Villa Romana del Casale

A mosaic from a bedroom in the villa | |

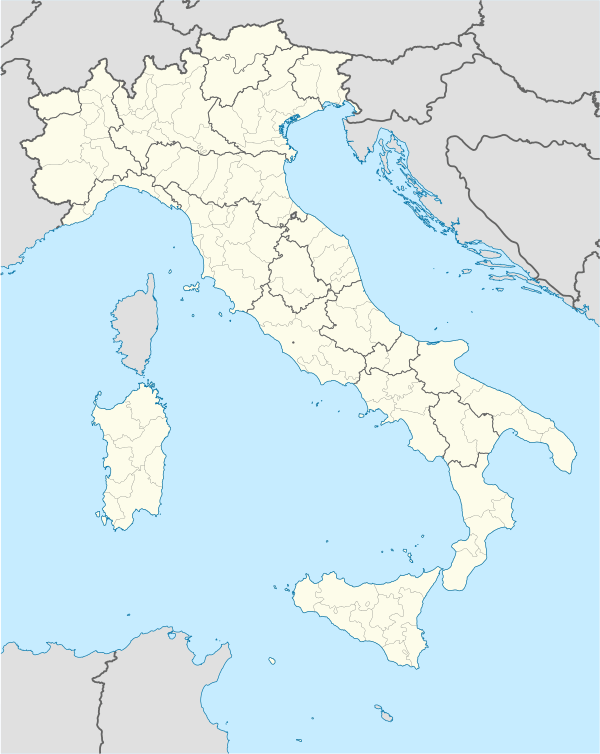

Shown within Italy | |

| Location | Piazza Armerina, Province of Enna, Sicily, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°21′53″N 14°20′05″E / 37.36472°N 14.33472°ECoordinates: 37°21′53″N 14°20′05″E / 37.36472°N 14.33472°E |

| Type | Roman villa |

| Area | 8.92 ha (22.0 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | First quarter of the 4th century AD |

| Abandoned | 12th century AD |

| Periods | Late Antiquity to High Middle Ages |

| Cultures | Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1929, 1935–1939, 1950–1960, 1970s |

| Archaeologists | Paolo Orsi, Giuseppe Cultrera, Gino Vinicio Gentili, Andrea Carandini |

| Condition | Preserved and excavated |

| Ownership | Public |

| Management | Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. di Enna |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website |

www |

| Official name | Villa Romana del Casale |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 832 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Villa Romana del Casale (Sicilian: Villa Rumana dû Casali) is a Roman villa urbana built in the first quarter of the 4th century and located about 3 km outside the town of Piazza Armerina, Sicily, southern Italy. It contains the richest, largest and most complex collection of Roman mosaics in the world,[1] and has been designated as one of 49 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Italy.[2]

History

The villa was constructed (on the remains of an older villa) in the first quarter of the 4th century AD, probably as the center of a huge latifundium (agricultural estate) covering the surrounding area. How long the villa had this role is not known, maybe for fewer than 150 years. The complex remained inhabited and a village grew around it, named Platia (derived from the word palatium (palace). The villa was damaged and perhaps destroyed during the domination of the Vandals and the Visigoths. The outbuildings remained in use, at least in part, during the Byzantine and Arab periods. The site was abandoned in the 12th century AD after a landslide covered the villa. Survivors moved to the current location of Piazza Armerina.

The villa was almost entirely forgotten, although some of the tallest parts of the remains were always above ground. The area was cultivated for crops. Early in the 19th century, pieces of mosaics and some columns were found. The first official archaeological excavations were carried out later in that century.

The first professional excavations were made by Paolo Orsi in 1929, followed by the work of Giuseppe Cultrera in 1935-39. The last major excavations took place in the period 1950-60. They were led by Gino Vinicio Gentili, after which a cover was built over the mosaics. In the 1970s Andrea Carandini carried out a few localized excavations at the site.

The latifundium and the villa

In late antiquity the Romans partitioned most of the Sicilian hinterland into huge agricultural estates called "latifundia" (sing. "latifundium"). The size of the villa and the amount and quality of its artwork indicate that it was the center of such a latifundium. The owner was probably a member of senatorial class if not of the imperial family itself, i.e., the absolute upper class of the Roman Empire.

