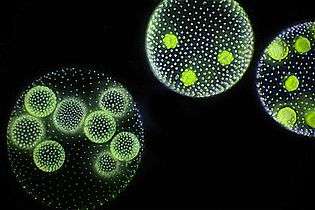

Volvox

| Volvox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Volvox sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Viridiplantae |

| Division: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Chlorophyceae |

| Order: | Volvocales |

| Family: | Volvocaceae |

| Genus: | Volvox L. |

| Species | |

|

Volvox aureus | |

Volvox is a polyphyletic genus of chlorophyte green algae in the family Volvocaceae. It forms spherical colonies of up to 50,000 cells. They live in a variety of freshwater habitats, and were first reported by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1700. Volvox diverged from unicellular ancestors approximately 200 million years ago.[1]

Description

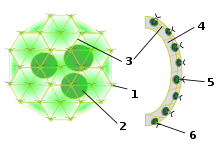

Volvox is a polyphyletic genus in the volvocine green algae clade.[2] Each mature Volvox colony is composed of up to thousands of cells from two differentiated cell types: numerous flagellate somatic cells and a smaller number of germ cells lacking in soma that are embedded in the surface of a hollow sphere or coenobium containing an extracellular matrix[1] made of glycoproteins.[3] Adult somatic cells comprise a single layer with the flagella facing outward. The cells swim in a coordinated fashion, with distinct anterior and posterior poles. The cells have anterior eyespots that enable the colony to swim towards light. The cells of colonies in the more basal Euvolvox clade are interconnected by thin strands of cytoplasm, called protoplasmates.[4] Cell number is specified during development and is dependent on the number of rounds of division. [2]

Reproduction

An asexual colony includes both somatic (vegetative) cells, which do not reproduce, and large, non-motile gonidia in the interior, which produce new colonies through repeated division. In sexual reproduction two types of gametes are produced. Volvox species can be monoecious or dioecious. Male colonies release numerous sperm packets, while in female colonies single cells enlarge to become oogametes, or eggs.[2][5]

Volvox is facultatively sexual and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. In the lab, asexual reproduction is most commonly observed; the relative frequencies of sexual and asexual reproduction in the wild is unknown. The switch from asexual to sexual reproduction can be triggered by environmental conditions[6] and by the production of a sex-inducing pheremone.[7] Dessication-resistant diploid zygotes are produced following successful fertilization.

Kirk and Kirk[8] showed that sex-inducing pheromone production can be triggered in somatic cells by a short heat shock given to asexually growing organisms. The induction of sex by heat shock is mediated by oxidative stress that likely also causes oxidative DNA damage.[6][9] It has been suggested that switching to the sexual pathway is the key to surviving environmental stresses that include heat and drought.[10] Consistent with this idea, the induction of sex involves a signal transduction pathway that is also induced in Volvox by wounding.[10]

Habitats

Volvox is a genus of freshwater algae found in ponds and ditches, even in shallow puddles.[5] According to Charles Joseph Chamberlain,[11]

"The most favorable place to look for it is in the deeper ponds, lagoons, and ditches which receive an abundance of rain water. It has been said that where you find Lemna, you are likely to find Volvox; and it is true that such water is favorable, but the shading is unfavorable. Look where you find Sphagnum, Vaucheria, Alisma, Equisetum fluviatile, Utricularia, Typha, and Chara. Dr. Nieuwland reports that Pandorina, Eudorina and Gonium are commonly found in summer as constituents of the green scum on wallows in fields where pigs are kept. The flagellate, Euglena, is often associated with these forms."

History

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first reported observations of Volvox in 1700.[12][13]

After some drawings of Henry Baker (1753),[14] Linnaeus (1758)[15] would describe the genus Volvox, with two species: V. globator and V. chaos. Volvox chaos is an amoeba now known as Chaos sp.[16][17]

Evolution

Ancestors of Volvox transitioned from single cells to form multicellular colonies at least 200 million years ago, during the Triassic period.[1][18] An estimate using DNA sequences from about 45 different species of volvocine green algae, including Volvox, suggests that the transition from single cells to undifferentiated multicellular colonies took about 35 million years.[1][18]

References

- 1 2 3 4 University of Arizona (February 22, 2009). "Single-celled algae took the leap to multicellularity 200 million years ago". Science Daily.

