Vietnamese phonology

This article is a technical description of the sound system of the Vietnamese language, including phonetics and phonology. Two main varieties of Vietnamese, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, are described below.

Initial consonants

Initial consonants which exist only in the Hanoi dialect are in red, while those that exist only in the Saigon dialect are in blue.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Stop/ Affricate |

plain | (p) | t | ʈʂ | c | k | (ʔ) |

| aspirated | tʰ | ||||||

| glottalized | ɓ | ɗ | |||||

| Fricative | plain | f | s | ʂ | x | h | |

| voiced | v | z | ʐ | c | |||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||

- /p/ occurs syllable-initially only in loan words, and is mostly converted into /ɓ/ (as in sâm banh, derived from French champagne).

- /m, ɓ/ are bilabial, while /f, v/ are labiodental.

- The glottalized stops are preglottalized and voiced: [ʔɓ, ʔɗ] (i.e., the glottis is always closed before the oral closure). This glottal closure is often not released before the release of the oral closure, resulting in the characteristic implosive pronunciation. However, sometimes the glottal closure is released prior to the oral release in which case the stops are pronounced [ʔb, ʔd]. Therefore, the primary characteristic is preglottalization with implosion being secondary.

- /tʰ, t/ are denti-alveolar ([t̪ʰ, t̪]), while /ɗ, n/ are apico-alveolar.[1]

- /c, ɲ/ are phonetically lamino-palatoalveolar (i.e. the blade of the tongue makes contact behind the alveolar ridge).

- /c/ is often slightly affricated [t͡ɕ], but it is unaspirated. (Note that the English affricate is aspirated [t͡ʃʰ] and usually apical, unlike Vietnamese).

- A glottal stop [ʔ] is inserted before words that begin with a vowel, and additionally before /w/ in the Hanoian dialect:

ăn 'to eat' /ăn/ → [ʔăn] uỷ 'to delegate' /wi/ → [ʔwi]

Hanoi

- /ʐ/ and /j/ exist only in loan words.

- /s, z/ are dentalized laminal alveolar: [s̪, z̪].[2]

- /l/ is apico-alveolar.[1]

- /w/ can form consonant clusters with other consonants except labial consonants.

Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon)

- /v/ is generally pronounced [j] in informal speech, but the speakers generally pronounce [v] when they read a text. It is always pronounced [v] in loan words (va li, ti vi etc.), even in informal speech. There is [vj, bj, βj] that is also present among other speakers. These pronunciations are remnants of a merger and sound change involving /v/ in southern speech (but /v/ is always present in the northern and central regions).

- Some speakers don't distinguish /s/ and /ʂ/.

- Some speakers don't distinguish /c/ and /tʂ/.

- Some speakers pronounce d as [j], and gi as [z], many speakers pronounce both as [j].

- /s/ is apico-alveolar.[2]

- /l/ is lamino-palatoalveolar: [lʲ].[2]

- In southern speech, the phoneme /ʐ/ has a number of variant pronunciations that depend on the speaker. More than one pronunciation may even be found within a single speaker. It may occur as a retroflex fricative [ʐ], an alveolar approximant [ɹ], a flap [ɾ], a trill [r], or a fricative tap/trill [ɾ̞, r̝]. This sound is generally represented in Vietnamese linguistics by the letter ⟨r⟩.

- /w/ cannot form consonant clusters.

- /kw/ is pronounced /ɡw/ or simply /w/.

Reduction of consonant clusters

In the Saigonese dialect, all initial consonant + /w/ clusters have been reduced:[3]

- After velars and glottals (except /c/ and /x/), the velar is dropped:

hu /hw/ → u /w/ qu /kw/ → u /w/ ngu /ŋw/ → u /w/

Comparison of initials

In Hanoian Vietnamese, d, gi and r are all pronounced /z/, while x and s are both pronounced /s/. The table below summarizes these sound correspondences:

Syllable onsets Hanoi Saigon Example word Hanoi Saigon /v/ /j/ vợ 'wife' /və˨˩ˀ/ /və˨˧/ or /jə˨˧/ /z/ da 'skin' /za˧/ /ja˧/ gia 'to add' /za˧/ or /ja˧/ /ʐ/ ra 'to go out' /ʐa˧/ /c/ /c/ chẻ 'split' /cɛ˧˩/ /cɛ˩˥/ /tʂ/ trẻ 'young' /tʂɛ˩˥/ /s/ /s/ xinh 'beautiful' /siŋ˧/ /sɨn˧/ /ʂ/ sinh 'born' /ʂɨn˧/

Vowels

Vowel nuclei

Front Central Back Centering /iə̯/ ⟨ia~iê⟩ /ɨə̯/ ⟨ưa~ươ⟩ /uə̯/ ⟨ua~uô⟩ Close /i/ ⟨i, y⟩ /ɨ/ ⟨ư⟩ /u/ ⟨u⟩ Mid /e/ ⟨ê⟩ /ə/ ⟨ơ⟩

/ə̆/ ⟨â⟩/o/ ⟨ô⟩ Open /ɛ/ ⟨e⟩ /a/ ⟨a⟩

/ă/ ⟨ă⟩/ɔ/ ⟨o⟩

The IPA chart of vowel nuclei to the right is based on the sounds in Hanoi Vietnamese, (i.e., other regions of Vietnam may have different inventories). Vowel nuclei consist of monophthongs (i.e., simple vowels) and three centering diphthongs.

