Investigation and comprehension |

The Holodomor genocide question consists of the attempts to determine whether the Holodomor, the catastrophic man-made[1] famine of 1933 that claimed millions of lives in Ukraine,[2] was an ethnic genocide or an unintended result of the "Soviet regime's [re-direction of already drought-reduced[3] grain supplies to attain] economic and political goals."[4] The event is recognized as a crime against humanity by the European Parliament,[5] and a genocide in Ukraine,[6] while the Russian Federation considers it part of the wider Soviet famine of 1932–33 and corresponding famine relief effort.[4] The debate among historians is ongoing and there is no international consensus among scholars or governments on whether the Soviet policies that caused the famine fall under the legal definition of genocide.[7][8]

Holodomor

The Ukrainian famine (1932–1933), or Holodomor (Ukrainian: Голодомор) (literally in Ukrainian, "death by starvation"), was one of the largest national catastrophes in the modern history of the Ukrainian nation. The word comes from the Ukrainian words holod, 'hunger', and mor, 'plague',[9] possibly from the expression moryty holodom, 'to inflict death by hunger'. The Ukrainian verb "moryty" (морити) means "to poison somebody, drive to exhaustion or to torment somebody". The perfect form of the verb "moryty" is "zamoryty"—"kill or drive to death by hunger, exhausting work". The neologism "Holodomor" is given in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language as "artificial hunger, organised in vast scale by the criminal regime against the country's population".[10] Sometimes the expression is translated into English as "murder by hunger."[11]

Ukrainian government position

On November 28, 2006, Ukraine's parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, passed a law recognizing the 1932–1933 Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. The voting figures were as follows: supporting the bill were BYuT—118 deputies, NSNU—79 deputies, Socialists—30 deputies, 4 independent deputies, and the Party of Regions—2 deputies (200 deputies did not cast a vote). The Communist Party of Ukraine voted against the bill. In all, 233 deputies supported the bill—more than the minimum of 226 votes required to pass it into law.[12][13] Another bill was sought by Yushchenko's administration to criminalize those disputing that the Holodomor was genocide, but such a law has never been adopted by the Ukrainian parliament[14]

In a ruling of January 13, 2010, Kyiv's Court of Appeal recognized the leaders of the totalitarian Bolshevik regime as those guilty of 'genocide against the Ukrainian national group in 1932-33 through the artificial creation of living conditions intended for its partial physical destruction.'"[15]

Russian government position

The Russian Federation accepts historic information about the Holodomor but rejects the argument that it was ethnic genocide by pointing out the fact that millions of non-Ukrainian Soviet citizens also died because of the famine. On 2 April 2008, a statement was voted by the Russian parliament stating there was no evidence that the 1933 famine was an act of genocide specifically against the Ukrainian people. This was in response to the 2006 Ukrainian parliament declaration that the Holodomor was an act of genocide by the Soviet authorities against the Ukrainian people. The resolution adopted by Russia's lower house of parliament, the State Duma, condemned the Soviet regime's "disregard for the lives of people in the attainment of economic and political goals", along with "any attempts to revive totalitarian regimes that disregard the rights and lives of citizens in former Soviet states." yet stated that "there is no historic evidence that the famine was organized on ethnic grounds."[4]

According to a Moscow Times article: "The Kremlin argues that genocide is the killing of a population based on their ethnicity, whereas Stalin's regime annihilated all kinds of people indiscriminately, regardless of their ethnicity. But if the Kremlin really believed in this argument, it would officially acknowledge that Stalin's actions constituted mass genocide against all the people of the Soviet Union."[16]

In November 2010 a leaked confidential U.S. diplomatic cable revealed that Russia had allegedly pressured its neighbors not to support the designation of Holodomor as a genocide at the United Nations.[17]

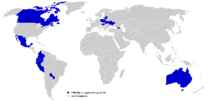

Other countries and international organizations

Several countries and international organizations made public statements addressing the Holodomor and recognizing it as a tragedy. Some went further to recognize it as genocide, or a crime against humanity.

