Siege of Fort St. Jean

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

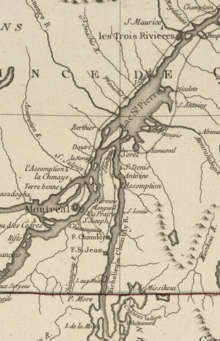

The Siege of Fort St. Jean (also called St. John, St. Johns, or St. John's) was conducted by American Brigadier General Richard Montgomery on the town and fort of Saint-Jean in the British province of Quebec during the American Revolutionary War. The siege lasted from September 17 to November 3, 1775.

After several false starts in early September, the Continental Army established a siege around Fort St. Jean. Beset by illness, bad weather, and logistical problems, they established mortar batteries that were able to penetrate into the interior the fort, but the defenders, who were well-supplied with munitions, but not food and other supplies, persisted in their defence, believing the siege would be broken by forces from Montreal under General Guy Carleton. On October 18, the nearby Fort Chambly fell, and on October 30, an attempt at relief by Carleton was thwarted. When word of this made its way to St. Jean's defenders, combined with a new battery opening fire on the fort, the fort's defenders capitulated, surrendering on November 3.

The fall of Fort St. Jean opened the way for the American army to march on Montreal, which fell without battle on November 13. General Carleton escaped from Montreal, and made his way to Quebec City to prepare its defences against an anticipated attack.

Background

Fort Saint-Jean guarded the entry to the province of Quebec on the Richelieu River at the northern end of Lake Champlain. When Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga and raided Fort St. Jean in May 1775, Quebec was garrisoned by about 600 regular troops, some of which were widely distributed throughout Quebec's large territory.[7]

Continental Army preparations

The invasion of Quebec began when about 1500 men, then under the command of General Philip Schuyler, arrived at the undefended Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River on September 4, 1775. On September 6, the Americans began making forays toward Fort St. Jean, only 10 mi (16 km) away.[8] The army was initially composed of militia forces from New York and Connecticut, with most of its operation directed by Brigadier General Richard Montgomery, who took over complete command from Schuyler on September 16, when Schuyler became too ill to continue leading the invasion.[9][10]

British defensive preparations

Fort St. Jean had been under preparations for an attack from the south ever since Arnold's raid on Fort St. Jean on May 18, in which he captured its small garrison and Lake Champlain's only large military ship. When news of that raid reached Montreal, 140 men under the command of Major Charles Preston were immediately dispatched to hold the fort. Another 50 Canadian militia were raised in Montreal on May 19, and were also sent to the fort.[11]

When Moses Hazen, the messenger bearing news of Arnold's raid, reached Quebec City and notified British Governor and General Guy Carleton of the raid, Carleton immediately dispatched additional troops from there and Trois-Rivières to St. Jean. Carleton himself went to Montreal on May 26 to oversee arrangements for the defense of the province, which he decided to concentrate on St. Jean, as it was the most likely invasion route.[12][13]

By the time the Americans arrived at Île-aux-Noix, Fort St. Jean was defended by about 750 men under the command of Major Charles Preston. The majority of these were regular troops from the 7th and 26th Regiments of Foot and the Royal Artillery. There were 90 locally-raised militia, and 20 members of Colonel Allen Maclean's Royal Highland Emigrants, men who were veterans of the French and Indian War. A detachment of Indians (probably Caughnawaga from a nearby village) patrolled outside the fort under the direction of Claude de Lorimier and Gilbert Tice. The Richelieu River was patrolled by an armed schooner, Royal Savage, under the command of Lieutenant William Hunter, with other boats under construction.[14]

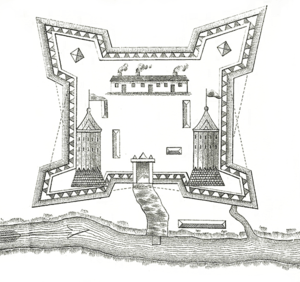

The fort itself, sited on the west bank of the Richelieu River, consisted of two earthen redoubts about 600 feet (180 m) apart, surrounded by a ditch 7 feet (2.1 m) wide and 8 feet (2.4 m) deep that was lined with chevaux de frise. The southern redoubt was roughly 250 by 200 feet (80 by 65 metres), and it contained 6 buildings, including a bake house, the fort's magazine, and storage houses. The northern redoubt was slightly larger, enclosing a two-storey stone house that was used as a barracks. The defenders had cleared brush for several hundred yards around the fort to ensure a clear field of fire. They had put up a wooden palisade to the west of the redoubts, and dug a trench connecting the two redoubts, for ease of communications. The eastern side of the fort faced the river, where there was a shipyard and anchorage for Royal Savage.[15]

