37th United States Congress

| 37th United States Congress | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

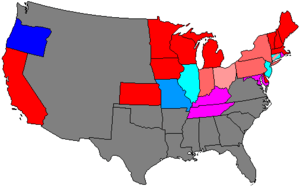

The Thirty-seventh United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1861 to March 4, 1863, during the first two years of Abraham Lincoln's presidency.[1] The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the Seventh Census of the United States in 1850. Both chambers had a Republican majority.

Major events

- March 4, 1861: Republican pluralities are seated in Senate and House, becoming governing majorities in both Houses given vacancies among Southerners. Louisiana has 2 of 4 representatives remaining. Although represented in the Confederate Congress, Missouri and Kentucky remained with full delegations in the 37th Congress.[2][3]

- March 4, 1861: Abraham Lincoln, certified as constitutionally elected president by the 36th Congress, is duly inaugurated President of the United States.

- April 12–14, 1861: Battle of Fort Sumter, Civil War began

- April 19, 1861: Union blockade of the South begins at Fort Monroe, Virginia[4]

- April 27, 1861: President Lincoln suspends habeas corpus from Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia[5] and called up 75,000 militia.

- May 6, 1861: Arkansas Secession Convention enacted an Ordinance of Secession.[6]

- May 20, 1861: North Carolina Secession Convention enacted an Ordinance of Secession.[7]

- May 23, 1861: Virginia popular referendum ratified Ordinance of Secession.[8] 5 of 12 U.S. Representatives remained.[9] Two senators from the "Restored Government of Virginia" replaced the two who withdrew.

- June 8, 1861: Tennessee popular referendum ratified Ordinance of Secession.[10] 3 of 10 U.S. Representatives remain.[9] One Senator, Andrew Johnson, remained.

- July 21, 1861: First Battle of Bull Run Union approach to Richmond is repulsed.

- September 17, 1862: Battle of Antietam rebel invasion into Maryland is repulsed.

- September 22, 1862: Emancipation Proclamation ordered, to begin January 1, 1863

- November 1862: United States House of Representatives elections, 1862 and United States Senate elections, 1862 and 1863: Democrats gained 31 House seats to 31% and lost 5 Senate seats to 19%.[11]

Two special sessions

The Senate, a continuing body, was called into special session by President Buchanan, meeting in March 4 to March 28, 1861.[12] The border states and Texas were still represented. Shortly after the Senate session adjourned, Fort Sumter was attacked. The immediate results were to draw four additional states[13] "into the confederacy with their more Southern sisters", and Lincoln called Congress into extraordinary session on July 4, 1861. The Senate confirmed calling forth troops and raising money to suppress rebellion as authorized in the Constitution.[14]

Both Houses then duly met July 4, 1861. Seven states which would send representatives held their state elections for Representative over the months of May to June 1861.[15] Members taking their seats had been elected before the secession crisis, during the formation of the Confederate government, and after Fort Sumter.[9]

Once assembled with a quorum in the House, Congress approved Lincoln's war powers innovations as necessary to preserve the Union.[16] Following the July Federal defeat at First Manassas, the Crittenden Resolution[17] asserted the reason for "the present deplorable civil war." It was meant as an address to the nation, especially to the Border States at a time of U.S. military reverses, when the war support in border state populations was virtually the only thing keeping them in the Union.[18]

Following resignations and expulsions occasioned by the outbreak of the Civil War, five states had some degree of dual representation in the U.S and the C.S. Congresses. Congress accredited Members elected running in these five as Unionist (19), Democratic (6), Constitutional Unionist (1) and Republican (1). All ten Kentucky and all seven Missouri representatives were accepted. The other three states seated four of thirteen representatives from Virginia, three of ten Tennesseans, and two of four from Louisiana.[19]