In the framework of international organizations, resolution recognizing Holodomor as genocide was adopted by the Baltic Assembly.[18][19]

A number of international organizations adopted resolutions recognizing Holodomor as tragedy or crime against humanity but did not use the word "genocide":

- European Parliament[5]

- General Assembly of the United Nations[20][21]

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe[22][23][24][25]

- Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe[26][27]

- United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture[28][29][30]

The following countries have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide:[31]

-

Australia[32][33]

Australia[32][33] -

Canada[34][35]

Canada[34][35] -

Colombia[36][37]

Colombia[36][37] -

Ecuador[38][39]

Ecuador[38][39] -

Estonia

Estonia -

Georgia

Georgia -

Hungary

Hungary -

Latvia

Latvia -

Lithuania

Lithuania -

Mexico

Mexico -

Paraguay

Paraguay -

Peru

Peru -

Poland[40][41]

Poland[40][41] -

Vatican City[42]

Vatican City[42]

Countries that have recognized the Holodomor as a criminal act of the Stalinist regime:

Scholarly debate

Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin in his work "Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine", the last chapter of a monumental History of Genocide, written in the 1950s, applies the concept of genocide to the destruction of the Ukrainian nation and not just Ukrainian peasants during the Holodomor. In his work he speaks of: a) the decimation of the Ukrainian national elites, b) destruction of the Orthodox Church, c) the starvation of the Ukrainian farming population, and d) its replacement with non-Ukrainian population from the RSFSR as integral components of the same genocidal process. The only dimension not included in Lemkin's analysis was the destruction of the 8,000,000 ethnic Ukrainians living on the eve of the genocide in the Russian Republic (RSFSR).[52][53]

Yaroslav Bilinsky

Yaroslav Bilinsky, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware, writes in the Journal of Genocide Research (1999) in a review of Holodomor literature—he concludes:

Political usage should not override scholarly logic, especially political usage which is just being established in independent Ukraine, arguably seven years late. My argument, however, is that both logic and political usage in Ukraine point in one direction, that of the terror-famine being genocidal. Stalin hated the Ukrainians, as accepted as a fact by Sakharov, revealed in the telegram to Zatonsky and inferred from his polemics with the Yugoslav communist Semich. Stalin decided to collectivize Soviet agriculture and under the cover of collectivization teach the Ukrainians a bloody lesson. Had it not been for Stalinist hubris and the incorporation of the more nationalistically minded and less physically decimated Western Ukrainians after 1939, the Ukrainian nation might have never recovered from the Stalinist offensive against the main army of the Ukrainian national movement, the peasants.[54]

James Mace

American historian James E. Mace wrote:

For the Ukrainians the famine must be understood as the most terrible part of a consistent policy carried out against them: the destruction of their cultural and spiritual elite which began with the trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine, the destruction of the official Ukrainian wing of the Communist Party, and the destruction of their social basis in the countryside. Against them the famine seems to have been designed as part of a campaign to destroy them as a political factor and as a social organism.[55]

Stanislav Kulchytsky

Ukrainian historian Stanislav Kulchytsky has contended that:

[T]he way Stalin dealt with the Ukrainian countryside lifted the events out of the category of merely a famine and into the realm of genocide. In the fall of 1932, on orders from Moscow, government troops came to villages requisitioning grain to meet Stalin’s unrealistic quotas. At gunpoint they took away grain, even when peasants did not have enough for themselves. Those peasants who had no grain were deprived of other food stocks. Those who resisted were shot. Then a Jan. 22nd, 1933 directive from Stalin and Molotov sealed off Ukrainian borders to prevent famished peasants from escaping.[56]

Norman Naimark

According to Norman Naimark, Professor of East European Studies at Stanford University, the Ukrainian killer famine should be considered an act of genocide.[57] He writes:

There is enough evidence - if not overwhelming evidence - to indicate that Stalin and his lieutenants knew that the widespread famine in the USSR in 1932-33 hit Ukraine particularly hard, and that they were ready to see millions of Ukrainian peasants die as a result. They made no efforts to provide relief; they prevented the peasants from seeking food themselves in the cities or elsewhere in the USSR; and they refused to relax restrictions on grain deliveries until it was too late. Stalin's hostility to the Ukrainians and their attempts to maintain their form of "home rule" as well as his anger that Ukrainian peasants resisted collectivization fueled the killer famine.[58]

Mark Tauger and opponents

West Virginia University professor Mark Tauger argued that the 1932 harvest was smaller than the official estimate, and smaller than the harvest of 1933, which would suggest the famine was not "man-made."[59] Tauger's evidence, methodologies and conclusions in regard to the famine were criticized by Robert Davies and Stephen Wheatcroft in their book The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–33, published in 2004.[60][61] Tauger, however, maintains that his harvest estimates are supported by evidence, and his conclusions are shared by a number of other scholars.[60] Historian James Mace wrote that Mark Tauger's argument "is not taken seriously by either Russians or Ukrainians who have studied the topic."[62] David Marples, professor of history at the University of Alberta, was critical of Tauger's claims, stating "Dr. Tauger and other scholars fail to distinguish between shortages, droughts and outright famine. There is no such thing as a "natural" famine, no matter the size of the harvest. A famine requires some form of state or human input."[63]

Steven Rosefielde

Professor Steven Rosefielde argues in his 2009 book Red Holocaust that "Grain supplies were sufficient enough to sustain everyone if properly distributed. People died mostly from terror-starvation (excess grain exports, seizure of edibles from the starving, state refusal to provide emergency relief, bans on outmigration, and forced deportation to food-deficit locales), not poor harvests and routine administrative bungling."[64]

Timothy Snyder

Yale historian Timothy Snyder asserts that the starvation was "deliberate"[65] as several of the most lethal policies applied only, or mostly, to Ukraine.[66] He argues the Soviets themselves "made sure that the term genocide, contrary to Lemkin's intentions, excluded political and economic groups." Thus the Ukrainian famine can be presented as "somehow less genocidal because it targeted a class, kulaks, as well as a nation, Ukraine."[67]

Michael Ellman

Professor Michael Ellman of the University of Amsterdam concludes that "Team-Stalin’s behaviour in 1930–34 clearly constitutes a crime against humanity (or a series of crimes against humanity) as that is defined in the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (...)".[note 1]:681 These include not only policies that exacerbated the starvation (exporting 1.8 million tonnes of grain during the height of the famine, banning migration from famine-stricken areas and refusing to secure humanitarian aid from abroad), but also mass shootings and deportations of alleged "kulaks", "counter-revolutionaries" and other "Anti-Soviet elements" around the same time.[68]:684, 681, 689

However, as to whether "Team-Stalin [was, further,] guilty of genocide",[68]:681 Ellman asserts that if so, "Many other events of the 1917–53 era (e.g. the deportation of whole nationalities, and the 'national operations' of 1937–38) would also qualify as genocide, as would the acts of [many Western countries]."[68]:690–691 Citing three physical elements susceptible also of "non-genocidal interpretations" and two mental elements lacking proof of specific intent that he contends are, taken together, "not unambiguous evidence of genocide", Ellman concludes as to genocide, that were he a juror, he would support a not guilty or "not proven" verdict.[note 2]:686

Ellman asserts that the "national operations" of the NKVD, particularly the "Polish operation", which occurred during the late 1930s during the great purges may qualify as genocide even under the strictest definition, but there has been no ruling on the matter.[68]:663–693

Nicolas Werth

Nicolas Werth, historian and co-author of The Black Book of Communism accepted a line of interpretation developed by Andrea Graziosi, and now believes that the Ukrainian famine of 1932–33 can be defined as a genocide according to the 1948 United Nations Convention:

This specifically anti-Ukrainian assault makes it possible to define the totality of intentional political actions taken from late summer 1932 by the Stalinist regime against the Ukrainian peasantry as genocide. With hunger as its deadly arm, the regime sought to punish and terrorize the peasants, resulting in fatalities exceeding four million people in Ukraine and the northern Caucasus.[69]

Other modern academics

A number of modern academics lean toward the definition of the Holodomor as genocide, echoing Dr Raphael Lemkin's views. Their work is presented in the collection of essays Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Soviet Ukraine, printed in 2008.[70]

Notes

- ↑ "Team-Stalin's behaviour in 1930 – 34 clearly constitutes a crime against humanity (or a series of crimes against humanity) as that is defined in the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court article 7, subsection 1 (d) and (h) and, if the argument of the previous section of this article on national criminal law is accepted, then also subsection 1 (a) of the Statute would apply."[68]

- ↑ "If the present author were a member of the jury trying this case he would support a verdict of not guilty (or possibly the Scottish verdict of not proven). The reasons for this are as follows. First, the three physical elements in the alleged crime can all be given non-genocidal interpretations. Secondly, the two mental elements are not unambiguous evidence of genocide. Suspicion of an ethnic group may lead to genocide, but by itself is not evidence of genocide. Hence it would seem that the necessary proof of specific intent is lacking"[68]

References

- ↑ Robert J. Sternberg; Karin Sternberg (2008). The Nature of Hate. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-89698-6. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ↑ "MEPs recognize Ukraine's famine as crime against humanity". Russian News & Information Agency. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Robert William Davies, Stephen G. Wheatcroft, Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History Palgrave Macmillan (2002) ISBN 978-0-333-75461-0, chapter The Soviet Famine of 1932–33 and the Crisis in Agriculture p. 69 et seq.

- 1 2 3 "Russian lawmakers reject Ukraine's view on Stalin-era famine". Russian News & Information Agency. 2008-04-02.

- 1 2 "Parliament recognises Ukrainian famine of 1930s as crime against humanity". European Parliament. 23 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "The Artificial Famine/Genocide (Holodomor) in Ukraine 1932-33". InfoUkes. 2006-11-28. Updated April 26th 2009. Retrieved 08-12-2013.

- ↑ David Marples (30 November 2005). "The great famine debate goes on...". ExpressNews (University of Alberta), originally published in the Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008.

- ↑ Kuchytsky, Stanislav (17 February 2007). Голодомор 1932 — 1933 гг. как геноцид: пробелы в доказательной базе [Holodomor 1932-1933 as genocide: gaps in the evidence]. Den (in Russian). Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Ukrainian holod (голод, 'hunger', compare Russian golod) should not be confused with kholod (холод, 'cold'). For details, see Romanization of Ukrainian. Mor means 'plague' in the sense of a disastrous evil or affliction, or a sudden unwelcome outbreak. See wikt:plague.

- ↑ Голодомор, in "Velykyi tlumachnyi slovnyk suchasnoi ukrains'koi movy: 170 000 sliv", chief ed. V. T. Busel, Irpin, Perun (2004), ISBN 966-569-013-2

- ↑ Helen Fawkes, "Legacy of famine divides Ukraine," BBC (24 November 2006). Retrieved 08-12-2013.

- ↑ "Holodomor and Holocaust denial to be a criminal offense", 3 April 2007

- ↑ "What the Verkhovna Rada actually passed", February 28, 2007

- ↑ "Public denial of Holodomor Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine as genocide of Ukrainian people to be prosecuted". Radio Ukraine International. 2007-12-10. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03.