- All vowels are unrounded except for the three back rounded vowels: /u, o, ɔ/.

- /ə̆/ and /ă/ are pronounced short — shorter than the other vowels.

- While there are small spectral differences between /ə̆/ and /ə/, it has not been established that they are perceptually significant.[4]

- /ɨ/: Many descriptions, such as Thompson,[2] Nguyễn (1970), Nguyễn (1997), consider this vowel to be close back unrounded: [ɯ]. However, Han's[5] instrumental analysis indicates that it is more central than back. Hoang (1965), Brunelle (2003) and Phạm (2006) also transcribe this vowel as central.

- According to Hoang (1965), /ə, ə̆, a/ are phonetically central [ɘ, ɐ, ä], whereas /ă/ is back [ɑ].[6]

- The vowels /i, u, ɨ/ become [ɪ, ʊ, ɪ̈] before /k, ŋ/: lịch /lik˩/ → [lɪk˩], chúc /cuk˧˥/ → [cʊk˧˥], thức /tʰɨk˧˥/ → [tʰɪ̈k˧˥] etc.

- Thompson (1965) notes that in Hanoi the diphthongs, iê /iə̯/, ươ /ɨə̯/, uô /uə̯/, may be pronounced [ie̯, ɨə̯, uo̯], respectively (as the spelling suggests), but before /k, ŋ/ and in open syllables these are always pronounced [iə, ɨə, uə].

- In Southern Vietnamese, the high and upper-mid vowels /i, ɨ, u, e, ə, o/ are diphthongized in open syllables: [ɪi̯, ɪ̈ɨ̯, ʊu̯, ɛe̯, ɜɘ̯, ɔo̯]:

- {| cellpadding="4" style="line-height: 1.0em;"

| chị | ('elder sister') | /ci/ | → | [cɪi̯] | | quê | ('countryside') | /we/ | → | [wɛe̯] |- | tư | ('fourth') | /tɨ/ | → | [tɪ̈ɨ̯] | | mơ | ('to dream') | /mə/ | → | [mɜɘ̯] |- | thu | ('autumn') | /tʰu/ | → | [tʰʊu̯] | | cô | ('paternal aunt') | /ko/ | → | [kɔo̯]

|}

Closing sequences

In Vietnamese, vowel nuclei are able to combine with offglides /j/ or /w/ to form closing diphthongs and triphthongs. Below is a chart[7] listing the closing sequences of general northern speech.

/w/ offglide /j/ offglide Front Central Back Centering /iə̯w/ ⟨iêu⟩ /ɨə̯w/ ⟨ươu⟩ /ɨə̯j/ ⟨ươi⟩ /uə̯j/ ⟨uôi⟩ Close /iw/ ⟨iu⟩ /hw/ ⟨ưu⟩ /ɨj/ ⟨ưi⟩ /uj/ ⟨ui⟩ Mid /ew/ ⟨êu⟩ –

/ə̆w/ ⟨âu⟩/əj/ ⟨ơi⟩

/ə̆j/ ⟨ây⟩/oj/ ⟨ôi⟩ Open /ɛw/ ⟨eo⟩ /ɡw/ ⟨ao⟩

/ăw/ ⟨au⟩/aj/ ⟨ai⟩

/ăj/ ⟨ay⟩/ɔj/ ⟨oi⟩

Thompson (1965) says that in Hanoi, words spelled with ưu and ươu are pronounced /iw, iəw/, respectively, whereas other dialects in the Tonkin delta pronounce them as /hw/ and /ɨəw/. Hanoi speakers that do pronounce these words with /hw/ and /ɨəw/ are using only a spelling pronunciation.

Final stops

When stops /p, t, k/ occur at the end of words, they have no audible release ([p̚, t̚, k̚]):

đáp 'to reply' /ɗap/ → [ɗap̚] mát 'cool' /mat/ → [mat̚] khác 'different' /xak/ → [xak̚]

When the velar consonants /k, ŋ/ are after /u/, /ɔ/ and /o/, they are articulated with a simultaneous bilabial closure [k͡p̚, ŋ͡m] (i.e. doubly articulated) or are strongly labialized [kʷ̚, ŋʷ].