The Crittenden Resolution declared the civil war "… has been forced upon the country by the disunionists of the southern States…" and it would be carried out for the supremacy of the Constitution and the preservation of the Union, and, that accomplished, "the war ought to cease". Democrats seized on this document, especially its assurances of no conquest or overthrowing domestic institutions (emancipation of slaves).[18]

|

Slaves and slavery

Congressional policy and military strategy were intertwined. In the first regular March session, Republicans superseded the Crittenden Resolution, removing the prohibition against emancipation of slaves.[18]

In South Carolina, Gen. David Hunter, issued a General Order in early May 1861 freeing all slaves in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. President Lincoln quickly rescinded the order, reserving this "supposed power" to his own discretion if it were indispensable to saving the Union.[20] Later in the same month without directly disobeying Lincoln's prohibition against emancipation, General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe Virginia declared slaves escaped into his lines as "contraband of war", that is, forfeit to their rebel owners.[21] On May 24, Congress followed General Butler's lead, and passed the First Confiscation Act in August, freeing slaves used for rebellion.[22]

In Missouri, John C. Frémont, the 1856 Republican nominee for President, exceeded his authority as a General, declaring that all slaves held by rebels within his military district would be freed.[22] Republican majorities in Congress responded on opening day of the December Session. Sen. Lyman Trumbull introduced a bill for confiscation of rebel property and emancipation for their slaves. "Acrimonious debate on confiscation proved a major preoccupation" of Congress.[18] On March 13, 1862, Congress directed the armies of the United States to stop enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. The next month, the Congress abolished slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for loyal citizens. An additional Confiscation Act in July declared free all slaves held by citizens in rebellion, but it had no practical effect without addressing where the act would take effect, or how ownership was to be proved.[23]

Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued September 22, 1862.[23] It became the principal issue before the public in the mid-term elections that year for the 38th Congress. But Republican majorities in both houses held (see 'Congress as a campaign machine' below), and the Republicans actually increased their majority in the Senate.[24]

On January 1, 1863, the war measure by executive proclamation directed the army and the navy to treat all escaped slaves as free when entering Union lines from territory still in rebellion. The measure would take effect when the escaped slave entered Union lines and loyalty of the previous owner was irrelevant.[25] Congress passed enabling legislation to carry out the Proclamation including "Freedman's Bureau" legislation.[26] The practical effect was a massive internal evacuation of Confederate slave labor, and augmenting Union Army teamsters, railroad crews and infantry for the duration of the Civil War.

|

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

Congress assumed watchdog responsibilities with this and other investigating committees.

The principle conflict between the president and congress was found in the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Eight thick volumes of testimony were filled with investigations of Union defeats and contractor scandals.

They were highly charged with partisan opinions "vehemently expressed" by chair Benjamin Wade of Ohio, Representative George Washington Julian of Indiana, and Zachariah Chandler of Michigan.[27]

Sen. Chandler, who had been one of McClellan's advocates promoting his spectacular rise,[28] particularly documented criticism of McClellan's Peninsular Campaign with its circuitous maneuvering, endless entrenchment and murderous camp diseases. It led to support for his dismissal.

A congressional committee could ruin a reputation, without itself having any military expertise. It would create the modern Congressional era in which generals fought wars with Congress looking over their shoulders, "and with public opinion following closely behind."[27]

Republican Platform goals

Republican majorities in both houses, apart from pro-union Democrats, and without vacant southern delegations, were able to enact their party platform. These included the Legal Tender Act, February 20, 1862, and increases in the tariff that amounted to protective tariffs. The Homestead Act, May 20, 1862, for government lands, and the Morrill Land Grant Act, July 2, 1862, for universities promoting practical arts in agriculture and mining, had no immediate war purpose. But they would have long range effects, as would the Pacific Railroad Act, July 1, 1862, for a transcontinental railroad.[29]

Treasury innovations were driven by Secretary Salmon P. Chase and necessity of war. The Income Tax of 1861, numerous taxes on consumer goods such as whiskey, and a national currency all began in Civil War Congresses.[29]