- ↑ Interfax-Ukraine (27 April 2010). "Our Ukraine Party: Yanukovych violated law on Holodomor of 1932-1933". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 2012-09-30. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ Bovt, Georgy (2008-04-24). "Equating Holodomor With Genocide". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ "Cable 08BISHKEK1095, CANDID DISCUSSION WITH PRINCE ANDREW ON THE KYRGYZ". WikiLeaks. November 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Statement On Commemorating the Victims of Genocide and Political Repressions Committed in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933" (PDF)., 26th Session of the Baltic Assembly, 13th Baltic Council, from 22 to 24 November 2007, Riga, Latvia, (accessed on December 9, 2007)

- ↑ "Baltic Assembly Adopts Statement "In Commemorating Victims of Genocide and Political Repression in Ukraine in 1932 1933"". Ukrinform. 4 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ "Letter dated 7 November 2003 from the Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General" (PDF). Permanent Mission of Ukraine to the UN. 7 November 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ UN Member-states sign joint declaration on Great Famine

- ↑ "Resolution 1481 (2006) Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes". Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. 25 January 2006. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- ↑ PACE strongly condemns crimes of totalitarian communist regimes, PACE News, (accessed on June 22, 2007)

- ↑ "Doc. 10765 - Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes". Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. 16 December 2005. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ↑ "Holodomor Ucrania proposes a la Asamblea Parlamentaria del Consejo de Europa el condemn Holodomor". UCRANIA.com. 26 January 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ↑ "Joint Statement of the OSCE participating States: Andorra, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Georgia, Germany, Holy See, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States of America "On 75th Anniversary of the Holodomor of 1932 and 1933 in Ukraine"". Madrid: Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original (DOC) on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ "25 OSCE-Participant Countries Adopt Joint Statement "On 75th Anniversary of Holodomor in Ukraine 1932-1933"". Ukrinform. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ "34 C/50: Remembrance of Victims of the Great Famine (Holodomor) in Ukraine" (PDF). UNESCO. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ UNESCO Calls On Its Member-Countries To Honor Memories Of Victims Of 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine, November 1, 2007, Ukrainian News Agency, (reached on November 1, 2007)

- ↑ Mykola Siruk (6 November 2007). "Not too late. Three messages in UNESCO resolution commemorating Holodomor victims". The Day. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ↑ "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomor Education. 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Foreign Affairs: Ukrainian Famine (No. 680)" (PDF). Journals of the Senate. 114: 2652–2653. 30 October 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2004.

- ↑ "Australian Senate condemns Famine-Genocide". The Ukrainian Weekly. LXXI (46). 16 November 2003. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "Journals of the Senate No.72, 2nd Session, 37th Parliament" (PDF). 19 June 2003: 994–995. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Canadian Senate adopts motion on Famine-Genocide, by Peter Stieda, The Ukrainian Weekly, June 29, 2003, No. 26, Vol LXXI, (accessed on June 26, 2007)

- ↑ Colombia Recognizes Holodomor Famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933 The Genocide, Ukrainian News Agency, December 24, 2007, (Accessed on December 26, 2007)

- ↑ "Columbia declares Holodomor an act of genocide". Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. 25 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "Aprueba resolución: Congreso se solidariza con pueblo Ucraniano" [Resolution passed: Congress is in solidarity with Ukrainian people]. National Congress of Ecuador (in Spanish). 30 October 2007. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ↑ Ecuador Recognized Holodomor in Ukraine!, Media International Group, October 31, 2007, (Accessed on October 31, 2007)

- ↑ (Polish) UCHWAŁA, Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, z dnia 6 grudnia 2006 r., w sprawie uczczenia ofiar Wielkiego Głodu na Ukrainie.

- ↑ "Sprawozdanie - Komisji Ustawodawczej oraz Komisji Spraw Zagranicznych - o projekcie uchwały w sprawie rocznicy Wielkiego Głodu na Ukrainie" [Report of the Legislative Committee and Foreign Affairs Committee - on the project resolution concerning the anniversary of the Great Famine in Ukraine] (PDF). Senate of the Republic of Poland (in Polish). 14 March 2006. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomoreducation.org. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ Resolução do Senado da Argentina (n.º1278/03), Resolution of the Senate of Argentina (No. 1278-03), June 26, 2003

- ↑ El proyecto de ley number 1278-03, Ukrainian World Congress (accessed on October 31, 2006)