đọc 'to read' /ɗɔk/ → [ɗău̯k͡p̚], [ɗău̯kʷ̚] độc 'poison' /ɗok/ → [ɗə̆u̯k͡p̚], [ɗə̆u̯kʷ̚] đục 'muddy' /ɗuk/ → [ɗʊk͡p̚], [ɗʊkʷ̚] phòng 'room' /fɔŋ/ → [fău̯ŋ͡m], [fău̯ŋʷ] ông 'man' /oŋ/ → [ə̆u̯ŋ͡m], [ə̆u̯ŋʷ] ung 'cancer' /uŋ/ → [ʔʊŋ͡m], [ʔʊŋʷ]

Hanoi finals

Vietnamese rimes ending with velar consonants have been diphthongized in the Hanoian dialect:[8]

ong, oc /ɔŋ/, /ɔk/ → [ău̯ŋ͡m], [ău̯k͡p̚] ông, ôc /oŋ/, /ok/ → [ə̆u̯ŋ͡m], [ə̆u̯k͡p̚] anh, ach /ɛŋ/, /ɛk/ → [ăi̯ŋ], [ăi̯k̚] ênh, êch /eŋ/, /ek/ → [ə̆i̯ŋ], [ə̆i̯k̚]

The monophthongal variants are now mainly heard in the Nghệ An, Hà Tĩnh ([ɔːŋ], [ɔːk], [oːŋ], [oːk]) and a few South Central Coast dialects ([eːŋ], [eːk]), and have been diphthongized in most Northern and Southern varieties (not to be confused with the palatalized recognitions of on [ɔːŋ], ot [ɔːk], ôn [oːŋ], ôt [oːk] in Southern varieties).

Analysis of final ch, nh

The pronunciation of syllable-final ch and nh in Hanoi Vietnamese has had different analyses. One analysis, that of Thompson (1965) has them as being phonemes /c, ɲ/, where /c/ contrasts with both syllable-final t /t/ and c /k/ and /ɲ/ contrasts with syllable-final n /n/ and ng /ŋ/. Final /c, ɲ/ is, then, identified with syllable-initial /c, ɲ/.

Another analysis has final ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨nh⟩ as representing predictable allophonic variants of the velar phonemes /k/ and /ŋ/ that occur after upper front vowels /i/ (orthographic ⟨i⟩) and /e/ (orthographic ⟨ê⟩). This analysis interprets orthographic ⟨ach⟩ and ⟨anh⟩ as an underlying /ɛ/, which becomes phonetically open and diphthongized: /ɛk/ → [ăi̯k̟], /ɛŋ/ → [ăi̯ŋ̟].[9]

Arguments for the second analysis include the limited distribution of final [c] and [r], the gap in the distribution of [k] and [ŋ] which do not occur after [i] and [e], the pronunciation of ⟨ach⟩ and ⟨anh⟩ as [ɛc] and [ɛɲ] in certain conservative central dialects,[8] and the patterning of [k]~[c] and [ŋ]~[r] in certain reduplicated words. Additionally, final [c] is not usually articulated as far forward as the initial [c]: [c] and [r] are pre-velar [k̟, ŋ̟].

The first analysis closely follows the surface pronunciation of a slightly different Hanoi dialect than the second. In this dialect, the /a/ in /ac/ and /aɲ/ is not diphthongized but is actually articulated more forward, approaching a front vowel [æ]. This results in a three-way contrast between the rimes ăn [æ̈n] vs. anh [æ̈ɲ] vs. ăng [æ̈ŋ]. For this reason, a separate phonemic /ɲ/ is posited.

Saigon finals

While the variety of Vietnamese spoken in Hanoi has preserved finals faithfully from old Vietnamese, the variety spoken in Saigon has drastically changed its finals. There were two steps in the development of rimes in the Saigonese dialect from old Vietnamese. In the first step, -ch and -nh merged with -t and -n, while rimes ending in /t, n/ (except after /i, e/) merged with /k, ŋ/. In the second step, vowels in alveolar rimes became centralized,[10] analogous to the diphthongization in the Hanoian dialect.

Comparison of finals

Below is a table of rimes ending in /n, t, ŋ, k/ for the Hanoian dialect:

| /ă/ | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ɔ/ | /ə̆/ | /ə/ | /e/ | /o/ | /i/ | /ɨ/ | /u/ | /iə̯/ | /ɨə̯/ | /uə̯/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /n/ | ăn | an | en | on | ân | ơn | ên | ôn | in | ưn | un | iên | ươn | uôn |

| /t/ | ăt | at | et | ot | ât | ơt | êt | ôt | it | ưt | ut | iêt | ươt | uôt |

| /ŋ/ | ăng | ang | anh | ong | âng | – | ênh | ông | inh | ưng | ung | iêng | ương | uông |

| /k/ | ăc | ac | ach | oc | âc | – | êch | ôc | ich | ưc | uc | iêc | ươc | uôc |

In the Saigonese dialect, /k, ŋ/ merged with /t, n/ after /i, e, ɛ/, and vice versa in the rest of the cases:

| /ă/ | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ɔ/ | /ə̆/ | /ə/ | /e/ | /o/ | /i/ | /ɨ/ | /u/ | /iə̯/ | /ɨə̯/ | /uə̯/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /n/ | en

anh |

ên

ênh |

in

inh |

|||||||||||

| /t/ | et

ach |

êt

êch |

it

ich |

|||||||||||

| /ŋ/ | ăn

ăng |

an

ang |

on

ong |

ân

âng |

ơn

– |

ôn

ông |

ưn

ưng |

un

ung |

iên

iêng |

ươn

ương |

uôn

uông | |||

| /k/ | ăt

ăc |

at

ac |

ot

oc |

ât

âc |

ơt

– |

ôt

ôc |

ưt

ưc |

ut

uc |

iêt

iêc |

ươt

ươc |

uôt

uôc |

Note: Combinations that changed their pronunciation due to merger are bolded.