Congress as election machinery

Member's floor speeches were not meant to be persuasive, but for publication in partisan newspapers. The real audience was the constituents back home. Congressional caucuses organized and funded political campaigns, publishing pamphlet versions of speeches and circulating them by the thousands free of postage on the member's franking privilege. Party congressional committees stayed in Washington during national campaigns, keeping an open flow of subsidized literature pouring back into the home districts.[30]

Nevertheless, like other Congresses in the 1850s and 1860s, this Congress would see less than half of its membership reelected.[31] The characteristic turmoil found in the "3rd Party Period, 1855-1896" stirred political party realignment in the North even in the midst of civil war. In this Congress, failure to gain nomination and loss at the general election together accounted for a Membership turnover of 25%.[32]

This Congress in the generations cycle

This first Civil War Congress was one of the last with a plurality of members drawn from the "Transcendental" generation born between 1792 and 1821.[33] They accounted for 87% of the national leadership, with 12% from the upcoming Gilded Age, and only 1% from the older Compromise Generation.[34] As an age cohort, they were idealistic and exalted "inner truth" on both sides of the Civil War, with neither side prepared to compromise its principles. Those few Compromisers left with a voice were pushed to the side. Representative Thaddeus Stevens was typical of his Transcendentalist generations northern expression: "Instruments of war are not selected on account of their harmlessness ... lay waste to the whole South."[35]

Major legislation

- August 5, 1861: Revenue Act of 1861, Sess. 1, ch. 45, 12 Stat. 292

- August 6, 1861: Confiscation Act of 1861, Sess. 1, ch. 60, 12 Stat. 319

- February 25, 1862: Legal Tender Act of 1862, Sess. 2, ch. 33, 12 Stat. 345

- April 16, 1862: Slavery in the District of Columbia abolished, Sess. 2, ch. 54, 12 Stat. 376

- May 15, 1862: An Act to Establish a Department of Agriculture, Sess. 2, ch. 72, 12 Stat. 387

- May 20, 1862: Homestead Act, Sess. 2, ch. 75, 12 Stat. 392

- June 19, 1862: An Act to secure Freedom to all persons within the Territories of the United States, Sess. 2, ch 111, 12 Stat. 432

- July 1, 1862: Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, Sess. 2, ch. 126, 12 Stat. 501

- July 1, 1862: Revenue Act of 1862, Sess. 2, ch. 119, 12 Stat. 432

- July 1, 1862: Pacific Railway Act, Sess. 2, ch. 120, 12 Stat. 489

- July 2, 1862: Morrill Land Grant Colleges Act, Sess. 2, ch. 130, 12 Stat. 503

- July 17, 1862: Militia Act of 1862, Sess. 2, ch. 201, 12 Stat. 597

- February 25, 1863: National Banking Act, Sess. 3, ch 58, 12 Stat. 665

- March 2, 1863: False Claims Act, Sess. 3, ch. 67, 12 Stat. 696

- March 3, 1863: Enrollment Act, Sess. 3, ch. 75, 12 Stat. 731

- March 3, 1863: Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, Sess. 3, ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755

- March 3, 1863: Tenth Circuit Act, 12 Stat. 794

States admitted and seceded and territories organized

States admitted

- December 31, 1862: West Virginia admitted, Sess. 3, ch. 6, 12 Stat. 633, pending a presidential proclamation. (It became a state on June 20, 1863)

Territories organized or changed

- July 14, 1862: Nevada Territory extended and Utah Territory reduced, Sess. 2, ch. 12, 12 Stat. 575

- February 24, 1863: Arizona Territory organized, Sess. 3, ch. 56, 12 Stat. 664

- March 3, 1863: Idaho Territory organized, Sess. 3, ch. 117, 12 Stat. 808

Rebellion

Congress did not accept secession. Most of the Representatives and Senators from states that attempted to secede left Congress; those who took part in the rebellion were expelled.

- Secessions declared during previous Congress: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.

