Zahir al-Umar

| Zahir al-Umar ظاهر العمر | |

|---|---|

Artistic representation of Zahir al-Umar by Ziad Daher Zedani, 1990 | |

| Governor of Sidon, Nablus, Jerusalem, Gaza, Ramla, Jaffa and Jabal Ajlun | |

|

In office 1774–1774 | |

| Preceded by | Darwish Pasha al-Kurji (Sidon) |

| Succeeded by | Jazzar Pasha (Sidon) |

| Sheikh of Acre and All Galilee Emir of Nazareth, Tiberias and Safad | |

|

In office 1768–1775 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Jazzar Pasha (Acre) |

| Multazim of Tiberias | |

|

In office 1730 – 1750s | |

| Preceded by | Umar al-Zaydani |

| Succeeded by | Salibi al-Zahir |

| Multazim of Deir Hanna | |

|

In office 1761–1767 | |

| Preceded by | Sa'd al-Umar |

| Succeeded by | Ali al-Zahir |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1689/1690 Arraba |

| Died |

21 August 1775 Acre |

| Relations | Zaydani family |

| Children | Salibi, Ali, Uthman, Sa'id, Ahmad, Salih, Sa'd al-Din, Abbas (surnames: al-Zahir) |

| Parents | Umar al-Zaydani |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

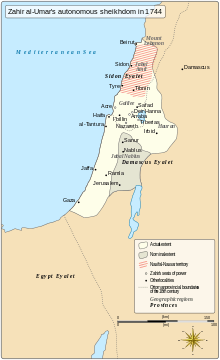

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani (alternatively spelled Dhaher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar) (Arabic: ظاهر آل عمر الزيداني; Ẓāhir āl-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 August 1775) was the virtually autonomous Arab ruler of northern Palestine in the mid-18th century,[1] while the area was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire. For much of his reign, starting in the 1730s, his domain mainly consisted of Galilee, with successive headquarters in Tiberias, Arraba, Nazareth, Deir Hanna and finally Acre, in 1746. He fortified Acre, and the city became a center of the cotton trade between Palestine and Europe. In the mid-1760s, he reestablished the port town of Haifa nearby.

Zahir successfully withstood assaults and sieges by the Ottoman governors of the Sidon and Damascus provinces, who attempted to limit or eliminate his influence. He was often supported in these confrontations by the rural Shia Muslim clans of Jabal Amil. In 1771, in alliance with Ali Bey al-Kabir of Egypt Eyalet and with backing from the Russian Empire, Zahir captured Sidon, while Ali Bey's forces conquered Damascus, both acts in open defiance of the Ottoman sultan. At the peak of his power in 1774, Zahir's autonomous sheikhdom extended from Beirut to Gaza and included the Jabal Amil and Jabal Ajlun regions. By then, however, Ali Bey had been killed, the Ottomans entered into a truce with the Russians, and the Sublime Porte felt secure enough to check Zahir's power. The Ottoman Navy attacked his Acre stronghold in the summer of 1775 and he was killed outside of its walls shortly after.

The wealth Zahir accumulated through monopolizing Palestine's cotton and olive oil trade to Europe financed his sheikhdom. For much of his rule, he oversaw a relatively efficient administration and maintained domestic security, although he faced and suppressed several rebellions by his sons. The aforementioned factors, along with Zahir's flexible taxation policies and his battlefield reputation made him popular among the local peasantry. Zahir's tolerance of religious minorities encouraged Christian and Jewish immigration to his domain. The influx of immigrants from other parts of the empire stimulated the local economy and led to the significant growth of the Christian communities in Acre and Nazareth and the Jewish community in Tiberias. He and his family, the Zaydani clan, also patronized the construction of commercial buildings, houses of worship and fortifications throughout Galilee. Zahir's founding of a virtually autonomous state in Palestine has made him a national hero among Palestinians today.[2]

Early life

Zahir was born in the village of 'Arrabat al-Battuf in central Galilee.[3][4] His date of birth is not definitively known, with the years 1686, 1689/90 and 1694 cited by Zahir's contemporary biographers Volney, Mikha'il Sabbagh and Khalil al-Muradi, respectively. According to biographer Ahmad Hasan Joudah, 1689/1690 is the most likely year of his birth because he considers Sabbagh to be the most reliable source for Zahir's personal life.[5] The proper transliteration of his given name is Ẓāhir, but in the local dialect of Arabic used in Galilee, his name was pronounced Ḍāhir.[5] Zahir's family, the Zaydani clan, were Sunni Muslim[6] notables from the Qaisi tribal confederation based in the Tiberias area who had strong connections to the Arab-Bedouin tribesmen of Galilee, which at the time was part of the Ottoman Empire. Zahir was the youngest of four sons born to Sheikh Umar al-Zaydani;[3] his brothers were Sa'd, Salih "Abu Dani" and Yusuf, and his sister was Shammah.[7] Zahir grew up in the village of Saffuriya.[3]

Zahir's father and grandfather had both served as the multazim (chief tax collector) of Tiberias, having been appointed by the Druze emirs (princes) of the Ma'an dynasty which governed the region from their headquarters in Mount Lebanon.[8] In 1698, Umar az-Zaydani was appointed multazim of the Safad region by Bashir Shihab I, the Sunni Qaisi emir who succeeded the Ma'ans as governor of the Mount Lebanon Emirate.[9] The Zaydani family maintained commercial trade relations extending from Galilee to Aleppo and controlled tax farms in Galilee; Zahir's uncle Ali, for instance, held the tax farm of al-Damun. Zahir's elder brother Sa'd became the head of the family when their father died in 1706, but the family's tax farms were transferred to Zahir, who was still a teenager. This was done as a precautionary measure, so that in the event of a default in tax payments, the Ottoman government would not be able to hold the practical owners of the tax farms accountable. Nonetheless, legal ownership of the Zaydani tax farms gave Zahir considerable power within his clan.[8]

In 1707, Zahir was involved in a brawl in Tiberias in which he killed a man. As a result, Sa'd opted to move the family to Arraba after being offered safe haven there by the Bani Saqr tribe. In Arraba, Zahir received a degree of formal education from a certain Muslim scholar, Abd al-Qadir al-Hifnawi. During his youth, Zahir also learned how to hunt and fight. When the village of Bi'ina was attacked by forces dispatched by the governor of Sidon Eyalet sometime between 1713 and 1718, Zahir played an important role in defending the village and managed to evade the governor's troops. According to chroniclers of the time, this event, along with Zahir's moderation, turned Zahir into a folk hero in the area. His martial talents gained him further respect among the local peasantry throughout the 1720s.

Along with Sa'd, he also gained prestige among the people of Damascus, with whom he continued the commercial relationships established by his father.[8] Among the contacts Zahir made there was the Muslim scholar Abd al-Ghaffar al-Shuwaki, who introduced Zahir to Sayyid Muhammad of the al-Husayni family, which provided the sharifs of Damascus at the time;[8] Zahir married Sayyid Muhammad's daughter and moved to Nazareth because she considered Arraba too small. When Sayyid Muhammad died, Zahir inherited his fortune.[10]

Rule

Consolidation of power in Galilee

In the late 1720s, Zahir and his brother Yusuf, backed by the Bani Saqr, captured Tiberias and its multazim. Concurrently, Zahir issued a letter to Köprülü Abdullah Pasha, governor of Sidon Eyalet, accusing the multazim of oppression and of imposing illegal taxes on the population. Zahir insisted that if Abdullah Pasha appointed him multazim of Tiberias and Arraba, he would guarantee the timely payment of taxes and rule justly. Abdullah Pasha consented to Zahir's rule and sent him an honorary robe.[11] This was the first time a Zaydani multazim was directly appointed by the governor of Sidon rather than the semi-autonomous rural chiefs of Mount Lebanon.[12] Zahir made Tiberias his principle base and was joined by his Zaydani kinsmen. He appointed his cousin Muhammad ibn Ali, the multazim of al-Damun, as commander of the family militia.[13]