The villa appeared to have served several purposes. It contained some rooms that were clearly residential, others that certainly had official purposes, and a number of rooms of as yet unknown intended use. They were definitely not built for commercial or production uses. The villa would likely have been the permanent or semi-permanent residence of the owner; it would have been where the owner, in his role as patron, received his local clients; and it would have functioned as the administrative center of the latifundium.

Only the manorial portions of the complex have yet been excavated. The ancillary structures: housing for slaves, workshops, stables, etc., have not been located.

The villa was a single-story building, centered on the peristyle, around which almost all the main public and private rooms were organized. Entrance to the peristyle is via the atrium from the west. Thermal baths are located to the northwest; service rooms and probably guest rooms to the north; private apartments and a huge basilica to the east; and rooms of unknown purpose to the south. Somewhat detached, and appearing almost as an afterthought, is the separate area to the south containing the elliptical peristyle, service rooms, and a huge triclinium (formal dining room).

The overall plan of the villa was dictated by several factors: older constructions on the site, the slight slope on which it was built, and the path of the sun and prevailing winds. The higher ground to the east is occupied by the Great Basilica, the private apartments, and the Corridor of the Great Hunt; the middle ground by the Peristyle, guest rooms, the entrance area, the Elliptical Peristyle, and the triclinium; while the lower ground to the west is dedicated to the thermal baths.

The whole complex is somewhat unusual, as it is organized along three major axes; the primary axis is the (slightly bent) line that passes from the atrium, tablinum, peristyle and the great basilica (coinciding with the path visitors would follow). The thermal baths and the elliptical peristyle with the triclinium are centered on separate axes. In spite of the different orientations of the various parts of the villa, they all form a single structure, built simultaneously. There is no indication that the villa was constructed in several stages.

Little is known about the earlier villa, but it appears to have been just a large country residence. It was probably built around the beginning of the second century.

Mosaics

Bikini girls

In 1959-60, Gentili excavated a mosaic on the floor of the room dubbed the "Chamber of the Ten Maidens" (Sala delle Dieci Ragazze in Italian). Informally called "the bikini girls", the maidens appear in a mosaic artwork which scholars named Coronation of the Winner. The young women perform sports including weight-lifting, discus throwing, running and ball-games. A girl in a toga offers a crown and victor's palm frond to "the winner".[3]

The Little Hunt

Another well-preserved mosaic shows a hunt, with hunters using dogs and capturing a variety of game.

Gallery

Closeup of the Bikini girls mosaic

Closeup of the Bikini girls mosaic The "skier" mosaic showing a youth in motion (not skiing as sometimes claimed)

The "skier" mosaic showing a youth in motion (not skiing as sometimes claimed)- A big cat attacks a hunter on the Great Hunt mosaic

- A ship on the Great Hunt mosaic

- A captured female tiger on the Great Hunt mosaic

- A hunter on the Great Hunt mosaic

- Hunters and a swastika on the Great Hunt mosaic

The Giant mosaic

The Giant mosaic Young boys hunting a rabbit, Child Hunter's Mosaic

Young boys hunting a rabbit, Child Hunter's Mosaic

References

- ↑ R. J. A. Wilson: Piazza Armerina. In: Akiyama, Terakazu (Ed.): The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 24: Pandolfini to Pitti. Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-517068-7.

- ↑ "World heritage site". Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ↑ Villa Romana del Casale, Val di Noto

Sources

- Petra C. Baum-vom Felde, Die geometrischen Mosaiken der Villa bei Piazza Armerina, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0940-2

- Brigit Carnabuci: Sizilien – Kunstreiseführer, DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1998, ISBN 3-7701-4385-X

- Luciano Catullo and Gail Mitchell, 2000. The Ancient Roman Villa of Casale at Piazza Armerina: Past and Present

- R. J. A. Wilson: Piazza Armerina, Granada Verlag: London 1983, ISBN 0-246-11396-0.

- A. Carandini - A. Ricci - M. de Vos, Filosofiana, The villa of Piazza Armerina. The image of a Roman aristocrat at the time of Constantine, Palermo: 1982.

- S. Settis, "Per l'interpretazione di Piazza Armerina", in Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Antiquité 87, 1975, 2, pp. 873–994.

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 105, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Villa Romana del Casale. |