- Secessions declared during this Congress:

- April 17, 1861: Virginia[37] (The pro-Union Restored Government of Virginia's two Senators were seated, along with duly elected Representatives for VA 1, 7, 10, 11 and 12, five of its 13 representatives in the House.[36])

- May 6, 1861: Arkansas[38]

- May 20, 1861: North Carolina[39]

- June 8, 1861: Tennessee[40][41] (Sen. Andrew Johnson and three of the ten duly elected members of the House did not recognize secession and retained their seats in TN 2, 3 and 4.[36])

Although secessionist factions passed resolutions of secession in Missouri October 31, 1861,[42] and in Kentucky November 20, 1861,[43] their state delegations in the U.S. Congress remained in place, seven from Missouri and ten from Kentucky.[36] Exile state governments resided with Confederate armies out-of-state, army-elected congressional representatives served as a solid pro-Jefferson Davis administration voting bloc in the Confederate Congress.[44]

Party summary

Senate

| Party (shading shows control) |

Total | Vacant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (D) |

Republican (R) | Unionist (U) | Other (O) | |||

| End of the previous congress | 25 | 26 | 0 | (American) 2 |

53 | 15 |

| Begin | 22 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 52 | 16 |

| End | 12 | 30 | 7 | 49 | 19 | |

| Final voting share | 24.5% | 61.2% | 14.3% | 0.0% | ||

| Beginning of the next congress | 10 | 31 | 4 |

3 (Unconditional Unionist) |

48 | 20 |

House of Representatives

| Party (shading shows control) |

Total | Vacant | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Unionist (CU) |

Democratic (D) | Independent Democratic (ID) | Republican (R) | Unionist (U) | Other | |||

| End of the previous congress | 0 | 6 | 56 | 116 | 0 | 32 | 210 | 29 |

| Begin | 2 | 44 | 1 | 107 | 23 | 0 | 177 | 63 |

| End | 1 | 45 | 106 | 30 | 183 | 57 | ||

| Final voting share | 0.5% | 24.6% | 0.5% | 57.9% | 16.4% | 0.0% | ||

| Beginning of the next congress | 0 | 72 | 0 | 85 | 9 | 14 | 180 | 61 |

Leadership

Senate

House of Representatives

- Speaker: Galusha A. Grow (R)

Members

This list is arranged by chamber, then by state. Senators are listed in order of seniority, and Representatives are listed by district.

Senate

Senators were elected by the state legislatures every two years, with one-third beginning new six-year terms with each Congress. Preceding the names in the list below are Senate class numbers, which indicate the cycle of their election. In this Congress, Class 1 meant their term ended with this Congress, requiring reelection in 1862; Class 2 meant their term began in the last Congress, requiring reelection in 1864; and Class 3 meant their term began in this Congress, requiring reelection in 1866.

Alabama

Arkansas

California

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

|

Mississippi

Missouri

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New York

North Carolina

Ohio

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Tennessee

Texas

Vermont

Virginia

Wisconsin

|

President pro tempore Solomon Foot |

House of Representatives

The names of members of the House of Representatives are listed by their districts.

Changes in membership

The count below reflects changes from the beginning of this Congress.

Senate

| State (class) |

Vacator | Reason for change | Successor | Date of successor's formal installation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missouri (3) | Vacant | Did not take seat until after Congress commenced. | Waldo P. Johnson (D) | March 17, 1861 |

| Kansas (2) | Vacant | Election not recognized by US Senate. | James H. Lane (R) | April 4, 1861 |

| Kansas (3) | Vacant | Election not recognized by the Senate. | Samuel C. Pomeroy (R) | April 4, 1861 |

| Pennsylvania (1) | Simon Cameron (R) | Resigned March 4, 1861 to become Secretary of War. Successor was elected. |

David Wilmot (R) | March 14, 1861 |

| North Carolina (2) | Thomas Bragg (D) | Withdrew[46] March 6, 1861; expelled later in 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Ohio (3) | Salmon P. Chase (R) | Resigned March 7, 1861 to become Secretary of the Treasury. Successor was elected. |