First approach

Skirmish with Indians

On September 6, Generals Schuyler and Montgomery led a force of men in bateaux to a landing point about 1 mile (1.6 km) upriver from Fort St. Jean. Schuyler remained with the boats while Montgomery led some men into the swampy lands above the fort. There they were surprised by about 100 Indians led by Tice and Lorimier.[16] In the ensuing skirmish, the Americans suffered 8 dead and 9 wounded, while the Indians suffered 4 dead and 5 wounded, with Tice among the wounded.[17] The American troops, which were relatively untried militia forces, retreated to the boats, where they erected a breastwork for protection. The fort's defenders, seeing this, fired their cannon at the breastwork, prompting the Americans to retreat about 1 mile (1.6 km) upriver, where they set up a second breastwork and camped for the night. The Indians, resentful that neither the British forces in the fort nor the habitants had come to their support in the engagement, returned to their homes.[16][17]

At this camp, Schuyler was visited by a local man, believed by some historians to be Moses Hazen.[18] Hazen, a Massachusetts-born retired officer who lived near the fort, painted a bleak portrait of the American situation. He said that the fort was defended by the entire 26th regiment and 100 Indians, that it was well-stocked and ready for a siege. He also said that the habitants, while friendly to the American cause, were unlikely to help the Americans unless the prospects for victory looked good. Schuyler held a war council on September 7, in which the command decided to retreat back to Île-aux-Noix.[19] However, on September 8, reinforcements arrived: another 800 men including Connecticut militia under David Wooster and New Yorkers with artillery, joined them.[20] Heartened by this arrival, they decided instead to proceed with a nighttime attempt on the fort. Schuyler, whose illness was getting more severe (he was so ill "as not to be able to hold the pen"), turned command of the army over to Montgomery.[21]

Reports of this first contact between opposing forces outside St. Jean were often wildly exaggerated, with many local reports claiming it as some kind of victory. The Quebec Gazette, for example, reported that 60 Indians had driven off 1,500 Americans, killing 30 and wounding 40.[22] Following this news, General Carleton issued orders for all of the nearby parishes to call up ten percent of their militia. Officers of the militia reported to Montreal, but many militia men stayed home. By September 7, a troop of about 120 men was raised, which was sent to Fort St. Jean.[23]

Propaganda and recruiting

On September 8, Schuyler sent Ethan Allen (acting as a volunteer since he had been deposed as head of the Green Mountain Boys by Seth Warner) and John Brown to circulate a proclamation announcing the Americans' arrival, and their desire to free the Canadians from the bondage of British rule. Allen and Brown traveled through the parishes between St. Jean and Montreal, where they were well-received, and even provided with local guards. James Livingston, a local grain merchant (and a relative of Montgomery's wife), began raising a local militia near Chambly, eventually gathering nearly 300 men.[24]

Allen also visited the village of the Caughnawaga, from whom he received assurances of their neutrality.[24] The Caughnawaga had been the subject of a propaganda war, with Guy Johnson, the British Indian agent, trying to convince them (as well as other tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy) to take up arms against the Americans. However, Schuyler had successfully negotiated an agreement in August with most of the Iroquois to remain neutral. Word of this agreement reached the Caughnawaga on September 10; when Carleton and Johnson learned of it, Johnson sent Daniel Claus and Joseph Brant in an attempt to change the minds of the Caughnawaga; their entreaties were refused.[25]

Second approach

On the night of September 10, Montgomery led 1000 men out again, returning to the first landing site by boat. In the confusion of the darkness and the swamp, some of the troops were separated from the rest. When they encountered one another again, there was panic, as the each mistook the other for the enemy. After just 30 minutes in the swamp, they returned to the landing.[26] Montgomery, who had stayed with the boats, sent the troops out again. This time, the vanguard encountered a few Indians and habitants, and again panicked. Two of the "enemy" were killed, but the troops again made a disorderly retreat to the landing, which their commander, Colonel Rudolphus Ritzema, was apparently unable to stop.[27]

While the command staff met to discuss the next move, word came in that the British warship Royal Savage was approaching. This started a disorganized retreat up the river back to Ile-aux-Noix, in which the command staff was nearly left behind.[27]

A third attempt was planned for September 13; bad weather delayed attempts until September 16. However, General Schuyler was by this time so ill that he thought it necessary to withdraw to Ticonderoga. He left that day, turning full command of the invasion over to Montgomery. Schuyler was not the only one falling ill; the bad weather, and the swampy, malaria-infested terrain of Île-aux-Noix was also taking a toll on the troops, as more of them became ill as well.[28] The bad news was tempered by good; an additional 250 troops, in the form of a company of Green Mountain Boys under Seth Warner, and another company of New Hampshire men under Colonel Timothy Bedel, arrived at Île-aux-Noix.[29]