- ↑ National Senator Carlos Alberto Rossi, Honorable Senate of the Nation, (accessed on February 13, 2007)

- ↑ Argentinean Parliament approved resolution to commemorate 1932 to 1933 Holodomor victims in Ukraine, Ukrinform, December 28, 2007, (accessed on December 28, 2007)

- ↑ "Parlament České republiky, Poslanecká Sněmovna - 535 Usnesení Poslanecké sněmovny z 23. schůze 30. listopadu 2007" [The Parliament of the Czech Republic, Chamber of Deputies - Resolution 535 of Chamber of Deputies from the 23rd meeting of 30 November 2007] (PDF). Parliament of the Czech Republic (in Czech). 30 November 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ "NR SR: Prijali deklaráciu k hladomoru v bývalom Sovietskom zväze" [National Council: Adopted a declaration on the Holodomor in the former Soviet Union] (in Slovak). EpochMedia. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "Slovak Parliament Recognizes Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Former USSR, Including in Ukraine, "Extermination Act". Ukrinform. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ↑ "Holodomor 1932-1933. Reference, Government Reports, Laws.". Connecticut Holodomor Committee. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "Resolution of the House of Representatives of the US (HRES 356 EH)" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. 20 October 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2012.

- ↑ "Guide to Lemkin's papers 1947 to 1959" (PDF). nypl.org. 31 August 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2005.

- ↑ Roman Serbyn, "Excerpts from "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine"," Ukrainian Independent Information Agency, unian.info (07.10.2008). Retrieved 08-12-2013.

- ↑ Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999). "Was the Ukrainian Famine of 1932-1933 Genocide?". Journal of Genocide Research. faminegenocide.com. 1 (2): 147–156. doi:10.1080/14623529908413948. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ↑ Mace, J. E. (1986) "The man-made famine of 1933 in Soviet Ukraine," p 12; in R. Serbyn and B. Krawchenko, eds, Famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933 (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta).

- ↑ Andriy J. Semotiuk (5 June 2008). "Evidence proves genocide occurred". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ↑ Roman Szporluk (2012). "Commentary on 'Stalin's Genocides'". Journal of Cold War Studies. muse.jhu.edu. pp. 175–179. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2010. pp. 134-135. ISBN 0-691-14784-1

- ↑ Tauger, Mark B. (1991). "The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933" (PDF). Slavic Review. 50 (1): 70–89. doi:10.2307/2500600. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- 1 2 Tauger, Mark B. Arguing from errors: On certain issues in Robert Davies' and Stephen Wheatcroft's analysis of the 1932 Soviet grain harvest and the Great Soviet famine of 1931-1933, Europe-Asia Studies, 2006, 58:6, p. 975

- ↑ Wheatcroft, S. G. Towards explaining Soviet famine of 1931-3: Political and natural factors in perspective, Food and Foodways, 2004, 12:2, 107-136.

- ↑ James Mace, Intellectual Europe on Ukrainian Genocide, The Day, October 21, 2003

- ↑ Dr. David Marples, "Analysis: Debating the undebatable? Ukraine Famine of 1932-1933," The Ukrainian Weekly, July 14, 2002, No. 28, Vol. LXX. Retrieved 08-12-2013.

- ↑ Steven Rosefielde. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7 pg. 259

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 0-465-00239-0 p. vii

- ↑ Timothy Snyder. (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, pp42-46

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 0-465-00239-0 p. 413

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ellman, Michael (June 2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33 Revisited" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. Routledge. 59 (4). doi:10.1080/09668130701291899. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ Nicolas Werth (18 April 2008). "Case Study: The Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933". Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. ISSN 1961-9898. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Lubomyr Y. Luciuk; Lisa Grekul (2008). Holodomor: reflections on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kashtan Press. ISBN 978-1-896354-33-0. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

External links

- Documentary about the Holodomor, called Genocide Revealed (2011); preview available here (In Ukrainian)