John Sherman (R) | March 21, 1861 |

| Texas (1) | Louis T. Wigfall (D) | Withdrew March 23, 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| North Carolina (3) | Thomas L. Clingman (D) | Withdrew[46] March 28, 1861; expelled later in 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Virginia (2) | Robert M. T. Hunter (D) | Withdrew[46] March 28, 1861 and later expelled for support of the rebellion. Successor was elected. |

John S. Carlile (U) | July 9, 1861 |

| Virginia (1) | James M. Mason (D) | Expelled March 28, 1861 for supporting the rebellion. Successor was elected. |

Waitman T. Willey (U) | July 9, 1861 |

| Illinois (2) | Stephen A. Douglas (D) | Died June 3, 1861. Successor was appointed. |

Orville H. Browning (R) | June 26, 1861 |

| Texas (2) | John Hemphill (D) | Expelled sometime in July 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Illinois (2) | Orville H. Browning (R) | Interim appointee lost election to finish the term. Successor elected January 12, 1863. |

William A. Richardson (D) | January 30, 1863 |

| Arkansas (2) | William K. Sebastian (D) | Expelled July 11, 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Arkansas (3) | Charles B. Mitchel (D) | Expelled July 11, 1861. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Michigan (2) | Kinsley S. Bingham (R) | Died October 5, 1861. Successor was elected. |

Jacob M. Howard (R) | January 17, 1862 |

| Oregon (2) | Edward D. Baker (R) | Killed at Battle of Ball's Bluff October 21, 1861. Successor was appointed. |

Benjamin Stark (D) | October 29, 1861 |

| Kentucky (3) | John C. Breckinridge (D) | Expelled December 4, 1861 for supporting the rebellion. Successor was elected. |

Garrett Davis (U) | December 23, 1861 |

| Missouri (1) | Trusten Polk (D) | Expelled January 10, 1862 for supporting the rebellion. Successor was appointed. |

John B. Henderson (U) | January 17, 1862 |

| Missouri (3) | Waldo P. Johnson (D) | Expelled January 10, 1862 for disloyalty to the government. Successor was appointed. |

Robert Wilson (U) | January 17, 1862 |

| Indiana (1) | Jesse D. Bright (D) | Expelled February 5, 1862 on charges of disloyalty. Successor was appointed. |

Joseph A. Wright (U) | February 24, 1862 |

| Tennessee (1) | Andrew Johnson (D) | Resigned March 4, 1862. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Rhode Island (1) | James F. Simmons (R) | Resigned August 15, 1862. Successor was elected. |

Samuel G. Arnold (R) | December 1, 1862 |

| New Jersey (1) | John R. Thomson (D) | Died September 12, 1862. Successor was appointed. |

Richard S. Field (R) | November 21, 1862 |

| Oregon (2) | Benjamin Stark (D) | Retired September 12, 1862 upon election of a successor. | Benjamin F. Harding (D) | September 12, 1862 |

| Maryland (3) | James Pearce (D) | Died December 20, 1862. Successor was appointed. |

Thomas H. Hicks (U) | December 29, 1862 |

| Indiana (1) | Joseph A. Wright (U) | Retired January 14, 1863 upon election of a successor. | David Turpie (D) | January 14, 1863 |

| New Jersey (1) | Richard S. Field (R) | Retired January 14, 1863 upon election of a successor. | James W. Wall (D) | January 14, 1863 |

House of Representatives

| District | Vacator | Reason for change | Successor | Date successor seated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorado Territory At-large | New seat. | Hiram P. Bennett (Conservative R) | August 19, 1861 | |

| Nevada Territory At-large | New seat. | John Cradlebaugh (I) | December 2, 1861 | |

| Dakota Territory At-large | New seat. | John B. S. Todd (D) | December 9, 1861 | |

| Louisiana 1st | Vacant. | Benjamin F. Flanders (U) | December 3, 1862 | |

| Louisiana 2nd | Vacant. | Michael Hahn (U) | December 3, 1862 | |

| Tennessee 3rd | Vacant | Representative-elect George W. Bridges was arrested by Confederate troops while en route to Washington, D.C. and held prisoner before he escaped. | George W. Bridges (U) | February 25, 1863 |