Siege begins

On September 17, Montgomery's army disembarked from their makeshift fleet just south of St. Jean, and sent out John Brown with a detachment to block the road going north from the fort to Montreal. A small flotilla of armed boats guarded the river against the possibility of Royal Savage attacking the army as it landed.[29]

Brown and his men made their first interdiction that day, capturing a wagon-train of supplies destined for the fort. Preston, seeing that this had happened, sent out a sortie to recover the goods. Brown's men, who had had time to hide the supplies in the woods, retreated until the sounds of the conflict reached the main body of the army. Montgomery, along with Bedel and his company, rushed to Brown's aid, and succeeded in driving the British back into the fort without recovering the supplies.[30] During this encounter, Moses Hazen was first captured and questioned by Brown, and then arrested again by the British, and brought into the fort. That night, Hazen and Lorimier, the Indian agent, sneaked out of the fort and went to Montreal, to report the situation to Carleton.[10]

Montgomery began entrenching his troops around the fort on September 18, and constructing a mortar battery south of the fort.[31] He ordered Brown to establish a position at La Prairie, one of the sites where there was a crossing of the Saint Lawrence River to Montreal. Ethan Allen went with a small company of Americans to collect Canadiens that Livingston had been recruiting, and take them to monitor Longueuil, the other major crossing point. Livingston had established a base at Point-Olivier, below Fort Chambly, another aging fort at the base of some rapids in the Richelieu River, and was urging his compatriots to join him there. Some Loyalists attempted to dissuade others from joining with Livingston; Livingston's supporters sometimes violently opposed attempts by Loyalists to organize, and Carleton did nothing at the time to assist the Loyalists outside the city.[32]

Allen, who was already renowned for his bravado in the action at Fort Ticonderoga, decided, when he reached Longueuil on September 24, to attempt the capture of Montreal. In the Battle of Longue-Pointe, this effort failed on the next day, with Allen and a number of men captured by the British.[33] The alarm raised by Allen's proximity to Montreal resulted in the mustering of about 1,200 men from rural districts outside Montreal. Carleton failed to capitalize on this upwelling of Loyalist support by using them for a relief expedition against the besieging Americans. After several weeks of inaction by Carleton, the rural men drifted away, called by the demands of home and harvest. (Carleton did take advantage of the moment to order the arrest of Thomas Walker, a Montreal merchant who was openly pro-American and had been reporting to the Americans.)[34]

The conditions for the Americans constructing the siege works were difficult. The ground was swampy, and the trenches quickly became filled knee-deep in water. Montgomery described his army as "half-drowned rats crawling through a swamp".[35] To make matters even worse, food and ammunition supplies were running out, and the British showed no sign of giving in despite the American bombardment.[35] Disease also worked to reduce the effectiveness of the Americans; by mid-October, more than 900 men had been sent back to Ticonderoga due to illness.[36] In the early days of the siege, the fort's defenders took advantage of the land they had cleared around the fort to make life as difficult as possible for the besiegers erecting batteries. Major Preston wrote in his journal on September 23 that "a deserter [tells us where] the enemy are erecting their battery and we distress them as much as we can with shells."[37] Until large guns arrived from Ticonderoga, the fort's defenders enjoyed a significant advantage in firepower.[37]

Large cannon arrive

On October 6, a cannon that was dubbed the "Old Sow" arrived from Ticonderoga. Put in position the next day, it started lobbing shells at the fort. Montgomery then began planning the placement of a second battery. While he first wanted to place one to the northwest of the fort, his staff convinced him instead to place on the eastern shore of the Richelieu, where it would command the shipyard and Royal Savage.[38] This battery, whose construction was complicated by an armed row galley sent from the fort to oppose the works, was completed on October 13, and opened fire the next day. One day after that, Royal Savage lay in ruins before the fort. Its commander had, in anticipation of her destruction, ordered her to be anchored where her supplies and armaments might be recovered.[39]

Fort Chambly taken

James Livingston had advanced to Montgomery the idea of taking Fort Chambly, near where his militia was encamped. One of Livingston's captains, Jeremy Duggan, had, on September 13, floated two nine-pound guns past St. Jean, and these guns were put to use to that end. Chambly, which was garrisoned by only 82 men, mostly from the 7th Foot, was surrendered on October 18 by its commander, Major Joseph Stopford, after two days of bombardment. Most seriously, Stopford failed to destroy supplies that were vitally useful to the Americans, primarily gunpowder, but also winter provisions.[40] Six tons of powder, 6,500 musket cartridges, 125 muskets, 80 barrels of flour and 272 barrels of foodstuff were captured.[35]