Zahir extended his rule southward toward Nazareth and the Marj Ibn Amer plain (Jezreel Valley) between Galilee and Jabal Nablus.[3] Capturing these areas was a drawn-out process, and Zahir's efforts to take Nazareth (a town in Safad Sanjak, but controlled by the Jarrar clan based in Nablus Sanjak) caused the ruling clans of the Nablus hinterland (Jabal Nablus), along with Zahir's erstwhile allies in the Bani Saqr tribe, to challenge him. Zahir, meanwhile, relied on his Zaydani kinsmen, Maghrebi mercenaries whom he commissioned in the mid-1730s under commander Ahmad Agha al-Dinkizli, and Nazareth's residents.[13] In 1735, Zahir's 2,000-strong force routed the Jarrars and the Bani Saqr at al-Rawha in Marj Ibn Amer,[14] killed their leader Sheikh Ibrahim al-Jarrar, and captured Nazareth.[15] According to historian Hanna Samarah, Zahir's forces inflicted 8,000 fatalities among the Jarrar-Saqr coalition during the battle.[16]

Following his victory at Marj Ibn Amer, 4,000 locals, including many residents of Nazareth,[14] joined Zahir's forces to completely subdue Jabal Nablus. Among Zahir's supporters were Christian women from Nazareth who supplied his troops with food and water.[16] Zahir's forces pursued the Jarrars to their throne village of Sanur, but ultimately withdrew after failing to subdue the fortress. This defeat marked the limit of Zahir's influence south of Marj Ibn Amer and established the Jarrars as the dominant force of Jabal Nablus over their rivals, the Tuqans.[13] While the Jarrars and Zahir eventually concluded a truce, the former continued to mobilize the clans of Jabal Nablus to prevent Zahir's southward expansion.[17]

In 1738, Zahir's forces captured the fortress at Jiddin and the villages in its political orbit, Abu Snan and Tarshiha.[12] Jiddin had been ruled by Ahmad al-Husayn, whose family historically controlled it. The peasants under his rule complained that he governed oppressively and appealed to Zahir, who was known for treating the peasantry fairly, to relieve them of al-Husayn. Zahir, eager to expand his control toward the Mediterranean, accepted their requests and obtained permission from the governor of Sidon, Ibrahim Pasha al-Azm, to seize the fortress. Likewise, al-Husayn had also approached the governor, who, hoping to see two powerful local leaders weakened, gave al-Husayn his blessing as well. Zahir assembled a 1,500-strong force and defeated al-Husayn's forces near the fortress. He was then appointed multazim of Jiddin's subdistrict.[18]

Bi'ina, which was also fortified, withstood a siege by Zahir in 1739, but Zahir later married the daughter of Bi'ina's mukhtar (headman), and thus brought Bi'ina into his domain.[13] He also acquired the fortress of Suhmata through diplomatic means,[19] further solidifying his rule over northern and eastern Galilee. In 1740, Zahir made an agreement with the neighboring Bedouin tribes to end their looting raids in the area. By then, Sa'd had taken control of Deir Hanna and Muhammad ibn Ali captured Shefa-'Amr, entrenching the presence of the Zaydani clan in western Galilee.[13] After negotiations, Muhammad al-Naf'i, the multazim of Safad, surrendered the city to Zahir.[12] Safad was the administrative seat of the sanjak and situated on a strategic hill overlooking the Galilee countryside.[20] Zahir later acquired the fortified village of Deir al-Qassi after marrying the daughter of its sheikh, Abd al-Khaliq Salih.[19]

Zahir's conquest of the Safad region and western Galilee removed the barriers between him and the Metawali (Shia Muslim) clans of Jabal Amil. Zahir informed the Metawalis' sheikh, Nasif al-Nassar, of his intent to acquire the fortified villages of al-Bassa and Yaroun on the borders between the Zaydani and Metawali sheikhdoms. In response, Sheikh Nasif launched an assault against Zahir and the two sides confronted each other in indecisive skirmishes in the border village of Tarbikha. Zahir then received reinforcements from his Maghrebi cavalry and defeated the Metawalis, pursuing Sheikh Nasif to his headquarters in Tibnin. Zahir's brother Sa'd mediated an end to the fighting and secured a mutual defense pact between Zahir and Sheikh Nasif, whereby the former would receive control of al-Bassa and Yaroun and the Metawalis' support in his confrontations with the governors of Damascus; in return, Sheikh Nasif's sons, who were captured by Zahir's troops, were released, the Metawalis' tax payments to Sidon were reduced by some 25 percent, and Zahir guaranteed his backing of Sheikh Nasif in any confrontation with the governors of Sidon.[21]

Zahir, similar to other local strongmen in the Ottoman Empire who did not owe their power to the central Ottoman authorities, was disliked by the Ottoman administration. The Ottoman Sultan sent an order to the governor of Damascus Eyalet, Sulayman Pasha al-Azm, to put an end to Zahir's rule in Galilee. In September 1742, a military force led by the governor of Damascus came to Galilee and laid siege to Tiberias. After 83 days, the siege was lifted due to the departure of the Hajj pilgrim caravan.[22] Using this respite, Zahir reinforced the defenses of Tiberias and Shefa-'Amr. In July 1743, backed by the Bani Saqr, the wali of Tripoli and the district governors of Jerusalem, Gaza and Irbid, Sulayman Pasha renewed his expedition, this time seeking to reduce Deir Hanna and sever Tiberias's links to the outside. Sulayman died suddenly in Lubya and Zahir used the opportunity to assault Sulayman's troops, capturing their camp.[23] In 1745, Zahir had a fortress erected on a hill overlooking Saffuriya.[24]

Ruler of Acre

.jpg)

Zahir consolidated his authority over Acre in a drawn-out process starting in the 1730s. His Acre-based partner, the Melkite merchant Yusuf al-Qassis, served as an early link between Zahir and the French merchants of Acre.[25] Zahir's first contact with the merchants came in 1731 when he arranged the settlement of debts owed to them by his brother Sa'd.[26] In 1743,[27] To stymie his cousin Muhammad ibn Ali's ambitions in Acre, Zahir had him arrested and executed.[25] In 1743, Zahir requested the tax farm of Acre from the governor of Sidon, Ibrahim Pasha al-Azm, who, wary of Zahir's growing power in the province, rejected the request. Instead, Zahir took Acre by force in July 1746.[28]

In the first few years following his takeover of Acre, Zahir resided in the fortress of Deir Hanna in the heart of Galilee. He began fortifying Acre by building walls around the city in 1750. He built other fortifications and buildings in Acre as well.[28] In 1757 he took control of the Mediterranean port villages of Haifa and Tantura, and nearby Mount Carmel, all of which had been part of Damascus Eyalet, unlike most of Zahir's domain at the time, which was in Sidon Eyalet.[28][29] He also captured the port village of al-Tira, between Tantura and Haifa, at that time. Zahir's stated justification to the Ottoman authorities for conquering Palestine's northern coastal plain was to protect the area from Maltese pirates.[30]

In late 1757, the Bani Saqr and Sardiyah tribes, who Zahir maintained ties with,[31] launched an assault on the Hajj caravan as it was returning to Syria from Mecca. Thousands of Muslim pilgrims were killed in the raid, including Sultan Osman III's sister. The attack shocked the Sublime Porte (Ottoman imperial government),[32] and discredited the governor of Damascus and amir al-hajj, Husayn Pasha ibn Makki, for failing to ward off the Bedouin. Husayn Pasha had been serving his first term as governor, having replaced As'ad Pasha al-Azm, who Zahir had peaceful relations with, and among Husayn Pasha's priorities were subduing Zahir and annexing his territories, which were part of Sidon Eyalet. Husayn Pasha lodged a complaint to the Sublime Porte alleging Zahir's involvement in the raid. Zahir denied the allegation and pressed for an investigation into the assault. He also sought to earn the Sublime Porte's favor by purchasing the looted goods of the caravan from the tribes, including the decorated banners representing Muhammad and the sovereignty of the sultan, and restoring them to Sultan Mustafa III (Osman III had died on 30 October). Moreover, Zahir's enemy Husayn Pasha was dismissed that year.[31]