| Virginia 1st | Vacant. | Joseph E. Segar (U) | May 6, 1862[45] | |

| California At-large | Vacant | Low not permitted to take seat, qualified later under special act of Congress. | Frederick F. Low (R) | June 3, 1862 |

| Virginia 7th | Vacant. | Charles H. Upton (U) | July 4, 1861[45] | |

| Ohio 7th | Thomas Corwin (R) | Resigned March 12, 1861 to become Minister to Mexico. | Richard A. Harrison (U) | July 4, 1861 |

| Ohio 13th | John Sherman (R) | Resigned March 12, 1861 when elected U.S. Senator. | Samuel T. Worcester (R) | July 4, 1861 |

| Pennsylvania 12th | George W. Scranton (R) | Died March 24, 1861. | Hendrick B. Wright (D) | July 4, 1861 |

| Massachusetts 3rd | Charles F. Adams, Sr. (R) | Resigned May 1, 1861 to become Ambassador to Great Britain. | Benjamin Thomas (U) | June 11, 1861 |

| Pennsylvania 2nd | Edward Joy Morris (R) | Resigned June 8, 1861 to become Minister Resident to Turkey. | Charles J. Biddle (D) | July 2, 1861 |

| Virginia 11th | John S. Carlile (U) | Resigned July 9, 1861 to become United States Senator from the loyal faction of Virginia. | Jacob B. Blair (U) | December 2, 1861 |

| Missouri 3rd | John B. Clark (D) | Expelled July 13, 1861 for having taken up arms against the Union. | William A. Hall (D) | January 20, 1862 |

| Oregon At-large | Andrew J. Thayer (D) | Election was successfully contested July 30, 1861. | George K. Shiel (D) | July 30, 1861 |

| Missouri 5th | John W. Reid (D) | Withdrew August 3, 1861 and then expelled December 2, 1861 for having taken up arms against the Union. | Thomas L. Price (D) | January 21, 1862 |

| Iowa 1st | Samuel Curtis (R) | Resigned August 4, 1861 to become colonel of the 2nd Iowa Infantry. | James F. Wilson (R) | October 8, 1861 |

| Massachusetts 5th | William Appleton (CU) | Resigned September 27, 1861 due to failing health. | Samuel Hooper (R) | December 2, 1861 |

| Illinois 6th | John A. McClernand (D) | Resigned October 28, 1861 to accept a commission as brigadier general of volunteers for service in the Civil War. | Anthony L. Knapp (D) | December 12, 1861 |

| Kentucky 1st | Henry C. Burnett (D) | Expelled December 3, 1861 for support of secession. | Samuel L. Casey (U) | March 10, 1862 |

| Kentucky 2nd | James S. Jackson (U) | Resigned December 13, 1861 to enter the Union Army. | George H. Yeaman (U) | December 1, 1862 |

| Virginia 7th | Charles H. Upton (U) | Declared not entitled to seat February 27, 1862. | Lewis McKenzie (U) | February 16, 1863 |

| Illinois 9th | John A. Logan (D) | Resigned April 2, 1862 to enter the Union Army. | William J. Allen (D) | June 2, 1862 |

| Pennsylvania 7th | Thomas B. Cooper (D) | Died April 4, 1862. | John D. Stiles (D) | June 3, 1862 |

| Massachusetts 9th | Goldsmith F. Bailey (R) | Died May 8, 1862. | Amasa Walker (R) | December 1, 1862 |

| Maine 2nd | Charles W. Walton (R) | Resigned May 26, 1862 to become associate justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. | Thomas A. D. Fessenden (R) | December 1, 1862 |

| Missouri 1st | Francis P. Blair, Jr. (R) | Resigned July 1862 to become colonel in Union Army. | Vacant thereafter | |

| Wisconsin 2nd | Luther Hanchett (R) | Died November 24, 1862. | Walter D. McIndoe (R) | January 26, 1863 |

| Illinois 5th | William A. Richardson (D) | Resigned January 29, 1863 after being elected to the U.S. Senate. | Vacant thereafter | |