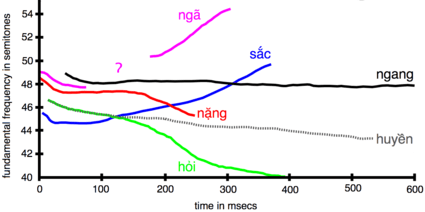

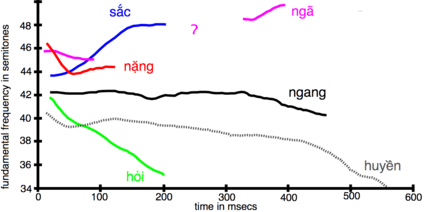

Tone

Vietnamese vowels are all pronounced with an inherent tone. Tones differ in

- pitch

- length

- contour melody

- intensity

- phonation (with or without accompanying constricted vocal cords)

Unlike many Native American, African, and Chinese languages, Vietnamese tones do not rely solely on pitch contour. Vietnamese often uses instead a register complex (which is a combination of phonation type, pitch, length, vowel quality, etc.). So perhaps a better description would be that Vietnamese is a register language and not a "pure" tonal language.[11]

In Vietnamese orthography, tone is indicated by diacritics written above or below the vowel.

Six-tone analysis

There is much variation among speakers concerning how tone is realized phonetically. There are differences between varieties of Vietnamese spoken in the major geographic areas (i.e. northern, central, southern) and smaller differences within the major areas (e.g. Hanoi vs. other northern varieties). In addition, there seems to be variation among individuals. More research is needed to determine the remaining details of tone realization and the variation among speakers.

Northern varieties

The six tones in the Hanoi and other northern varieties are:

Tone name Tone ID Description Chao Tone Contour Diacritic Example ngang "level" A1 mid level ˧ (33) (no mark) ba ('three') huyền "hanging" A2 low falling (breathy) ˨˩ (21) or (31) ` bà ('lady') sắc "sharp" B1 mid rising, tense ˧˥ (35) ´ bá ('governor') nặng "heavy" B2 mid falling, glottalized, short ˧ˀ˨ʔ (3ˀ2ʔ) or ˧ˀ˩ʔ (3ˀ1ʔ) ̣ bạ ('at random') hỏi "asking" C1 mid falling(-rising), harsh ˧˩˧ (313) or (323) or (31) ̉ bả ('poison') ngã "tumbling" C2 mid rising, glottalized ˧ˀ˥ (3ˀ5) or (4ˀ5) ˜ bã ('residue')

Ngang tone:

- The ngang tone is level at around the mid level (33) and is produced with modal voice phonation (i.e. with "normal" phonation). Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "level"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "high (or mid) level".

Huyền tone:

- The huyền tone starts low-mid and falls (21). Some Hanoi speakers start at a somewhat higher point (31). It is sometimes accompanied by breathy voice (or lax) phonation in some speakers, but this is lacking in other speakers: bà = [ɓa˨˩].[12] Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "grave-lowering"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "low falling".

Hỏi tone:

- The hỏi tone starts a mid level and falls. It starts with modal voice phonation, which moves increasingly toward tense voice with accompanying harsh voice (although the harsh voice seems to vary according to speaker). In Hanoi, the tone is mid falling (31). In other northern speakers, the tone is mid falling and then rises back to the mid level (313 or 323). This characteristic gives this tone its traditional description as "dipping". However, the falling-rising contour is most obvious in citation forms or when syllable-final; in other positions and when in fast speech, the rising contour is negligible. The hỏi also is relatively short compared with the other tones, but not as short as the nặng tone. Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "smooth-rising"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "dipping-rising".

Ngã tone:

- The ngã tone is mid rising (35). Many speakers begin the vowel with modal voice, followed by strong creaky voice starting toward the middle of the vowel, which is then lessening as the end of the syllable is approached. Some speakers with more dramatic glottalization have a glottal stop closure in the middle of the vowel (i.e. as [VʔV]). In Hanoi Vietnamese, the tone starts at a higher pitch (45) than other northern speakers. Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "chesty-raised"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "creaking-rising".

Sắc tone:

- The sắc tone starts as mid and then rises (35) in much the same way as the ngã tone. It is accompanied by tense voice phonation throughout the duration of the vowel. In some Hanoi speakers, the ngã tone is noticeably higher than the sắc tone, for example: sắc = ˧˦ (34); ngã = ˦ˀ˥ (45). Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "acute-angry"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "high (or mid) rising".

