Colin Raston

| Colin Llewellyn Raston AO | |

|---|---|

| Education | BSc(Hons), PhD, DSc[1] |

| Alma mater |

University of Western Australia Griffith University[1] |

| Occupation | academic |

| Known for | green, macrocyclic, and organometallic chemistry |

| Title |

Professor of Chemistry, Griffith University (1988–1994) Profesor of Chemistry, Monash University (1995–2000) Professor of Chemistry, The University of Leeds (2001–2002) Profesor of Chemistry, The University of Western Australia (2003–2012) Professor of Clean Technology, Flinders University (2013– )[1] |

| Awards |

Burrows Award, 1994[2] H G Smith Memorial Medal, 1996[1] Green Chemistry Challenge Award, 2002[2] Leighton Memorial Medal, 2006[2] RACI Living Luminary, 2011[2] South Australia Premier's Professorial Research Fellow in Clean Technology, 2013[1] Ig Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 2015[3] Officer of the Order of Australia, 2016[4] |

Colin Llewellyn Raston AO is a Professor of Chemistry of Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia and the Premier's Professorial Fellow in Clean Technology.[1] In 2015, he was awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in "for inventing a chemical recipe to partially un-boil an egg."[3] In 2016, Raston was made an Officer of the Order of Australia for his services to science.[4]

Research work

Early career

Raston undertook his early tertiary studies at the University of Western Australia, taking a bachelor degree in science with honours and a doctor of philosophy under Professor Allan White.[1] Raston's work included looking at marine organoarsenic compounds, isolating arsenobetaine from the Western Rock Lobster and determining its structure and synthesis.[5] This zwitterionic substance turns out to be the main source of arsenic in fish[6] and unlike other arsenic compounds (like dimethylarsine and trimethylarsine) it has comparatively low toxicity.[7] Arsenobetaine is an analog of betaine (trimethylglycine) and with similar biosynthesis to choline and betaines.[8]

He later received a higher doctorate (Doctor of Science) from Griffith University.[1]

Calixarenes

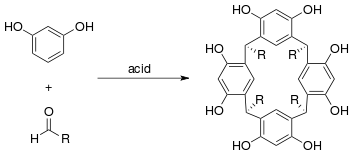

Resorcinarene is a macrocycle typically prepared by the condensation of resorcinol and formaldehyde in an acidic environment. Multiple isomers are possible when any other aldehyde is used and different conditions, including Lewis acid catalysis have been employed to minimise by-products.[9][10] Raston and co-workers have developed an alternative green chemistry solvent-free approach whereby resorcinol and the aldehyde are ground together with p-toluenesulfonic acid in a mortar and pestle and the product recrystallised from the resulting paste.[11]

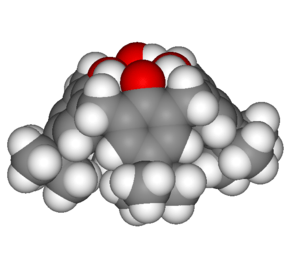

Calixarenes are the general category of macrocycle oligomers formed by hydroxyalkylation of a phenol and an aldehyde;[12] Resorcinarenes are one example. Calixarenes resemble chalices (calix in Latin) with hydrophobic cavities that can hold smaller molecules or ions, an example of host-guest chemistry. Raston has demonstrated a green chemistry approach to pyrogallol[4]arene from isovaleraldehyde (3-methylbutanal) and pyrogallol (1,2,3-benzenetriol) with a catalytic amount of p-toluenesulfonic acid.[11] He also produced a ball-and-socket supramolecular complex where calix[5]arene hosts the C70 fullerene.[13] The five phenyl groups forming the walls of the cavity interact with the aromatic fullerene through π stacking.

Unboiling an egg

Ovalbumin is the protein which makes up around two-thirds of the white of an egg.[14] When an egg is cooked, the ovalbumin changes conformation from its folded and soluble form to an insoluble all-β-sheet structure with exposed hydrophobic regions, leading to aggregation.[15] This is a classic example of protein denaturation, defined as the loss of the quaternary, tertiary and secondary structures that are present in the protein's native state, by application of some external chemical or radiative stress (including heat).[16] In order to "unboil" the egg, the individual protein strands must be separated from the aggregate and then re-folded back to their native form.[17] Raston had the idea of using mechanical energy from spinning the aggregate to achieve this and developed vortex fluidic technology to implement his idea.[18] Using it to unboil an egg (at least in part) was meant as a demonstration of the technology and won Raston and colleagues the 2015 Ig Nobel Prize in chemistry.[3] Applications of the technology include boosting the potency of anti-cancer drugs like carboplatin[19] and improving the production of biodiesel.[20]

Honours and awards

Raston was recognised for his professional achievements with Fellowships in the Royal Australian Chemical Institute (RACI) and the Royal Society of Chemistry.[1] On 13 June 2016, Governor-General, Sir Peter Cosgrove announced that Raston had been made an Officer of the Order of Australia in the Queen's Birthday Honours List, for "distinguished service to science through seminal contributions to the field of chemistry as a researcher and academic, and to professional associations."[4]