Husayn Pasha's replacement, Uthman Pasha al-Kurji,[33] who took office in 1760,[34] sought to retrieve control of Haifa from Zahir.[33] Uthman Pasha requested that the governor of Sidon, Nu'man Pasha, recapture the port city on his behalf, to which Nu'man Pasha complied, dispatching 30 Maghrebi soldiers on a vessel captained by a Frenchman on 20 May 1761.[35] The effort was a meager attempt and upon arrival, Zahir had the ship confiscated and its soldiers arrested, while the French captain paid a fine. The issue over Haifa's annexation was smoothed over with the assistance of an Istanbul-based Ottoman official and friend of Zahir, Yaqub Agha. Yaqub had a high-ranking official named Sulayman Agha intervene in the matter and revoke Uthman Pasha's orders.[33]

Intra-family conflict

In 1761, Zahir ordered his son Uthman al-Zahir to assassinate Zahir's brother Sa'd because the latter had been collaborating with Uthman Pasha and the Bani Saqr tribe to kill Zahir and replace him.[27][36] Sa'd's assassination indirectly led to the first conflict between Zahir and his sons, in this case Uthman. The latter had been promised control over Shefa-'Amr in return for killing Sa'd, but Zahir reneged due to pleas by Shefa-'Amr's residents not to appoint Uthman as their governor. Backed by his full-brothers Ahmad and Sa'd al-Din, who were angered by Zahir's refusal to cede them more territory, Uthman besieged Shefa-'Amr in 1765. However, under Zahir's instructions, the locals in the vicinity defended the town and succeeded in preventing its capture. The three brothers then appealed to Zahir's eldest and most loyal son, Salibi, to intervene on their behalf with Zahir, but Salibi was unable to persuade Zahir to make concessions. The four brothers then attempted to rekindle their alliance with the Bani Saqr, who Zahir had since routed at the Marj Ibn Amer plain in 1762.[36]

The brothers' efforts to recruit the Bani Saqr failed when Zahir bribed the tribe not to back his sons and subsequently had Uthman imprisoned in Haifa for six months before exiling him to a village near Safad.[37] Meanwhile, in 1765, Zahir had Haifa demolished and then rebuilt and fortified at a site three kilometers to the southeast in 1769. While the old village was situated on a plain, the new town, which remained a port along the Haifa Bay, was built on a narrow strip of land at the northern foot of Mount Carmel to make it easier to defend by land.[38] In May 1766, Uthman renewed his rebellion against Zahir with backing from the Druze clans of Galilee, but this coalition was defeated by Zahir near Safad. This conflict expanded to include competing Druze and Shia factions from Mount Lebanon and Jabal Amil, with Emir Mansur Shihab (the Sunni leader of a Druze faction) and the Metawali, Sheikh Qublan, siding with Zahir, while Emir Yusuf Shihab (the leader of another Druze faction) and Sheikh Nasif sided with Uthman.[37] Mediation by Emir Isma'il Shihab of Hasbaya culminated in a successful peace summit near Tyre between the two factions and a reconciliation between Zahir and Uthman, whereby the latter was granted control of Nazareth.[39]

In September 1767, conflict between Zahir and his son Ali al-Zahir of Safad commenced over the former's refusal to cede to the latter control of the strategic fortress of Deir Hanna or the village of Deir al-Qassi. Prior to the dispute, Ali had been loyal to Zahir and proven himself effective in helping his father suppress dissent among his brothers and in battles against external enemies. Zahir's forces intimidated Ali into surrendering later that month, and Zahir pardoned and ultimately ceded to him Deir al-Qassi. However, conflict was renewed weeks later with Ali and his brother Sa'id, backed by Sheikh Nasif, Emir Yusuf and Uthman Pasha poised against Zahir, Uthman, Sheikh Qublan and Muhammad Pasha al-Azm, governor of Sidon. With mediation from Ibrahim Sabbagh, Zahir's financial adviser, Zahir settled his dispute with Sa'id, granting the latter control over Tur'an and Hittin.[40]

Ali refused to negotiate, gained the backing of Salibi, and the two defeated their father, who had since demobilized his troops and was relying on local civilian volunteers from Acre.[40] When Zahir re-mobilized his Maghrebi mercenaries in Acre he launched an offensive and defeated Ali, who subsequently fled Deir Hanna in October. Out of sympathy for Ali's children, who remained in the fortress village, he pardoned Ali on the condition he pay 12,500 piasters and 25 Arabian horses for the fortress.[27] By December 1767, Zahir's intra-family disputes were put to rest for several years (until 1774–75), and through the intercession of Uthman, a close and enduring alliance was established between Zahir and Sheikh Nasif.[41]

In 1768 the central Ottoman authorities partially recognized or legitimized Zahir's de facto political position by granting him the title of "Sheikh of Acre, Emir of Nazareth, Tiberias, Safed, and Sheikh of all Galilee".[1] However, this official recognition was tempered when Yaqub Agha was executed shortly after and Sulayman Agha died in 1770, depriving Zahir of close allies in Istanbul. In November 1770, Uthman Pasha had the governor of Sidon replaced by his son Darwish Pasha and had his other son, Muhammad Pasha, appointed governor of Tripoli Eyalet. Uthman Pasha was committed to ending Zahir's rule, and Zahir's position was left particularly vulnerable with the loss of support in Istanbul.[42] In response to threats from Damascus, Zahir further strengthened Acre's fortifications and armed every adult male in the city with a rifle, two pistols and a sabre. He also moved to mend ties with his sons, who held various tax farms in Galilee, and consolidate his relationship with the Shia clans of Jabal Amil, thereby strengthening his local alliances.[43]

Alliance with Ali Bey and war with Damascus

Although Zahir was bereft of friends in Istanbul and Damascus, he was forging a new alliance with the increasingly autonomous Mamluk ruler of Egypt and the Hejaz, Ali Bey al-Kabir. Ali Bey shared a common interest with Zahir to subdue Damascus as he sought to extend his influence to Syria for strategic purposes vis-a-vis his conflict with the Sublime Porte. He had dispatched 15,000-20,000 Egyptian troops to the port cities of Gaza and Jaffa under commander Ismail Bey.[44] Together, Zahir and Ismail crossed the Jordan Valley with their armies and moved north toward Damascus. They made it as far as Muzayrib, but Ismail abruptly halted his army's advance after confronting Uthman Pasha as he was leading the Hajj caravan in order to avoid harming the Muslim pilgrims. Ismail considered attacking the governor at that point to be a grave religious offense. He subsequently withdrew to Jaffa.[45]

Zahir was surprised and angered by Ismail's reticence to attack. In a unilateral move to impose his authority in Uthman Pasha's jurisdiction, Zahir had his son Ahmad and other subordinate commanders collect taxes from villages in Damascus Eyalet, including Quneitra, while he dispatched his other son Ali on a campaign against the Bani Nu'aym tribe in Hauran, also part of Damascus.[46] In response to Zahir's indignation, Ali Bey sent him 35,000 troops under Abu al-Dhahab in May.[44] Together with Ismail's troops in Jaffa,[45] the Egyptian army captured Damascus from Uthman Pasha in June, while Zahir and his Metawali allies captured the city of Sidon from Darwish Pasha. However, Abu al-Dhahab was persuaded by Ismail that confronting the Ottoman sultan, who carried a high religious authority as the caliph of Islam, was "truly ... a scheme of the Devil" and a crime against their religion.[47] A short time after capturing Damascus, Abu al-Dhahab and Ismail subsequently withdrew from the city, whose inhabitants were "completely astonished at this amazing event", according to a chronicler of the time period.[47] The sudden turn of events compelled Zahir's forces to withdraw from Sidon on 20 June.[48]

Abu al-Dhahab's withdrawal frustrated Zahir who proceeded to make independent moves, first by capturing Jaffa in August 1771,[44] after driving out its governor Ahmad Bey Tuqan, and shortly thereafter, capturing the cotton-producing Bani Sa'b region (centered around modern-day Tulkarm), which was held by Mustafa Bey Tuqan.[49] Zahir had Jaffa fortified and stationed 2,000 troops there.[44] By the end of August, Zahir remained in control of Jaffa, while Uthman Pasha had restored his control over Ramla and Gaza.[50]