Nặng tone:

- The nặng tone starts mid or low-mid and rapidly falls in pitch (32 or 21). It starts with tense voice that becomes increasingly tense until the vowel ends in a glottal stop closure. This tone is noticeably shorter than the other tones. Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) describes this as "chesty-heavy"; Nguyễn (1997) describes it as "constricted".

Southern varieties

The Southern variety is similar through all tones except for the nặng tone, which is pronounced [˨˧]. Many of those speaking Southern dialects will omit using the ngã tone and replace it with the hỏi tone.

North-central and Central varieties

North-central and Central Vietnamese varieties are fairly similar with respect to tone although within the North-central dialect region there is considerable internal variation.

It is sometimes said (by people from other provinces) that people from Nghệ An pronounce every tone as a nặng tone.

Eight-tone analysis

An older analysis assumes eight tones rather than six.[13] This follows the lead of traditional Chinese phonology. In Middle Chinese, normal syllables allowed for three tonal distinctions, but syllables ending with /p/, /t/ or /k/ had no tonal distinctions. Rather, they were consistently pronounced with in a short high tone, which was called the entering tone and considered a fourth tone. Similar considerations lead to the identification of two additional tones in Vietnamese for syllables ending in /p/, /t/ and /k/. These are not phonemically distinct, however, and hence not considered as separate tones by modern linguists.

Syllables and phonotactics

According to Hannas (1997), there are 4,500 to 4,800 possible spoken syllables (depending on dialect), and the standard national orthography (Quốc Ngữ) can represent 6,200 syllables (Quốc Ngữ orthography represents more phonemic distinctions than are made by any one dialect).[14] A description of syllable structure and exploration of its patterning according to the Prosodic Analysis approach of J.R. Firth is given in Henderson (1966).[15]

The Vietnamese syllable structure follows the scheme:

- Hanoi: (C1)(w)V(G|C2)+T

- Saigon: (C1)V(G|C2)+T

where

- C1 = initial consonant onset

- w = labiovelar on-glide /w/

- V = vowel nucleus

- G = off-glide coda (/j/ or /w/)

- C2 = final consonant coda

- T = tone.

In other words, a syllable can have an optional consonant onset, an optional on-glide /w/ (Hanoi only), and an optional coda. The vowel nucleus may have an additional off-glide.

More explicitly, the syllable types are as follows:

Syllable Example Syllable Example V ê "eh" wV uể "sluggish" VC ám "possess (by ghosts,.etc)" wVC oán "bear a grudge" VC ớt "capsicum" wVC oắt "little imp" CV nữ "female" CwV huỷ "cancel" CVC cơm "rice" CwVC toán "math" CVC tức "angry" CwVC hoặc "or"

C1:

Any consonant may occur in as an onset with the following exceptions:

- /p/ does not occur in native Vietnamese words

w:

- does not occur after labial consonants /ɓ, f, v, m, w/

- does not occur after /n/ in native Vietnamese words (it occurs in uncommon Sino-Vietnamese borrowings)

- absent in Saigonese as Saigonese /w/ behaves as an initial consonant

V:

The vowel nucleus V may be any of the following 14 monophthongs or diphthongs: /i, ɨ, u, e, ə, o, ɛ, ə̆, ɔ, ă, a, iə̯, ɨə̯, uə̯/.

G: The offglide may be /j/ or /w/. Together, V and G must form one of the diphthongs or triphthongs listed in the section on Vowels. The offglide cannot be /w/ if the syllable contains a /w/ onglide, except for case of 'khuỷu (tay)' (elbow).

C2:

The optional coda C2 is restricted to labial, coronal, & velar stops /p, t, k/ and nasals /m, n, ŋ/.

T:

Syllables are spoken with an inherent tone contour. All tone contours are possible for open syllables (syllables without consonant codas) and closed syllables with nasal codas. If the syllable is closed with labial, coronal, or velar stops /p, t, k/, only 2 contours are possible, that is the sắc and the nặng tone.

| Zero coda | Off-glide coda | Nasal consonant coda | Stop consonant coda | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | /j/ | /w/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /t/ | /c/ | /k/ | ||

| Vowel nucleus | /ă/ | ạy [ăj] | ạu [ăw] | ặm [ăm] | ặn [ăn] | ạnh [ăɲ] | ặng [ăŋ] | ặp [ăp] | ặt [ăt] | ạch [ăc] | ặc [ăk] | |

| /a/ | ạ, (gi)à, (gi)ả, (gi)ã, (gi)á [a] | ại [aj] | ạo [aw] | ạm [am] | ạn [an] | ạng [aŋ] | ạp [ap] | ạt [at] | ạc [ak] | |||

| /ɛ/ | ẹ [ɛ] | ẹo [ɛw] | ẹm [ɛm] | ẹn [ɛn] | ẹng [ɛŋ] | ẹp [ɛp] | ẹt [ɛt] | ẹc [ɛk] | ||||