Raston served as the Vice President of the RACI in 1995–96, winning the H. G. Smith Memorial Medal that year,[1] and went on to serve as President the following year.[2] He has received several RACI awards, including the Burrows Award in 1994, which is the premier award of the Inorganic Chemistry Division of the RACI. In 2002, he was recognised with the Green Chemistry Challenge Award and went on to take the Leighton Memorial Medal,[2] the institute's most prestigious medal given in recognition of eminent services to chemistry in Australia, in 2006. He was named an RACI Living Luminary and in 2013 was appointed as the South Australia Premier's Professorial Research Fellow in Clean Technology.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Professor Colin Raston". Flinders University. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Royal Australian Chemical Institute Awards and Office Bearers". Royal Australian Chemical Institute. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Improbable Research – The 2015 Ig Nobel Prize Winners". www.improbable.com. 17 September 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 "The Queen's Birthday 2016 Honours List: Officer (AO) in the General Division of the Order of Australia" (PDF). Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. p. 41. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Edmonds, J. S.; Francesconi, K. A.; Cannon, J. R.; Raston, C. L.; Skelton, B. W.; White, A. H. (1977). "Isolation, crystal structure and Synthesis of arsenobetaine, the arsenical constituent of the Western Rock Lobster Panulirus longipes cygnus George". Tetrahedron Letters. 18 (18): 1543–1546. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)93098-9.

- ↑ Francesconi, K. A. (2005). "Current perspectives in arsenic environmental and biological research". Environmental Chemistry. 2 (3): 141–145. doi:10.1071/EN05042.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, P.; Welch, A. H.; Stollenwerk, K. G.; McLaughlin, M. J.; Bundschuh, J.; Panaullah, G. (2007). "Arsenic in the environment: Biology and chemistry". Science of the Total Environment. 379 (2–3): 109–120. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.02.037.

- ↑ Adair, B. M.; Waters, S. B.; Devesa, V.; Drobna, Z.; Styblo, M.; Thomas, D. J. (2005). "Commonalities in metabolism of arsenicals". Environmental Chemistry. 2 (3): 161–166. doi:10.1071/EN05054.

- ↑ Högberg, A. G. S. (1980). "Two stereoisomeric macrocyclic resorcinol-acetaldehyde condensation products". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 45 (22): 4498–4500. doi:10.1021/jo01310a046.

- ↑ Högberg, A. G. S. (1980). "Cyclooligomeric phenol-aldehyde condensation products. 2. Stereoselective synthesis and DNMR study of two 1,8,15,22-tetraphenyl[14]metacyclophan-3,5,10,12,17,19,24,26-octols". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 102 (19): 6046–6050. doi:10.1021/ja00539a012.

- 1 2 Antesberger, J; Cave, G. W.; Ferrarelli, M. C.; Heaven, M. W.; Raston, C. L.; Atwood, J. L. (2005). "Solvent-free, direct synthesis of supramolecular nano-capsules". Chemical Communications. 2005 (7): 892–894. doi:10.1039/b412251h.

- ↑ Gutsche, C. D. (1989). Calixarenes. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 085186385X.

- ↑ Atwood, J. L.; Barbour, L. J.; Heaven, M. W.; Raston, C. L. (2003). "Association and orientation of C70 on complexation with calix[5]arene". Chemical Communications. 2003 (18): 2270–2271. doi:10.1039/B306411P.

- ↑ Huntington, J. A.; Stein, P. E. (2001). "Structure and properties of ovalbumin". Journal of Chromatography B. 756 (1–2): 189–198. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(01)00108-6.

- ↑ Hu, H. Y.; Du, H. N. (2000). "α-to-β Structural transformation of ovalbumin: Heat and pH effects". Journal of Protein Chemistry. 19 (3): 177–183. doi:10.1023/A:1007099502179.

- ↑ Mosby's Medical Dictionary (9th ed.). Elsevier. 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Yuan, T. Z.; Ormonde, C. F. G.; Kudlacek, S. T.; Kunche, S.; Smith, J. N.; Brown, W. A.; Pugliese, K. M.; Olsen, T. J.; Iftikhar, M.; Raston, C. L.; Weiss, G. A. (2015). "Shear-stress-mediated refolding of proteins from aggregates and inclusion Bodies". ChemBioChem. 16 (3): 393–396. doi:10.1002/cbic.201402427.

- ↑ Seidel, J. (23 September 2015). "Over-cooked? Flinders University professor Colin Raston gets Ig Nobel Prize for 'unboiling an egg'". news.com.au. News Corporation. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Strom, M. (22 May 2015). "Machine that 'uncooks eggs' used to improve cancer treatment". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ↑ Eacott, A. (22 May 2015). "Cancer drug more effective after use of vortex fluidic device invented by Australian researcher". abc.net.au. ABC (Australia). Retrieved 14 June 2016.