Timothy Bedel negotiated a cease-fire with Major Preston so that the prisoners captured at Chambly could be floated up the river past St. Jean.[41] The loss of Chambly had a dispiriting effect at St. Jean; some of the militia wanted to surrender, but Preston would not allow it.[42] Following Chambly's capitulation, Montgomery renewed his intention to construct a battery northwest of St. Jean. This time, his staff raised no objections, and by the end of October guns that were emplaced there opened fire on the fort.[43]

Carleton tries to help

In Montreal, Carleton was finally prodded to move. Under constant criticism for failure to act sooner, and mistrustful of his militia forces, he developed a plan of attack. He sent word to Colonel Allan Maclean at Quebec to bring more of his Royal Highland Emigrants and some militia forces to Sorel, from where they would move up the Richelieu toward St. Jean, while Carleton would lead a force across the Saint Lawrence at Longueuil.[44]

Maclean raised a force of about 180 Emigrants, and a number of militia. By the time he reached Sorel on October 14, he had raised, in addition to the Emigrants, about 400 militia men, sometimes using threatening tactics to gain recruits.[45] His and Carleton's hopes were dashed on October 30, when Carleton's attempted landing at Longueuil of a force numbering about 1,000 (mostly militia, with some Emigrants and Indian support) was repulsed by the Americans. A few of his boats were landed, but most were driven off by Seth Warner's use of field artillery that had been captured at Chambly.[46]

Maclean attempted to press forward, but his militia forces began to desert him, and the forces under Brown and Livingston were growing in number. He retreated back to Sorel, and made his way back to Quebec.[47]

Surrender

In late October, the American troop strength surged again with the arrival of 500 men from New York and Connecticut, including Brigadier General David Wooster.[43] This news, combined with the new battery trained on the fort, news of the failed relief expedition, and dwindling supplies, made the situation in the fort quite grim.[47]

On November 1, Montgomery sent a truce flag, carried by a prisoner captured during Carleton's aborted relief attempt, into the fort. The man delivered a letter, in which Montgomery, pointing out that relief was unlikely to come, offered to negotiate a surrender.[48] Preston, not entirely trusting the man's report, sent out one of his captains to confer with Montgomery. The counteroffer, which Montgomery rejected, owing to the lateness of the season, was to hold a truce for four days, after which the garrison would surrender if no relief came. Montgomery let the captain examine another prisoner from Carleton's expedition, who confirmed what the first one had reported. Montgomery then repeated his demand for an immediate surrender, terms for which were drawn up the next day.[49]

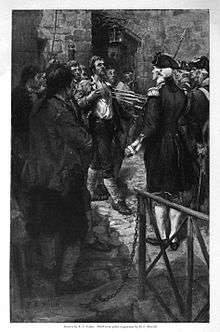

Preston's troops marched out of the fort and surrendered their weapons on November 3, with the regulars in full dress uniform.[50] He surrendered 536 officers and soldiers, 79 Canadien and 8 English volunteers.[51]

Aftermath

Following the news of St. Jean's surrender, Carleton immediately began preparing to leave Montreal. He left Montreal on November 11, two days before American troops entered the city without opposition. Narrowly escaping capture when his fleet was forced to surrender after being threatened by batteries at Sorel, he made his way to Quebec to prepare that city's defenses.[52]

Casualties on both sides during the siege were relatively light, but the Continental Army suffered a significant reduction in force due to illness throughout the siege.[36] Furthermore, the long siege meant that the Continental Army had to move on Quebec City with winter setting in, and with many enlistments nearing expiration at year's end.[53] Richard Montgomery was promoted to Major General on December 9, 1775, as a result of his successful capture of Saint Jean and Montreal. He never found out; the news did not reach the American camp outside Quebec before he died in the December 31 Battle of Quebec.[54]

In 1776, the British reoccupied the fort following the Continental Army's abandonment of it during its retreat to Fort Ticonderoga.[55]

Legacy

The British (and then Canadian) military occupied the Fort Saint-Jean site until 1995, using it since 1952 as the campus of the Royal Military College, which still occupies part of the site. The site now includes a museum devoted to the 350-year military history of Fort Saint-Jean.[56]

Siege of Fort St. Jean is mentioned in a Fort Saint-Jean plaque erected in 1926 by Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada at the Royal Military College Saint-Jean. "Constructed in 1743 by M. de Léry under orders from Governor la Galissonnière. This post was for all the military expeditions towards Lake Champlain. In August 31, 1760, Commandant de Roquemaure had it blown up in accordance with orders from the Governor de Vaudreuil in order to prevent its falling into the hands of the English. Rebuilt by Governor Carleton, in 1773. During the same year, under the command of Major Charles Preston of the 26th Regiment, it withstood a 45 day siege by the American troops commanded by General Montgomery."