Peak of power

In an attempt to expand his zone of influence to Nablus, the commercial center of Palestine and its agriculturally-rich hinterland, Zahir besieged Nablus in late 1771. By then, Zahir had secured an alliance with the powerful Jarrar clan,[51] who were incensed at Uthman Pasha's assignment of Mustafa Bey Tuqan as the collector of the miri (hajj pilgrimage tax).[52] Nablus was under the de facto control of the Tuqan and Nimr clans, local rivals of the Jarrars. The loss of Jaffa and Bani Sa'b stripped Nablus of its sea access. Nablus was defended by 12,000 mostly peasant riflemen under Nimr and Tuqan commanders. After nine days of clashes, Zahir decided to withdraw and avoid a costly stalemate. As he departed Nablus, his forces raided many of the city's satellite villages, from which its peasant defenders originated.[51]

Uthman Pasha had resumed his governorship of Damascus at the end of June 1771 and was determined to eliminate Zahir. To that end, he assembled a coalition that included his sons Darwish Pasha al-Kurji and Muhammad Pasha al-Kurji, who were the governors of Sidon and Tripoli, respectively, and Emir Yusuf Shihab of Mount Lebanon. In late August Uthman Pasha reached Lake Hula at the head of 10,000 Ottoman troops.[50] Before Uthman Pasha could be joined by his allies, Zahir and Sheikh Nasif of the Metawalis confronted the governor's troops on 2 September. Ali al-Zahir, Zahir's son and a commander of one of his four battlefield regiments, raided Uthman Pasha's camp, while Zahir's other troops blocked them from the west. Uthman Pasha's troops hastily retreated towards the Jordan River, the only place where they were not surrounded. The overwhelming majority drowned in the river, with only 300–500 survivors, including Uthman Pasha who almost drowned but was rescued by one of his men.[53] The Battle of Lake Hula marked a decisive victory for Zahir, who entered Acre triumphantly with the spoils of Uthman Pasha's camp. He was celebrated by the residents of the city and on the way there, he was given honorary gun salutes by each of his fortified villages on the route between Tiberias and Acre. He also received congratulations from the French merchant ships at the port of Acre. Zahir's victory encouraged Ali Bey to relaunch his Syrian campaign.[53]

Following his victory against Uthman Pasha, Zahir demanded Darwish Pasha vacate Sidon, which he did on 13 October. He returned two days later after receiving the backing of Emir Yusuf. Zahir decided to move against Emir Yusuf, and together with his ally Sheikh Nasif, he confronted him at Nabatieh on 20 October. Emir Yusuf's men numbered some 37,000. Zahir's Metawali cavalry engaged in a maneuver where they fled the battlefield in apparent defeat, only to have the pursuant troops of Emir Yusuf surrounded by Zahir's men, who dealt Emir Yusuf's army a decisive blow. Emir Yusuf thereafter retreated to his mountain village of Deir al-Qamar, while Sidon was left under the protection of Ali Jumblatt and 3,000 Druze defenders. However, with news of Zahir's victory, Ali Jumblatt and Darwish Pasha withdrew from Sidon, which was subsequently occupied by Zahir and Sheikh Nasif. Uthman Pasha and all of his sons were consequently dismissed from their posts by the Sublime Porte.[54] Although, he could not capture Nablus and its hinterland, Zahir's domain by the end of 1771 extended from Sidon to Jaffa and included an influential presence in the Hauran plain.[55]

Muhammad Tuqan captured Jaffa from Zahir in May 1772, the same month that Ali Bey arrived in Acre to seek Zahir's protection after being forced out of Egypt by rival mamluks. In June, the Ottoman loyalist Jazzar Pasha sought to establish himself in Lebanon and took over Beirut from the local Druze chieftains. The Druze had previously been in conflict with Zahir, but due to Jazzar's offensive, the circumstances fostered an alliance between them, Zahir and the Metawali clans of Jabal Amil. Zahir and Ali Bey sought to take back Jaffa and, with help from the Russian Fleet, succeeded after a nine-month siege, in which they exhausted many of their resources. Prior to that, in late October 1772, Zahir and his Lebanese allies captured Beirut from Jazzar, also with Russian naval support.[55]

In March 1773, Ali Bey left Palestine to reestablish himself in Egypt, but Abu al-Dhahab had him killed when he arrived there.[55] With this came an end to the alliance between Zahir and Ali Bey, which had brought together Egypt and Palestine politically and economically in a way that had not occurred since the early 16th century.[56] While their attempts to unite their territories economically and politically were unsuccessful, their rule posed the most serious domestic challenge to Ottoman rule in the 18th century.[57] As a consequence of Ali Bey's death, Zahir moved to further strengthen his hold over Jaffa and capture Jerusalem, but he failed in the latter attempt. All of Ottoman Syria came under the official command of Uthman Pasha al-Misri in 1774 in order to bring stability to the provinces of the region. Al-Misri did not seek conflict with Zahir and sought to establish friendly terms with him. As such, he convinced the Sublime Porte to officially appoint Zahir as the governor of Sidon as long as Zahir paid all of the taxes the province had owed to the Porte. Al-Misri further promoted Zahir in February by declaring him "Governor of Sidon, Nablus, Gaza, Ramla, Jaffa and Jabal Ajlun", although this title was not officially sanctioned by the Porte.[55] In effect, Zahir was the de facto ruler over Palestine (with the exception of Nablus and Jerusalem), Jabal Amil, and the Syrian coast from Gaza to Beirut.[58]

Downfall

Al-Misri was recalled to Istanbul in the summer of 1774 and Muhammad Pasha al-Azm was appointed governor of Damascus. Thus, Zahir's governorship of Sidon was left vulnerable because it had largely depended on guarantees from al-Misri. Al-Azm sought peaceful relations with Zahir, but the Sublime Porte, having made peace with Russia and relieving itself from that conflict, aimed to undermine the rebellious rulers of its provinces, including Zahir. Al-Azm managed to secure an official pardon of Zahir from the Porte in April 1775, but not the governorship of Sidon. Meanwhile, conflict between Zahir and his sons had reignited, with Ali of Safad attempting to capture Zahir's villages in Galilee in 1774. Zahir defeated Ali with support from his other son, Ahmad of Tiberias. Afterward, Zahir's rule was again challenged by one of his other sons, Sa'id,[59] later that year. In response to this challenge, Zahir armed and mobilized 300 of Acre's civilian inhabitants to counter Sa'id.[60] Ali continued to undermine Zahir's rule by encouraging defections by Zahir's Maghrebi mercenaries through bribes.[59]

On 20 May 1775, Abu al-Dhahab, having been encouraged by the Porte to eradicate Zahir's influence, captured Jaffa and slaughtered its male inhabitants. News of the massacre spurred the people of Acre into a mass panic, with its residents fleeing and storing their goods in the city's Khan al-Ifranj (the French Caravanserai) for safekeeping. On 24 May, Zahir also departed the city, leaving for Sidon.[61] Ali al-Zahir, subsequently entered it and declared himself governor. However, Ali's Maghrebi troops abandoned him and looted the city as Abu al-Dhahab's troops approached it a few days later.[59] They proceeded to conquer Sidon by sea, prompting Zahir to seek shelter with Shia allies in Jabal Amil.[61] Some of Zahir's sons attempted to secure their own peace with Abu al-Dhahab, but the latter became ill and died on 10 June, causing the collapse and chaotic withdrawal of his Egyptian troops from Acre. Zahir re-entered the city two days later and reestablished order with the assistance of Ahmad Agha al-Dinkizli.[62] However, the setback of Abu al-Dhahab's death did not preclude the Sublime Porte from attempting to check Zahir's power and Sidon remained in Ottoman hands.[63]

On 23 April, the Porte dispatched the Ottoman Navy admiral, Hasan Pasha al-Jazayiri, to blockade Acre. He reached Haifa on 7 August taking Jaffa from Zahir's son-in-law, Karim al-Ayyubi.[63] Hasan Pasha ordered Zahir to pay the miri dues he owed to the Sublime Porte dating back to 1768. Zahir initially agreed to pay 500,000 piasters of the total amount upfront and a further 50,000 piasters to Hasan Pasha himself to "spare the blood of the people".[63] Hasan Pasha apparently accepted Zahir's proposals, but the arrangements fell apart.[63]