| /ɔ/ | ọ [ɔ] | ọi [ɔj] | ọm [ɔm] | ọn [ɔn] | ọng, oọng [ɔŋ] | ọp [ɔp] | ọt [ɔt] | ọc, oọc [ɔk] | ||||

| /ə̆/ | ậy [ə̆j] | ậu [ə̆w] | ậm [ə̆m] | ận [ə̆n] | ậng [ə̆ŋ] | ập [ə̆p] | ật [ə̆t] | ậc [ə̆k] | ||||

| /ə/ | ợ [ə] | ợi [əj] | ợm [əm] | ợn [ən] | ợp [əp] | ợt [ət] | ||||||

| /e/ | ệ [e] | ệu [ew] | ệm [em] | ện [en] | ệnh [??] | ệp [ep] | ệt [et] | ệch [??] | ||||

| /o/ | ộ [o] | ội [oj] | ộm [om] | ộn [on] | ộng, ôộng [oŋ] | ộp [op] | ột [ot] | ộc, ôộc [ok] | ||||

| /i/ | ị, ỵ [i] | ịu [iw] | ịm, ỵm [im] | ịn [in] | ịnh [ɪɲ] | ịp, ỵp [ip] | ịt [it] | ịch, ỵch [ɪc] | ||||

| /ɨ/ | ự [ɨ] | ựi [ɨj] | ựu [ɨw] | ựng [ɪ̈ŋ] | ựt [ɨt] | ực [ɪ̈k] | ||||||

| /u/ | ụ [u] | ụi [uj] | ụm [um] | ụn [un] | ụng [ʊŋ] | ụp [up] | ụt [ut] | ục [ʊk] | ||||

| /iə/ | ịa, (g)ịa, yạ [iə] | iệu, yệu [iəw] | iệm, yệm [iəm] | iện, yện [iən] | iệng, yệng [iəŋ] | iệp, yệp [iəp] | iệt, yệt [iət] | iệc [iək] | ||||

| /ɨə/ | ựa [ɨə] | ượi [ɨəj] | ượu [ɨəw] | ượm [ɨəm] | ượn [ɨən] | ượng [ɨəŋ] | ượp [ɨəp] | ượt [ɨət] | ược [ɨək] | |||

| /uə/ | ụa [uə] | uội [uəj] | uộm [uəm] | uộn [uən] | uộng [uəŋ] | uột [uət] | uộc [uək] | |||||

| Labiovelar on-glide followed by vowel nucleus | /ʷă/ | oạy, (q)uạy [ʷăj] | oặm, (q)uặm [ʷăm] | oặn, (q)uặn [ʷăn] | oạnh, (q)uạnh [ʷăɲ] | oặng, (q)uặng [ʷăŋ] | oặp, (q)uặp [ʷăp] | oặt, (q)uặt [ʷăt] | oạch, (q)uạch [ʷăc] | oặc, (q)uặc [ʷăk] | ||

| /ʷa/ | oạ, (q)uạ [ʷa] | oại, (q)uại [ʷaj] | oạo, (q)uạo [ʷaw] | oạm, (q)uạm [ʷam] | oạn, (q)uạn [ʷan] | oạng, (q)uạng [ʷaŋ] | oạp, (q)uạp [ʷap] | oạt, (q)uạt [ʷat] | oạc, (q)uạc [ʷak] | |||

| /ʷɛ/ | oẹ, (q)uẹ [ʷɛ] | oẹo, (q)uẹo [ʷɛw] | oẹm, (q)uẹm [ʷɛm] | oẹn, (q)uẹn [ʷɛn] | oẹng, (q)uẹng [ʷɛŋ] | oẹt, (q)uẹt [ʷɛt] | ||||||

| /ʷə̆/ | uậy [ʷə̆j] | uận [ʷə̆n] | uậng [ʷə̆ŋ] | uật [ʷə̆t] | ||||||||

| /ʷə/ | uợ [ʷə] | |||||||||||

| /ʷe/ | uệ [ʷe] | uệu [ʷew] | uện [ʷen] | uệnh [??] | uệt [ʷet] | uệch [??] | ||||||

| /ʷo/ | uội [ʷoj] | uộm [ʷom] | uộn [ʷon] | uộng [ʷoŋ] | uột [ʷot] | uộc [ʷok] | ||||||

| /ʷi/ | uỵ [ʷi] | uỵu [ʷiw] | uỵn [ʷin] | uỵnh [ʷɪɲ] | uỵp [ʷip] | uỵt [ʷit] | uỵch [ʷɪc] | |||||

| /ʷiə/ | uỵa [ʷiə] | uyện [ʷiən] | uyệt [ʷiət] | |||||||||

| Tone | a /a/, à /â/, á /ǎ/, ả /a᷉/, ã /ǎˀ/, ạ /âˀ/ | á /á/, ạ /à/ | ||||||||||

- Less common rimes may not be represented in this table.