Committees

Senate

Standing committees of the Senate resolved, Friday, March 8, 1861[47]

Foreign Relations

Finance

Commerce

Military Affairs and Militia

Naval Affairs

Judiciary

Post Offices and Post Roads

Public Lands

Private Land Claims

Indian Affairs

|

Pensions

Revolutionary Claims

Claims

District of Columbia

Patents and Patent Office

Public Buildings and Grounds

Territories

Audit and Control the Contingent Expenses of the Senate

Printing

Engrossed Bills

Enrolled Bills

The Library

Order in the Galleries (Select)

|

House of Representatives

Members by committee assignments, Congressional Globe, as published July 8, 1861[48] Spellings conform to those found in the Congressional Biographical Dictionary.

Unless otherwise noted, all committees listed are Standing, as found at the Library of Congress[49]

Accounts

Agriculture

Claims

Commerce

Confiscation of Rebel Property (Select)

District of Columbia

Elections

Emancipation

Expenditures in the State Department

Expenditures in the Treasury Department

Expenditures in the War Department

Expenditures in the Post Office Department

Expenditures in the Interior Department

Finance

Foreign Affairs

|

Indian Affairs

Invalid Pensions

Judiciary

Lake and River Defences

Manufactures

Mileage

Military Affairs

Military Railroad

Militia

Naval Affairs

Niagara Ship Canal (Select)

Pacific Railroad

Patents

Pensions

Post Offices and Post Roads

|

Printing

Private Land Claims

Public Lands

Public Buildings and Grounds

Public Expenditures

Revised and Unfinished Business

Revolutionary Claims

Revolutionary Pensions

Roads and Canals

State of the Union

Territories

Ways and Means

|

Joint committees

Enrolled Bills

- Bradley F. Granger (R-Michigan)

- George T. Cobb (D-New Jersey)

Library

- Edward McPherson (R-Pennsylvania)

- Augustus Frank (R-New York)

- John Law (D-Indiana)

Employees

Senate

- Chaplain: Phineas D. Gurley (Presbyterian)

- Byron Sunderland (Presbyterian), elected July 10, 1861

- Secretary: Asbury Dickens[52]

- John W. Forney, elected July 15, 1861

- William Hickey (Chief Clerk) apptd "Acting Sec'y", March 22, 1861[53]

- Sergeant at Arms: Dunning R. McNair

- George T. Brown, elected July 6, 1861

House of Representatives

- Chaplain of the House: Thomas H. Stockton (Methodist)

- Clerk: John W. Forney

- Emerson Etheridge, elected July 4, 1861

- Doorkeeper: Ira Goodnow

- Messenger to the Speaker: Thaddeus Morrice

- Postmaster: William S. King

- Sergeant at Arms: Henry William Hoffman

- Edward Ball, elected July 5, 1861

See also

- United States elections, 1860 (elections leading to this Congress)

- United States elections, 1862 (elections during this Congress, leading to the next Congress)

References

- ↑ Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress (1774-2005) found online at Congress Profiles: 37th Congress (1861-1863) viewed October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Martis, Kenneth C. 1989. p. 115

- ↑ Martis, Kenneth C. "The historical atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America: 1861-1865" 1994 ISBN 0-13-389115-1, p. 32.

- ↑ Heidler, D.S.; Heidler, J.T.; Coles, D.J. (2000). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. p. 441. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- ↑ "The White House Historical Association, "The Great Cause of Union" search on 'habeas corpus'".

- ↑ "Ordinance of Secession of Arkansas". Csawardept.com. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Ordinance of Secession of North Carolina". Csawardept.com. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Ordinance of Secession of Virginia". Csawardept.com. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Martis, Kenneth C.; et al. (1989). The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789-1989. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-920170-5.

- ↑ "Ordinance of Secession of Tennessee". Csawardept.com. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ Martis, Kenneth C., p. 115, 117.