The accounts differ as to exactly how the negotiations collapsed, but sources agree that their failure was the result of disputes within Zahir's inner circle between his financial adviser Ibrahim Sabbagh and his chief military commander, al-Dinkizli.[63] Most accounts claim that Sabbagh urged Zahir not to pay Hasan's requested sums and agitated for war. Sabbagh argued that Zahir's treasury did not have the funds to pay the miri dues and that Zahir's forces were capable of defeating Hasan. Al-Dinkizli pressed Zahir to pay the amount, arguing that mass bloodshed could be averted. He advised Zahir to force Sabbagh to pay the amount if Zahir could not afford to himself. When the negotiations dragged on, Hasan pressed for a full repayment of the miri dues, warning Zahir that he would be executed if he failed to satisfy the demand. Zahir was insulted by Hasan's threat and in turn threatened to destroy Hasan's entire fleet unless he withdrew his ships.[64]

Hasan proceeded to bombard Acre, and Zahir's Maghrebi artillerymen responded with cannon fire, damaging two of Hasan's ships. The following day, Hasan's fleet fired roughly 7,000 shells against Acre without returning fire from the city's artillerymen;[64] al-Dinkizli had called on his Maghrebi forces to refrain from returning fire because as Muslims they were forbidden from attacking the sultan's military. Realizing his long-time deputy commander's betrayal, he attempted to flee Acre on 21 August or 22 August. As he departed its gates, he was fired on by Ottoman troops, with a bullet striking his neck and causing him to fall off his horse. A Maghrebi soldier then decapitated him. Zahir's severed head was subsequently delivered to Istanbul.[65]

Aftermath

Following his death, Sabbagh and Zahir's sons Abbas and Salih were arrested by Hasan Pasha's men.[66] The Sublime Porte also seized property belonging to Zahir, his sons and Sabbagh, which valued at 41,500,000 piasters. They were imprisoned in Istanbul, the Ottoman capital along with their physician, who was known to be talented in his profession. The physician was summoned by the sultan to treat his wife's ailment, which he did successfully, earning him his freedom from incarceration and a medal of honor from the sultan. The physician used his influence with the authorities to have Zahir's children and grandchildren released and returned to their hometowns. Sabbagh was executed by Hasan Pasha.[67] Al-Dinkizli was rewarded with the governorship of Gaza, but died on the way to his new headquarters, likely having been poisoned by Hasan.[65]

Zahir's sons Uthman, Ahmad, Sa'id and Ali continued to put up resistance, with the latter putting up the longest fight from his fortress in Deir Hanna. The fortress eventually capitulated to the combined forces of Hasan Pasha and Jazzar Pasha on 22 July 1776. Ali fled, but was killed later that year in the area between Tiberias and Safad. By then, the rest of Zahir's sons had been arrested or killed. Abbas was later appointed by Sultan Selim III as the Sheikh of Safad. However, in 1799, when Napoleon invaded Palestine, but withdrew after being defeated in Acre, Abbas and Salih both left Safad with the departing French forces. This marked the end of Zaydani influence in Galilee.[66]

Constantin-François Volney, who wrote the first European biography of Zahir in 1787,[68] lists three main reasons for Zahir's failure. First, the lack of "internal good order and justness of principle". Secondly, the early concessions he made to his children. Third, and most of all, the avarice of his adviser and confidant, Ibrahim Sabbagh.[69]

Politics

Administration

Zahir appointed many of his brothers and sons as local administrators, particularly after he consolidated his control over Acre,[70] which became the capital of his territory. Except for Acre and Haifa, Zahir divided the remainder of his territory between his relatives. His eldest brother was appointed to Deir Hanna, and his younger brothers Yusuf and Salih Abu Dani were installed in I'billin and Arraba, respectively.[71] Zahir appointed his eldest son Salibi as the multazim of Tiberias.[70] Salibi was killed in 1773 fighting alongside Ali Bey's forces in Egypt.[72] His death deeply distressed Zahir, who was around 80 years old at the time.[73] He appointed Uthman in Kafr Kanna then Shefa-'Amr,[71] Abbas in Nazareth, Ali in Safad, and Ahmad in Saffuriya. Ahmad replaced Salibi in Tiberias as well, and also conquered Ajlun and Salt in Transjordan. In addition, Ahmad was given authority over Deir Hanna after Sa'd's death. Zahir appointed his nephew Ayyub al-Karimi in Jaffa and Gaza,[71] while al-Dinkizli was made multazim in Sidon in 1774. The appointment of Zahir's relatives and close associates was meant to ensure the efficient administration of his expanding realm and the loyalty of his circle. Among their chief functions was to ensure the supply of cotton to Acre. It is not clear if these posts were recognized by the Ottoman government.[70]

Zahir had an aide who jointly served in the capacity of mudabbir (manager) and wazir (vizier) to assist him throughout much of his rule in matters of finance and correspondence.[74] This official had always been a Melkite (local Greek Catholic). His first wazir was Yusuf al-Arqash,[71] followed by Yusuf Qassis in 1749. Qassis continued in this role until the early 1760s when he was arrested for attempting to smuggle wealth he had accumulated during his service to Malta.[74] He was succeeded by Ibrahim Sabbagh,[71] who had served as a personal physician for Zahir in 1757 when he replaced Zahir's longtime physician Sulayman Suwwan. Suwwan was a local Greek Orthodox Christian and when he failed to properly treat Zahir during a serious illness in 1757, Qassis used the opportunity to replace him with Sabbagh, a friend and fellow Melkite.[74] Sabbagh became the most influential figure in Zahir's administration, particularly as Zahir grew old. This caused consternation among Zahir's sons as they viewed Sabbagh to be a barrier between them and their father and an impediment to their growing power in Zahir's territory. Sabbagh was able to gain increased influence with Zahir largely because of the wealth he amassed through his integral role in managing Zahir's cotton monopoly. Much of this wealth was acquired through Sabbagh's own deals where he would purchase cotton and other cash crops from the local farmers and sell them to the European merchants in the Syria's coastal cities and to his Melkite partners in Damietta, Egypt.[75] Sabbagh served other important roles as well, including as Zahir's political adviser, main administrator and chief representative with European merchants and Ottoman provincial and imperial officials.[76]

There were other officials in Zahir's civil administration in Acre, including chief religious officials, namely the mufti and the qadi. The mufti was the chief scholar among the ulama (Muslim scholarly community) and oversaw the interpretation of Islamic law in Zahir's realm. He was appointed by the Sublime Porte, but Zahir managed to maintain the same mufti for many years at a time in contrast with the typical Syrian province which saw its mufti replaced annually. Zahir directly appointed the qadi from Palestine's local ulama, but his judicial decisions had to be approved by the qadi of Sidon.[76] Zahir had a chief imam, who in the last years of his rule was Ali ibn Khalid al-Shaabi.[77] An agha was also appointed to supervise the customs payments made by the European merchants in Acre and Haifa.[76]

Zahir's initial military forces consisted of his Zaydani kinsmen and the local inhabitants of the areas he ruled. They numbered about 200 men in the early 1720s, but grew to about 1,500 in the early 1730s. During this early period of Zahir's career, he also had the key military backing of the Bani Saqr and other Bedouin tribes. As he consolidated his hold over Galilee, his army rose to over 4,000 men, many of the later recruits being peasants who supported Zahir for protecting them against Bedouin raids. This suppression of the Bedouin in turn caused the tribes to largely withdraw their military backing of Zahir. The core of his private army were the Maghrebi mercenaries. The Maghrebis' commander, Ahmad Agha al-Dinkizli, also served as Zahir's top military commander from 1735 until al-Dinkizli's defection during the Ottoman siege of Acre in 1775. From the time Zahir reconciled with Sheikh Nasif al-Nassar of Jabal Amil in 1768 until most of the remainder of his rule, Zahir also had the support of Nasif's roughly 10,000 Metawali cavalrymen. However, the Metawalis did not aid Zahir during the Ottoman offensive of 1775. Zahir's fortified villages and towns were equipped with artillery installments and his army's arsenal consisted of cannons, matchlock rifles, pistols and lances. Most of the firearms were imported from Venice or France, and by the early 1770s, from the Russian imperial navy.[78]