- 1 2 3 Kirk, David L. (1998). Volvox: A Search for the Molecular and Genetic Origins of Multicellularity and Cellular Differentiation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45207-6.

- ↑ Hallmann, A. (2003). "Extracellular matrix and sex-inducing pheromone in Volvox". International Review of Cytology. International Review of Cytology. 227: 131–182. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(03)01009-X. ISBN 978-0-12-364631-6.

- ↑ Ikushima, N.; Maruyama, S. (1968). "The protoplasmic connection in Volvox". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 15 (1): 136–140. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1968.tb02098.x.

- 1 2 Powers, J. H. (1908). "Further studies in Volvox, with descriptions of three new species". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 28: 141–175. doi:10.2307/3220908. JSTOR 3220908.

- 1 2 Nedelcu, AM; Michod, RE (2003). "Sex as a response to oxidative stress: the effect of antioxidants on sexual induction in a facultatively sexual lineage". Proc. Biol. Sci. 270 Suppl 2: S136–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0062. PMC 1809951

. PMID 14667362.

. PMID 14667362. - ↑ Hallmann, Armin (2003). "Extracellular Matrix and Sex-Inducing Pheromone in Volvox". International Review of Cytology. 227.

- ↑ DL, Kirk; Kirk, MM (1986). "Heat shock elicits production of sexual inducer in Volvox". Science. 231 (4733): 51–4. doi:10.1126/science.3941891. PMID 3941891.

- ↑ Nedelcu, AM; Marcu, O; Michod, RE (2004). "Sex as a response to oxidative stress: a twofold increase in cellular reactive oxygen species activates sex genes". Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 (1548): 1591–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2747. PMC 1691771

. PMID 15306305.

. PMID 15306305. - 1 2 Amon, P; Haas, E; Sumper, M (1998). "The sex-inducing pheromone and wounding trigger the same set of genes in the multicellular green alga Volvox". Plant Cell. 10 (5): 781–9. doi:10.2307/3870664. PMC 144025

. PMID 9596636.

. PMID 9596636. - ↑ Chamberlain, Charles Joseph (2007) [1932]. "Chlorophyceae". Methods in Plant Histology. Read Books. pp. 162–180. ISBN 978-1-4086-2795-2.

- ↑ van Leeuwenhoek, Antonie (1700). "Part of a Letter from Mr Antony van Leeuwenhoek, concerning the Worms in Sheeps Livers, Gnats, and Animalcula in the Excrements of Frogs" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 22 (260–276): 509–518. doi:10.1098/rstl.1700.0013.

- ↑ Herron, M. (2015). “…of the bignefs of a great corn of fand…”. Fierce Roller Blog, .

- ↑ Baker, H. (1753). Employment for the microscope. R. Dodsley: London, pl. XII, f. 27, .

- ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Editio decima revisa. Vol. 1 pp. [i-iv], [1]-823. Holmiae [Stockholm]: impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii.

- ↑ Herron, M. (2016). Moving without limbs! Linnaeus on Volvox. Fierce Roller Blog, .

- ↑ Spencer, M.A., Irvine, L.M. & Jarvis, C.E. (2009). Typification of Linnaean names relevant to algal nomenclature. Taxon 58: 237-260, .

- 1 2 Herron, MD; Hackett, JD; Aylward, FO; Michod, RE (2009). "Triassic origin and early radiation of multicellular volvocine algae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 106 (9): 3254–3258. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811205106.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volvox. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Volvox |

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. (2008). "Volvox". AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway.

- Volvox description with pictures from a Hosei University website

- YouTube videos of Volvox:

- Volvox, one of the 7 Wonders of the Micro World by Wim van Egmond, from Microscopy-UK

- Volvox carteri at MetaMicrobe.com, with modes of reproduction, brief facts