- The nặng tone mark (dot below) has been added to all rimes in this table for illustration purposes only. It indicates which letter tone marks in general are added to, largely according to the "new style" rules of Vietnamese orthography as stated in Quy tắc đặt dấu thanh trong chữ quốc ngữ. In practice, not all these rimes have real words or syllables that have the nặng tone.

- The IPA representations are based on Wikipedia's conventions. Different dialects may have different pronunciations.

Notes

Below is a table comparing four linguists' different transcriptions of Vietnamese vowels as well as the orthographic representation. Notice that this article mostly follows Han (1966), with the exception of marking short vowels short.

comparison of orthography & vowel descriptions Orthography Wikipedia Thompson[2] Han[5] Nguyễn[16] Đoàn[17] i/y i iː i i i ê e eː e e e e ɛ ɛː ɛ a ɛ ư ɨ ɯː ɨ ɯ ɯ u u uː u u u ô ɯ ɯː ɯ ɯ ɯ o ɔ ɔː ɔ ɔ ɔ ơ ə ɤː ɜː əː ɤː â ə̆ ʌ ɜ ə ɤ a a æː ɐː ɐː aː ă ă ɐ ɐ ɐ a

Thompson (1965) says that the vowels [ʌ] (orthographic â) and [ɐ] (orthographic ă) are shorter than all of the other vowels, which is shown here with the length mark [ː] added to the other vowels. His vowels above are only the basic vowel phonemes. Thompson gives a very detailed description of each vowel's various allophonic realizations.

Han (1966) uses acoustic analysis, including spectrograms and formant measuring and plotting, to describe the vowels. She states that the primary difference between orthographic ơ & â and a & ă is a difference of length (a ratio of 2:1). ơ = /ɜː/, â = /ɜ/; a = /ɐː/, ă = /ɐ/. Her formant plots also seem to show that /ɜː/ may be slightly higher than /ɜ/ in some contexts (but this would be secondary to the main difference of length).

Another thing to mention about Han's studies is that she uses a rather small number of participants and, additionally, although her participants are native speakers of the Hanoi variety, they all have lived outside of Hanoi for a significant period of their lives (i.e. in France or Ho Chi Minh City).

Nguyễn (1997) has a simpler, more symmetrical description. He says that his work is not a "complete grammar" but rather a "descriptive introduction." So, his chart above is more a phonological vowel chart rather than a phonetic one.

References

- 1 2 Kirby (2011:382)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thompson (1965)

- ↑ Phạm, Andrea Hòa (2009), "The identity of non-identified sounds: glottal stop, prevocalic /w/ and triphthongs in Vietnamese", Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics, 34

- ↑ Kirby (2011:384)

- 1 2 Han (1966)

- ↑ Hoang (1965:24)

- ↑ From Nguyễn (1997)

- 1 2 Phạm (2006)

- ↑ Although there are some words where orthographic ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ng⟩ occur after /ɛ/, these words are few and are mostly loanwords or onomatopoeia

- ↑ Phạm, Andrea Hòa (2013), "Synchronic evidence for historical hypothesis – Vietnamese palatals", Linguistic Association of Canada and the United States Forum, 39

- ↑ Phạm (2003:93)

- ↑ For example, Nguyễn & Edmondson (1998) show a male speaker from Nam Định with lax voice and a female speaker from Hanoi with breathy voice for the huyền tone while another male speaker from Hanoi has modal voice for the huyền.

- ↑ Phạm (2003:45)

- ↑ Hannas (1997:88)

- ↑ Henderson (1966)

- ↑ Nguyễn (1997)

- ↑ Đoàn (1980)

Bibliography

- Alves, Mark J. 2007. "A Look At North-Central Vietnamese." In SEALS XII Papers from the 12th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2002, edited by Ratree Wayland et al.. Canberra, Australia, 1–7. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University.

- Brunelle, Marc (2003), "Coarticulation effects in northern Vietnamese tones" (PDF), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of Phonetic Sciences

- Brunelle, Marc (2009), "Tone perception in Northern and Southern Vietnamese", Journal of Phonetics, 37 (1): 79–96, doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2008.09.003

- Đoàn, Thiện Thuật (1980), Ngữ âm tiếng Việt, Hà Nội: Đại học và Trung học Chuyên nghiệp

- Đoàn, Thiện Thuật; Nguyễn, Khánh Hà, Phạm, Như Quỳnh. (2003). A Concise Vietnamese Grammar (For Non-Native Speakers). Hà Nội: Thế Giới Publishers, 2001.

- Earle, M. A. (1975). An acoustic study of northern Vietnamese tones. Santa Barbara: Speech Communications Research Laboratory, Inc.

- Ferlus, Michel. (1997). Problemes de la formation du systeme vocalique du vietnamien. Asie Orientale, 26 (1), .

- Gregerson, Kenneth J. (1969). A study of Middle Vietnamese phonology. Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, 44, 135–193. (Published version of the author's MA thesis, University of Washington). (Reprinted 1981, Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics).