General security

According to biographer Ahmad Hasan Joudah, the two principal conditions Zahir established to foster his sheikhdom's prosperity and its survival were "security and justice".[79] Prior to Zahir's consolidation of power, the villages of northern Palestine were prone to Bedouin raids and robberies and the roads were under constant threat from highway robbers and Bedouin attacks. Although following the looting raids, the inhabitants of these agrarian villages were left destitute, the Ottoman provincial government would nonetheless attempt to collect from them the miri (hajj tax). To avoid punitive measures for not paying the miri, the inhabitants would abandon their villages for safety in the larger towns or the desert. This situation hurt the economy of the region as the raids sharply reduced the villages' agricultural output, the government-appointed mutasallims (tax farmers) could not collect their impositions, and trade could not be safely conducted due to insecurity on the roads.[79]

By 1746, however, Zahir had established order in the lands he ruled.[80] He managed to co-opt the dominant Bedouin tribe of the region, the Bani Saqr, which greatly contributed to the establishment of security in northern Palestine.[81] Moreover, Zahir charged the sheikhs of the towns and villages of northern Palestine with ensuring the safety of the roads in their respective vicinity and required them to compensate anyone who was robbed of his/her property. General security reached a level whereby "an old woman with gold in her hand could travel from one place to another without fear or danger", according to biographer Mikhail Sabbagh.[82]

This period of calm that persisted between 1744 and 1765 greatly boosted the security and economy of Galilee. The security established in the region encouraged people from other parts of the Ottoman Empire to immigrate to Galilee.[29] Conflict between the local clans and between Zahir and his sons remained limited to periodic clashes, while there were no attacks against Zahir's domain from outside forces.[33] While Zahir used force to strengthen his position in the region, the local inhabitants generally took comfort in his rule, which historian Thomas Philip described as "relatively just and reasonably fair".[12] According to Richard Pococke who visited the area in 1737, the local people had great admiration for Zahir, especially for his war against bandits on the roads.[83]

Economic policies

In addition to providing security, Zahir and his local deputies adopted a policy of aiding the peasants cultivate and harvest their farmlands to further guarantee the steady supply of agricultural products for export. These benefits included loans to peasants and the distribution of free seeds.[82] Financial burdens on the peasants were also reduced as Zahir offered tax relief during drought seasons or when the harvest seasons were poor.[29][84] This same tax relief was extended to newcomers who sought to begin cultivating new farmlands.[29] Moreover, Zahir assumed responsibility for outstanding payments the peasants owed to merchants from credit-based transactions if the merchants could provide proof of unsatisfactory payment.[82] According to historian Thomas Philipp, Zahir "had the good business sense not to exploit peasants to the point of destruction, but kept his financial demands to a more moderate level."[29] He regularly paid the Ottoman authorities their financial dues, ensuring a degree of stability in his relationship with the sultanate.[85]

When Zahir conquered Acre, he transformed it from a decaying village into a fortified market hub for Palestinian products, including silk, wheat, olive oil, tobacco and cotton, which he exported to Europe.[85][86] With cotton in particular, Zahir was able to monopolize the market for it and its foreign export. He did business with European merchants based in Galilee's ports, who competed with one another for the cotton and grain cultivated in the rural villages under Zahir's dominion or influence in Galilee's hinterland and Jabal Amil.[87] Previously, European merchants made direct transactions with local cotton growers, but Zahir, with the help of Ibrahim Sabbagh, put an end to this system of commerce by making himself the middleman between the merchants and the growers living under his rule. This allowed him to both monopolize cotton production and the merchants' price for the product.[88] Zahir's designation of prices for the local cash crops also prevented "exploitation" of the peasants and local merchants by European merchants and their "manipulation of the prices", according to Joudah.[74] This caused financial losses to the European merchants who lodged numerous complaints to the French and English ambassadors to the Sublime Porte. A formal agreement to regulate commerce between Zahir and the European merchants was reached in 1753.[74] Zahir further encouraged trade by offering local merchants interest-free loans.[82]

The high European demand for the product enabled Zahir to grow wealthy and finance his autonomous sheikhdom. This control of the cotton market also allowed him to gain unofficial control over all of the Sidon Eyalet, outside the city of Sidon itself.[89] With mixed success, Zahir attempted to have French merchant ships redirected from the ports of Tyre and Sidon to Haifa instead, in order to benefit from the customs fees he could exact.[90] The city of Acre underwent an economic boom as a result of its position in the cotton trade with France,[1] and became the fortified headquarters of Zahir's sheikhdom.[91]

Relationship with religious minorities

Zahir maintained tolerant policies and encouraged the involvement of religious minorities in the local economy. As part of his larger efforts to enlarge the population of Galilee,[92] Zahir invited Jews to resettle in Tiberias around 1742,[93] along with Muslims.[92] Zahir did not consider Jews to be a threat to his rule and believed that their connections with the Jewish diaspora would encourage economic development in Tiberias, which the Jews considered particularly holy. His tolerance towards the Jews, the cuts in taxes levied on them, and assistance in the construction of Jewish homes, schools and synagogues, helped foster the growth of the Jewish community in the area.[94] The initial Jewish immigrants came from Damascus and were later followed by Jews from Aleppo, Cyprus and Smyrna.[95] Many Jews in Safad, which was governed by Zahir's son Ali, moved to Tiberias in the 1740s to take advantage of better opportunities in that city, which at the time was under Zahir's direct rule.[92] The villages of Kafr Yasif and Shefa-'Amr also saw new Jewish communities spring up under Zahir's rule.[96]

Zahir encouraged local Christian settlement in Acre,[97] in order to contribute to the city's commercial dynamism in trade and manufacturing.[98] Christians grew to become the largest religious group in the city by the late 18th century.[97] Zahir's territory became a haven for Melkite and Greek Orthodox Christians from other parts of Ottoman Syria who migrated there for better trade and employment opportunities. In Nazareth, the Christian community prospered and grew under Zahir's rule, and saw an influx from the Maronite and Greek Orthodox communities of Lebanon and Transjordan, respectively.[99] The Melkite patriarch lived in Acre between 1765 and 1768.[100] Along with the Jews, the Christians contributed to the economy of Zahir's sheikhdom in a number of ways, including the relative ease with which they were able to deal with European merchants, the networks of support many of them maintained in Damascus or Istanbul, and their role in service industries.[101]

Zahir allowed the Franciscan community of Nazareth to build churches in 1730, 1741 and 1754 on sites Christians associated with Jesus's life. He allowed the Greek Orthodox community to build St. Gabriel's Church over a ruined Crusader church in Nazareth,[99] and in 1750 they enlarged St. George's Church. The largest Christian community in Acre, the Melkites, built the largest church in the city, St. Andrew's Church, in 1764, while the Maronites built St. Mary's Church for their congregation in 1750. As a testament to the prosperity that the Christians enjoyed under Zahir's rule, no further churches were built under the auspices of Zahir's less tolerant successors.[100]

A strong relationship existed between Zahir and the Shia Muslim peasants of Jabal Amil and their sheikhs. Zahir maintained law and order in Jabal Amil, while leaving its mostly Shia inhabitants to their own devices. The Shia also benefited economically from Zahir's monopoly of the cotton industry and their sheikhs provided him men of great military skill to support his struggle against the Ottoman authorities.[89] Zahir was a key backer of the Shia in their war with the Druze Jumblatt clan and the Shihab dynasty under Mulhim Shihab,[102] and likewise, Shia forces were critical to the defense of Zahir's sheikhdom against expeditions by the Ottoman governor of Damascus in 1771 and 1772.[89]

The relationship between Zahir and the rural sheikhs of the Druze of Mount Lebanon under the Shihab dynasty were mixed. While Sheikh Mansur Shihab of Chouf allied himself with Zahir, his nephew and rival, Yusuf Shihab of the Tripoli region remained supportive of the Ottomans.[103] Owing largely to the conflict between Zahir and the Druze emirs of Mount Lebanon, he Druze of Galilee did not fare well under Zahir and his Zaydani clan. In the oral traditions of Galilee's Druze inhabitants, Zahir's reign was synonymous with oppression. During this period, many Druze villages were either destroyed or abandoned and there was a partial Druze exodus from Galilee, particularly from the villages around Safad, to the Hauran region east of the Jordan River.[104]