- ↑ Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress (1774-2005) found online at Congress Profiles: 37th Congress (1861-1863) viewed October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas

- ↑ Excerpt from Isaac Bassett's Memoir re-published on the U.S. Senate webpage

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (2008). Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. The Penguin Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-59420-191-2.

- ↑ Neely, Mark E., Jr., "Chapter 12. The Civil War" in "The American Congress: the building of a democracy", Julian E. Zelizer, ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 2004, ISBN 0-618-17906-2, p. 208

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 37 Cong. 1 sess. p. 233

- 1 2 3 4 Neely, p. 210

- ↑ Martis, p.115

- ↑ "Presidential Proclamation May 19, 1862", Abraham Lincoln's response to General Hunter's General Order Number Eleven. abolition was to be outside the police functions of field commanders.

- ↑ New York Times: "How Slavery Really Ended in America" Viewed November 9, 2011.

- 1 2 McPherson, p. 57-58

- 1 2 Neely, p. 214

- ↑ McPherson, p. 142

- ↑ www

.archives .gov /exhibits /featured _documents /emancipation _proclamation /transcript .html - ↑ Blaine, James G. "Memoir re-published on the National Archives webpage".

- 1 2 Neely, p. 212-213

- ↑ McPherson, p. 76

- 1 2 Neely, p. 211

- ↑ Neely, p. 213

- ↑ Erickson, Stephen C. (Winter 1995). "The Entrenching of Incumbency: Reelections in the U.S. House of Representatives, 1790-1994". The Cato Journal.

- ↑ Swain, John W., et al., "A New Look at Turnover in the U.S. House of Representatives, 1789-1998", American Politics Research 2000, (28:435), p. 444, 452.

- ↑ Straus, William and Howe, Neil, Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584-2069 William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1991, ISBN 0-688-08133-9, 196

- ↑ Straus, p.462

- ↑ Straus, 182

- 1 2 3 4 Martis, Kenneth C., "The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress: 1789-1989" ISBN 0-02-920170-5. p. 114.

- ↑ The text of Virginia's Ordinance of Secession.

- ↑ The text of Arkansas's Ordinance of Secession.

- ↑ The text of North Carolina's Ordinance of Secession.

- ↑ The text of Tennessee's Ordinance of Secession.

- ↑ The Tennessee legislature ratified an agreement to enter a military league with the Confederate States on May 7, 1861. Tennessee voters approved the agreement on June 8, 1861.

- ↑ Missouri Ordinance of Secession

- ↑ Kentucky Ordinance of Secession

- ↑ Martis, Kenneth C., "The historical atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America: 1861-1865", ISBN 0-13-389115-1, p.92-93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress, (1774–2005), "Official Annotated Membership Roster by State with Vacancy and Special Election Information for the 37th Congress".

- 1 2 3 Withdrawal" meant that these senators announced they were withdrawing from the Senate due to their states' decisions to secede from the Union. Their seats were later declared vacant by the Senate, but some seats were actually unfilled since the beginning of this Congress on March 4, 1861.

- ↑ "Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, 1789-1873". p. 412.

- ↑ "Congressional Globe". July 8, 1861. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 37th Congress, Browse by Committee".

- 1 2 The Bibliography of Vermont, Gilman, M.D.,The Free Press Association, 1897. p. 320.

- ↑ Lanman, Charles (1887). Biographical annals of the civil government of the United States. New York: JM Morrison. p. 514.

- ↑ "US Senate Art & History webpage, "Ashbury Dickens, Secretary of the Senate, 1836-1861"".

- ↑ "Congressional Biographical Dictionary, 37th Congress" (PDF). p. 162, footnote fn 2.

- Martis, Kenneth C. (1982). The Historical Atlas of United States Congressional Districts. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

External links

- Statutes at Large, 1789-1875

- Senate Journal, First Forty-three Sessions of Congress

- House Journal, First Forty-three Sessions of Congress

- Congressional Directory for the 37th Congress, 2nd Session.

- Congressional Directory for the 37th Congress, 3rd Session.