- Han, Mieko (1966), Vietnamese vowels, Studies in the phonology of Asian languages, 4, Los Angeles: Acoustic Phonetics Research Laboratory: University of Southern California

- Han, Mieko S. (1968). Complex syllable nuclei in Vietnamese. Studies in the phonology of Asian languages (Vol. 6); U.S. Office of Naval Research. Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

- Han, Mieko S. (1969). Vietnamese tones. Studies in the phonology of Asian languages (Vol. 8). Los Angeles: Acoustic Phonetics Research Laboratory, University of Southern California.

- Han, Mieko S.; & Kim, Kong-On. (1972). Intertonal influences in two-syllable utterances of Vietnamese. Studies in the phonology of Asian languages (Vol. 10). Los Angeles: Acoustic Phonetics Research Laboratory, University of Southern California.

- Han, Mieko S.; & Kim, Kong-On. (1974). Phonetic variation of Vietnamese tones in disyllabic utterances. Journal of Phonetics, 2, 223–232.

- Hannas, William (1997), Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaii Press

- Haudricourt, André-Georges. (1949). Origine des particularités de l'alphabet vietnamien. Dân Việt-Nam, 3, 61–68.

- Haudricourt, André-Georges. (1954). De l'origine des tons en vietnamien. Journal Asiatique, 142 (1).

- Haupers, Ralph. (1969). A note on Vietnamese kh and ph. Mon-Khmer Studies, 3, 76.

- Henderson, Eugénie J. A. 1966. Towards a prosodic statement of the Vietnamese syllable structure. In Memory of J. R. Firth, ed. by C. J. Bazell et al., (pp. 163–197). London: Longmans.

- Hoàng, Thị Châu. (1989). Tiếng Việt trên các miền đất nước: Phương ngữ học. Hà Nội: Khoa học xã hội.

- Hoang, Thi Quynh Hoa (1965), A phonological contrastive study of Vietnamese and English (PDF), Lubbock, Texas: Texas Technological College

- Kirby, James P. (2011), "Vietnamese (Hanoi Vietnamese)" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41 (3): 381–392, doi:10.1017/S0025100311000181

- Michaud, Alexis (2004), "Final consonants and glottalization: New perspectives from Hanoi Vietnamese", Phonetica, 61 (2–3): 119–146, doi:10.1159/000082560, PMID 15662108

- Michaud, Alexis; Vu-Ngoc, Tuan; Amelot, Angélique; Roubeau, Bernard (2006), "Nasal release, nasal finals and tonal contrasts in Hanoi Vietnamese: an aerodynamic experiment", Mon-Khmer Studies, 36: 121–137

- Nguyễn, Đăng-Liêm (1970), Vietnamese pronunciation, PALI language texts: Southeast Asia., Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-87022-462-X

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1955). Quốc-ngữ: The modern writing system in Vietnam. Washington, D. C.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1959). Hòa's Vietnamese-English dictionary. Saigon. (Revised as Nguyễn 1966 & 1995).

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1966). Vietnamese-English dictionary. Rutland, VT: C.E. Tuttle Co. (Revised version of Nguyễn 1959).

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1992). Vietnamese phonology and graphemic borrowings from Chinese: The Book of 3,000 Characters revisited. Mon-Khmer Studies, 20, 163–182.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1995). NTC's Vietnamese-English dictionary (rev. ed.). Lincolnwood, IL.: NTC Pub. Group. (Revised & expanded version of Nguyễn 1966).

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1996). Vietnamese. In P. T. Daniels, & W. Bright (Eds.), The world's writing systems, (pp. 691–699). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (1997), Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 1-55619-733-0

- Nguyễn, Văn Lợi; Edmondson, Jerold A (1998), "Tones and voice quality in modern northern Vietnamese: Instrumental case studies", Mon-Khmer Studies, 28: 1–18

- Phạm, Hoà. (2001). A phonetic study of Vietnamese tones: Reconsideration of the register flip-flop rule in reduplication. In C. Féry, A. D. Green, & R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Proceedings of HILP5 (pp. 140–158). Linguistics in Potsdam (No. 12). Potsdam: Universität Potsdam (5th conference of the Holland Institute of Linguistics-Phonology). ISBN 3-935024-27-4.

- Phạm, Hoà Andrea (2003), Vietnamese Tone – A New Analysis, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-96762-7

- Phạm, Hoà Andrea (2006), "Vietnamese Rhyme", Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 25: 107–142

- Thompson, Laurence (1959), "Saigon phonemics", Language, Language, Vol. 35, No. 3, 35 (3): 454–476, doi:10.2307/411232, JSTOR 411232

- Thompson, Laurence (1967), "The history of Vietnamese final palatals", Language, Language, Vol. 43, No. 1, 43 (1): 362–371, doi:10.2307/411402, JSTOR 411402

- Thompson, Laurence (1965), A Vietnamese reference grammar (1 ed.), Seattle: University of Washington Press., ISBN 0-8248-1117-8

- Thurgood, Graham. (2002). Vietnamese and tonogenesis: Revising the model and the analysis. Diachronica, 19 (2), 333–363.