Family

Zahir's clan belonged to the Qaisi political faction in the centuries-long struggle between the Qais and Yaman confederations.[6] The Ma'an and Shihab dynasties, who ruled Mount Lebanon (and often Galilee) semi-autonomously, also belonged to the Qaisi faction.[105] For the most part, Zahir respected the socio-political system that prevailed in the region he ruled. The alliances between him and local notables were bolstered by a network of marriages between the influential families of the area, including Zahir's Zaydani clan.[106] Zahir's own marriages were politically advantageous as they allowed him to consecrate his rule over certain areas or his relationships with certain Bedouin tribes, local clans or urban notables.[82] Zahir had five wives during his lifetime.[107] Among his wives was a woman from the Sardiyah, a Bedouin tribe active in Transjordan and Palestine.[108] Zahir was also married to a daughter of Sayyid Muhammad, a wealthy religious notable from Damascus,[10] a daughter of the mukhtar (headman) of Bi'ina,[13] and a daughter of the mukhtar of Deir al-Qassi.[19]

Zahir had eight sons from his wives,[7] and according to Tobias Smollett, a daughter as well.[107] His sons, from eldest to youngest, were Salibi, Ali, Uthman, Sa'id, Ahmad, Salih, Sa'd al-Din and Abbas.[7] His daughter's husband's name was Karim al-Ayyubi,[107] who was also Zahir's cousin.[71] By 1773, Zahir had a total of 272 children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.[107]

As Zahir consolidated his power and reduced external threats to his rule in the 1760s, his sons aspired for more influence and ultimately fought against their father and each other in order to secure their place as Zahir's successor. Besides support from elements of the Zaydani clan, Zahir's sons maintained their own power bases, largely derived from their mothers' clans, and also made their own alliances with other powerful actors in the region. Zahir was victorious in the many conflicts he had with his sons, but their frequent dissent weakened his rule and played a contributory role to his downfall in 1775.[27] Prior to his sons' individual rebellions, Zahir had eliminated other relatives who challenged his power.[27]

Legacy

Zahir's rule radically changed the landscape of Galilee. With the restoration and re-fortification of Acre and the establishment of the secondary port city of Haifa, Galilee significantly strengthened its ties with the Mediterranean world.[109] Following Zahir's death, his successor Jazzar Pasha maintained the cotton monopoly Zahir had established and Galilee's economy remained almost completely dependent on the cotton trade. The region prospered for decades, but with the rise of the cotton market in the southern United States during the early-mid 19th century, European demand shifted away from Palestine's cotton and because of its dependency on the crop, the region experienced a sharp economic downturn from which it could not recover. The cotton crop was largely abandoned, as were many villages, and the peasantry shifted its focus to subsistence agriculture.[110]

In the late 19th century, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Claude Reignier Conder wrote that the Ottomans had successfully destroyed the power of Palestine's indigenous ruling families who "had practically been their own masters" but had been "ruined so that there is no longer any spirit left in them".[111] Among these families were the "proud race" of Zahir, which was still held in high esteem, but was powerless and poor.[111] Zahir's modern-day descendants in Galilee use the surname "Dhawahri" or "al-Zawahirah" in Zahir's honor. The Dhawahri clan constitute one of the traditional elite Muslim clans of Nazareth, alongside the Fahum, Zu'bi and 'Onallas families.[112] Other villages in Galilee where descendants of Zahir's clan live are Bi'ina and Kafr Manda and, prior to its 1948 destruction, al-Damun. Many of the inhabitants of modern-day northern Israel, particularly the towns and villages where Zahir or his family left an architectural legacy, hold Zahir in high regard.[113]

Although he was mostly overlooked by historians of the Middle East, some scholars view Zahir's rule as a forerunner to Palestinian nationalism.[114] Among these scholars is Karl Sabbagh, who asserts the latter view in his book Palestine: A Personal History, which was widely reviewed in the British press in 2010.[115] Zahir was gradually integrated into Palestinian historiography.[116] In Murad Mustafa Dabbagh's Biladuna Filastin (1965), a multi-volume work about Palestine's history, Zahir is referred to as the "greatest Palestinian appearing in the eighteenth century".[113] The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) radio station, Voice of Palestine, broadcast a series about Zahir in 1966, praising him as a Palestinian national hero who fought against Ottoman imperialism.[113] Zahir is considered by many Arab nationalists as a pioneer of Arab liberation from foreign occupation.[117] According to Joudah

However historians may look at Shaykh Zahir al-'Umar and his movement, he is highly respected by the Arabs of the East. In particular the Palestinians consider him a national hero who struggled against Ottoman authority for the welfare of his people. This praise is reflected in the recent academic, cultural and literary renaissance within Palestinian society that has elevated Zahir and his legacy to near-iconic status. These re-readings are not always bound to historical objectivity but are largely inspired by the ongoing consequences of the Nakba. Still it is precise to say that Shaykh Zahir had successfully established an autonomous state, or a "little Kingdom," as Albert Hourani called it, in most of Palestine for over a quarter of a century.[2]

Building works

Zahir and his family built fortresses, watchtowers, warehouses, and khans (caravanserais). These buildings improved the domestic administration and general security of Galilee. Today, many of these structures are in a state of disrepair and remain outside the scope of Israel's cultural preservation laws.[109]

In Acre, Zahir rebuilt the Crusader-era walls and built on top of various Crusader and Mamluk structures in the city. Among these were the caravanserais of Khan al-Shawarda and its Burj al-Sultan tower and Khan al-Shunah.[118] In 1758, he commissioned the construction of the al-Muallaq Mosque,[119] He also built the Seraya government house in Nazareth,[112] which served as that city's municipal headquarters until 1991.[120] In Haifa, which Zahir founded, he built a wall with four towers and two gates around the new settlement. Within Haifa, he built the Burj al-Salam fortress, a small mosque, a customs building, and a government residence (saraya).[121] In Tiberias, he commissioned the building of a citadel (now ruined) and the al-Amari Mosque. The latter was built with alternating white and black stone, typical of the architectural style of Zahir's building works, and a minaret.[95]

Fortifications and other structures were built in the rural villages under Zahir's control.[114] In Deir Hanna, Zahir's brother Sa'd built a large fortress and an adjacent mosque, both of which were severely damaged during a siege by Jazzar Pasha in 1776.[122] In Khirbat Jiddin, he rebuilt the demolished Crusader fortress with the addition of a mosque and hamaam (bathhouse). The mosque was destroyed by Israeli forces when the village was captured during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[123] In Shefa-'Amr, Zahir's son Uthman built a large fortress with four towers, of which one remains standing.[124] Another of his sons, Ahmad, rebuilt the Crusader fortress in Saffuriya.[125]

In Tibnin, in modern-day Lebanon,[126] and in Safad, Zahir or his son Ali had Crusader-era fortresses rebuilt.[127] Zahir fortified the village of Harbaj, although the village and its fort were in ruins by the late 19th century.[128] At Tabgha on the Sea of Galilee, Zahir built five fountains, one of which remained standing by the 19th century. That remaining fountain was the largest of its kind in Galilee.[129] In the village of I'billin, Zahir's brother Yusuf built fortifications and a mosque.[130] The I'billin fortress was later used as the headquarters of Aqil Agha, the 19th century semi-autonomous Arab sheikh of Galilee.[131]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Philipp, ed. Bosworth, "Ẓāhir al- ʿUmar al-Zaydānī".

- 1 2 Joudah, Ahmad (2015). "Zahir al-'Umar and the First Autonomous Regime in Ottoman Palestine (1744-1775)" (PDF). Jerusalem Quarterly. Institute for Palestine Studies (63–64): 84–85.

- 1 2 3 4 Pappe, 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 30.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 29.

- 1 2 Harris, 2012, p. 114

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 Philipp, 2001, p. 31

- ↑ Moammar, 1990, pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 Philipp, 2001, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, pp. 22-23

- 1 2 3 4 Philipp, 2001, p. 32

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Philipp, 2001, p. 33

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 28.