Sources

- ↑ The number of American forces in this action were highly variable, due to the arrival of additional troops, and the departure of the sick and wounded, during the action. Likewise, the exact number of troops involved in the capture of Chambly, which were a subset of the American forces and Canadian militia, are difficult to count accurately. Stanley, p. 55 estimates that there 200-500 troops besieging Chambly. While the initial invasion force was about 1500 (Stanley, p. 37), any other firm counts are unreliable. Stanley, p. 60, lists the British estimates of the American force at 2000 prior to St. Jean's surrender.

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 33–34 lists 662 regulars and militia, and about 100 Indians. Wood, p. 37 lists 725 total.

- ↑ Stanley, p. 54

- ↑ As with the American troop strengths, determining the exact number of casualties is difficult, in part because different sources may count casualties attached to a particular action differently. Zuehlke, p. 51, and Stanley, p. 62, estimate American casualties at 100, while Smith, p. 458, says there were only 20. Gabriel, p. 112 cites 900 sick removed to Ticonderoga by mid-October.

- 1 2 Stanley, p. 62

- ↑ Lanctot p. 92 lists the surrender count at St. Jean, to which the Chambly garrison size is added

- ↑ Stanley, p. 29

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 37–39

- ↑ Bird, p. 56

- 1 2 Stanley, p. 41

- ↑ Lanctot, p. 44

- ↑ Lanctot, pp. 50,53

- ↑ Smith, p. 342

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Gabriel, p. 106

- 1 2 Gabriel, p. 98

- 1 2 Stanley, p. 39

- ↑ Gabriel, Stanley, Morrissey, and Smith all make this claim. Stanley cites Smith, p. 612, as providing a reliable conclusion that the man was Hazen.

- ↑ Gabriel, p. 99

- ↑ Bird, p. 89

- ↑ Gabriel, p. 100

- ↑ Smith, p. 330

- ↑ Lanctot, p. 64

- 1 2 Lanctot, p. 65

- ↑ Smith, pp. 357–359

- ↑ Gabriel, pp. 100–101

- 1 2 Gabriel, p. 101

- ↑ Smith, p. 335

- 1 2 Bird, p. 93

- ↑ Bird, pp. 94–95

- ↑ Bird, p. 96

- ↑ Stanley, p. 42

- ↑ Lanctot, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 48–49

- 1 2 3 Wood, p. 39

- 1 2 Gabriel, p. 112

- 1 2 Stanley, p. 51

- ↑ Gabriel, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Gabriel, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Stanley, p. 55

- ↑ Gabriel, p. 121

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 56–57

- 1 2 Gabriel, p. 123

- ↑ Stanley, p. 58

- ↑ Smith, pp. 450–451

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 58–59

- 1 2 Stanley, p. 60

- ↑ Smith, p. 459

- ↑ Smith, p. 460

- ↑ Smith, pp. 460–465

- ↑ Lanctot, p. 91

- ↑ Bird, pp. 142–144

- ↑ Stanley, p. 65

- ↑ Bird, p. 220

- ↑ Stanley, p. 132

- ↑ Musée Fort St-Jean

References

- Anderson, Mark (2013). The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America's War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776. University Press of New England. OCLC 840463253.

- Bird, Harrison (1968). Attack on Quebec, the American Invasion of Canada, 1775. Oxford University Press. OCLC 440055.

- Gabriel, Michael (2002). Major General Richard Montgomery. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3931-3.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1967). Canada and the American Revolution 1774–1783. Harvard University Press. OCLC 70781264.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2003). Quebec 1775, The American Invasion of Canada. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-681-2.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony, vol 1. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236.

- Stanley, George (1973). Canada Invaded 1775-1776. Hakkert. ISBN 978-0-88866-578-2.

- Wood, W. J. (1990). Battles of the Revolutionary War. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81329-0.

- Zuehlke, Mark; Daniel, C. Stuart (2006). Canadian Military Atlas: Four Centuries of Conflict from New France to Kosovo. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-209-0.

- "Musée Fort St-Jean website". Fort Saint-Jean Museum. Archived from the original on April 27, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

External links

- Musée Fort St-Jean virtual exhibition (most Flash, and in French)

- Town of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

- Parks Canada - Fort Chambly National Historic Site

- Fort Chambly at Historic Lakes

- RMC History of Fort Saint Jean

.jpg)