- ↑ Doumani, 1995, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 31.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 34

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 24.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Moammar, 1990, pp. 71–82.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 37

- ↑ Khalidi, 1992, p. 351.

- 1 2 Philipp, 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Raymond, 1990, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joudah, 1987, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 Philipp, 2001, p. 36

- 1 2 3 4 5 Philipp, 2001, p. 38.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 27.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 Philipp, 2001, p. 39

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 143.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 48.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 51.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 52.

- ↑ Yazbak, 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ Joudah, pp. 52–53.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 56.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 40

- 1 2 3 4 Philipp, 2001, p. 41

- 1 2 Rogan, 2009, p. 50

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 70.

- 1 2 Rogan, 2009, p. 51

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 81.

- ↑ Doumani, 1995, p. 95

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 84.

- 1 2 Doumani, 1995, p. 96

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 88.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 85.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 86

- 1 2 3 4 Philipp, 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ D. Crecelius: "Egypt's Reawakening Interest in Palestine During the Regimes of Ali Bey al-Kabir and Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dahab: 1760–1775". In Kushner, 1986, p. 247

- ↑ D. Crecelius: "Egypt's Reawakening Interest in Palestine During the Regimes of Ali Bey al-Kabir and Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dahab: 1760–1775". In Kushner, 1986, p. 248

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 3 Philipp, 2001, p. 43.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 137

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 112.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joudah, 1987, p. 114.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 115.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 116.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 117.

- ↑ Thackston, 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Volney, 1788, p. 91

- ↑ Volney, 1788, p. 133

- 1 2 3 Philipp, 2001, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joudah, 1987, p. 127.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 110.

- ↑ Sabbagh, 2006, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joudah, 1987, p. 39.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 128.

- ↑ Reichmuth, 2009, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 129.

- 1 2 Joudah, 1987, p. 37.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Philipp, 1992, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joudah, 1987, p. 38.

- ↑ Pococke, 1745, vol 2, p. 69

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 123.

- 1 2 Hitti, 1951, p. 688.

- ↑ Lehmann, 2014, p. 31

- ↑ D. Crecelius: "Egypt's Reawakening Interest in Palestine During the Regimes of Ali Bey al-Kabir and Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dahab: 1760–1775". In Kushner, 1986, p. 249

- ↑ Doumani, 1995, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 Shanahan, 2005, p. 23

- ↑ Yazbak, 1998, p. 13

- ↑ Doumani, 1995, p. 99

- 1 2 3 Barnay, 1992, p. 15

- ↑ Moammar, 1990, p. 70.

- ↑ Barnay, 1992, p. 148

- 1 2 Sabbagh, 2006, p. 38

- ↑ Barnay, 1992, p. 156

- 1 2 Pringle, 2009, p. 30

- ↑ Dumper, 2007, p. 6

- 1 2 Emmett, 1995, p. 22

- 1 2 Philipp, 2001, p. 177

- ↑ D. R. Khoury: "Political Relations Between City and State in the Middle East 1700–1850", in Sluglett, 2008, p. 94

- ↑ Winter, 2010, p. 132

- ↑ Harris, 2012, p. 120

- ↑ Firro, 1992, p. 46

- ↑ Harris, 2012, p. 113.

- ↑ Ajami, 1986, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 4 Smollet, 1783, p. 282.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 41

- 1 2 Orser, 1996, p. 473

- ↑ Orser, 1996, p. 474

- 1 2 Scholch, 1984, p. 474.

- 1 2 Srouji, 2003, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 118.

- 1 2 Baram, 2007, p. 28

- ↑ LeBor, Adam (2006-06-02). "Land of My Father". The Guardian.

- ↑ Philipp, 2001, p. 39.

- ↑ Moammar, 1990, preface

- ↑ Sharon, 1997, p. 28

- ↑ Sharon, 1997, p. 38

- ↑ Seraya, Nazareth Cultural and Tourism Association

- ↑ Yazbak, 1998, p. 15

- ↑ Sharon, 2004, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Masalha, 2013, p. 178

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 272

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 338

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 207–208

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 248

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 285

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, pp. 376–377.

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 269.

- ↑ Schölch, 1984, p. 463.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zahir al-Umar. |

- Ajami, Fouad (1986). The Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801465079.

- Baram, Uzi (2007). "Expressions of Social Identity". In Mark LeVine. Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4639-4.

- Barnai, Jacob (1992). Naomi Goldblum (Translator), ed. The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: Under the Patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0572-7.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, H. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Doumani, Beshara (1995). Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus. University of California Press.

- Dumper, Michael (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Emmett, Chad F. (1995). Beyond the Basilica: Christians and Muslims in Nazareth. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-20711-7.

- Firro, Kais (1992). A History of the Druzes. 1. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09437-7.

- Harris, William (2012). Lebanon: A History, 600-2011. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518111-1.

- Hitti, Phillip K. (1951). History of Syria, Including Lebanon and Palestine. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-119-1.

- Joudah, Ahmad Hasan (1987). Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir Al-ʻUmar. Kingston Press. ISBN 978-0-940670-11-2.

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Kushner, David, ed. (1986). Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period: Political, Social, and Economic Transformation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-07792-8.

- Lehmann, Matthias (2014). Emissaries from the Holy Land: The Sephardic Diaspora and the Practice of Pan-Judaism in the Eighteenth Century. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-8965-3.

- Masalha, Nur (2013). The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54465-4.

- Moammar, Tawfiq (1990). Zahir Al Omar. Nazareth: Al Hakim Printing Press.

- Orser, Charles E. (1996). Images of the Recent Past: Readings in Historical Archaeology. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7619-9142-7.

- Pappe, Ilan (2010). The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty: The Husaynis 1700–1968. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-460-4.

- Philipp, Thomas (2001). Acre: The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian City, 1730–1831. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50603-8.

- Philipp, Thomas (2015). ""Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar al-Zaydānī". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). Brill Online.

- Pococke, Richard (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Pringle, Denys (2009). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The cities of Acre and Tyre with Addenda and Corrigenda to Volumes I-III. IV. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85148-0.

- Raymond, Andre (1990). Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée. Édisud.

- Rogan, Eugene L. (2009). The Arabs: A History. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03248-8.

- Sabbagh, Karl (2006). Palestine: History of a Lost Nation. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. ISBN 978-1-55584-874-3.

- Shanahan, Roger (2005). Shi'a of Lebanon: Clans, Parties and Clerics. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-678-1.

- Sharon, Moshe (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. 1. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- Sharon, Moshe (2004). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, D–F. 3. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13197-3.

- Sluglett, Peter, ed. (2008). The Urban Social History of the Middle East, 1750–1950. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-5063-8.

- Smollet, Tobias George (1783). The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature. 55. W. Simpkin and R. Marshall.

- Srouji, Elias S. (2003). Cyclamens from Galilee: Memoirs of a Physician from Nazareth. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 978-0-595-30304-5.

- Thackston, Wheeler McIntosh (1988). Murder, Mayhem, Pillage, and Plunder: The History of the Lebanon in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Mikhayil Mishaqa (1800–1873). SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-712-9.

- Volney, Constantin-Francois (1788). "XXV: Summary of the History of Daher, Son of Omar, Who Governed Acre from 1750 to 1776". Travels Through Syria and Egypt, in the Years 1783, 1784, and 1785: Containing the Present Natural and Political State of Those Countries, Their Productions, Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce; with Observations on the Manners, Customs, and Government of the Turks and Arabs. G.G.J. and J. Robinson.

- Winter, Stefan (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48681-1.

- Yazbak, Mahmoud (1998). Haifa in the Late Ottoman Period, A Muslim Town in Transition, 1864–1914. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 90-04-11051-8.

| Preceded by Darwish Pasha al-Kurji |

Wali of Sidon 1771—1775 (de facto) |

Succeeded by Jazzar Pasha |

| Preceded by Umar al-Zaydani |

Multazim of Tiberias 1730–1750s |

Succeeded by Salibi al-Zahir |

| Preceded by Sa'd al-Umar |

Multazim of Deir Hanna 1761–1767 |

Succeeded by Ali al-Zahir |