Elwood (sternwheeler)

Elwood at Portland, Oregon. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Elwood |

| Owner: | Elldredge & Abernethy Bros. |

| Operator: | Lewis River Transportation Co. |

| Route: | Willamette, Lewis, Stikine rivers; Puget Sound |

| Completed: | 1891, at Portland, Oregon |

| Identification: | U.S. Steamboat registry #136181 |

| Fate: | Burned, 1904 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | riverine passenger/freight |

| Tonnage: | 510.44 gross; 413 net tonnage. |

| Length: | 154.0 ft (46.9 m) measured over hull. |

| Beam: | 30 ft 0 in (9.1 m) measured over hull. |

| Draft: | 4 ft 0 in (1.2 m) when fully loaded; 16 in (406.4 mm) with no cargo |

| Depth: | 7.0 ft 0 in (2.13 m) |

| Installed power: | twin steam engines, horizontally mounted, each with a bore of 13 in (330.2 mm) and stroke of 6 ft (1.83 m) |

| Propulsion: | sternwheel |

Elwood was a sternwheel steamboat which was built to operate on the Willamette River, in Oregon, but which later operated on the Lewis River in Washington, the Stikine River in Canada, and on Puget Sound. The name of this vessel is sometimes seen spelled "Ellwood". Elwood is probably best known for an incident in 1893, when it was approaching the Madison Street Bridge over the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon. The bridge swung open to allow the steamer to pass. However, a streetcar coming in from the east end of the bridge failed to notice the bridge was open, and ran off into the river in the Madison Street Bridge disaster.

Construction

Elwood was built in 1891 at Portland, Oregon by Johnston & Oleson, for the concern of Jason Eldridge and the three brothers Guy V. Abernethy, Charles H. Abernethy, and George Abernethy, of Champoeg, Oregon.[1][2][3][4] Another source gives the builder as Joseph Pacquart.[5] The Abernethy brothers were descendants of George Abernethy (c1807-1877), provisional governor of Oregon.[4]

The owners placed Elwood on the Willamette River, operating first with Capt. J.L. Smith, who was followed by Capt. R. Young and then by Captain James Lee, who as of 1895 had been in charge of the vessel for about 3 years.[2]

Elwood was intended to operate in opposition to the O.R.&N., and another line, the Oregon Pacific.[5][6]

Design, size, engineering and accommodations

Design and size

Elwood was intended to be a shallow-draft boat capable of passing the Clackamas Rapids on the lower Willamette and of operating on the upper Willamette river when water levels were down.[5][7] It was said that Elwood was "built to run on a heavy dew".[8] Elwood was so lightly built that it could not operate on longer runs on the Columbia such as to the Cascades or Astoria, Oregon.[8]

The official steamboat registry number was 136181.[9]

Elwood's official registered dimensions were 154.0 ft (46.9 m) measured over hull (not counting the rather long extension of the main deck which housed the sternwheel), 30.0 ft (9.1 m) beam, again measured over the hull, and not counting the guards, which were low strakes of timbers placed along the outboard top of the hull as a protective measure.[9] Depth of hold was 7 ft (2.1 m).[9] The vessel’s tonnage, a measure of capacity and not weight, was 510.44 gross tons and 420.54 net tons.[9] The boat drew only 13 in (330.2 mm) of water when light (empty of cargo and passengers).[1] With 100 tons of freight loaded, the vessel was expected to draw only about 25–26 in (635.0–660.4 mm) of water.[1]

Engineering

Elwood was powered by twin horizontally-mounted steam engines, each with a 14 in (355.6 mm) bore and a 72-inch stroke.[1][2] The engines were manufactured by Iowa by the Dubuque Iron Works, and were of the Poppet-valve type.[1] The boiler had 186 8 in (203.2 mm) tubes, each 14 ft (4.3 m) long.[1] The boiler was licensed to produce steam at 165 pounds pressure.[10] Engine room signals were given from the pilot house by speaking tube, and manual and electric bells.[1] There was a fog bell on the upper deck.[1]

Accommodations

Elwood had cabins forward and aft, and six staterooms.[1] With a special license, Elwood would be able to legally carry 250 passengers.[1]

Service on the Willamette River

Elwood made its trial trip on Wednesday afternoon, May 27, 1891.[1] Elwood departed the Portland & Willamette Valley dock shortly after 4:00 pm., and proceeded a few miles downriver.[1] The owners had invited on board guests for the trial trip, including a number from Salem, among whom were representatives of the two Salem newspapers.[1]

Robert Young was the first captain of Elwood, and Charles Abernethy was the boat’s first manager.[4]

The next day, Thursday, May 28, 1891, Elwood left the Kellogg dock in Portland, and was expected to arrive in Salem that same evening to load freight.[1]

Hit snag and sunk

At about 6:00 p.m. on Tuesday August 25, 1891, while carrying passengers and a cargo of 500 sacks of oats, Elwood hit a snag at Ash Island, about 35 miles south of Portland, and sank.[11] The steamer had just left the mouth of the Yamhill River, and, with mate John Ditmer at the wheel, was running in a stretch of deeper water close to shore known as Ash Island channel.[11] Here the vessel ran into a snag which was about one foot under the surface of the water and about 20 feet from shore.[11] The current spun the boat around sidewise and the snag ripped a hole half the length of the hull, sinking the vessel cabin-deep, and rendering cargo of oats a total loss.[11] There was no casualty to the passengers, and they were easily brought off the boat to the river bank.[11]

Total damage was estimated at $1,000, of which $400 represented damage to the cargo.[11] Plans were made immediately to raise Elwood and bring it downriver for repairs.[11]

1892 and 1893 operations

Racing brings criminal charges

On May 4, 1892, Elwood left Salem at the same time as the steamer Hoag.[10] A race followed, and the crew of Elwood claimed they won.[10] On Monday, May 9, 1892, E.A. Kern, the chief engineer of Elwood, was arrested and charged with disabling the safety valve on Elwood's boiler, so that steam at 195 pounds pressure could be raised, instead of the 165-pound maximum that was allowed on the boiler’s certificate.[10] The assistant engineer, T.C. Fitzgerald, was also arrested on similar charges.[10]

On Friday, May 13, 1892, Kern was brought before U.S. Commissioner Paul H. Deady the day after the arrest, and he posted bond of $500 to secure his release during the pendency of the case.[10] If convicted, Kern would have faced a potential file of $200 and a maximum prison sentence of five years.[10] The Morning Oregonian wrote at the time:

Now that the picnic and excursion season is on, and the seaside season at hand, the officers of steamboats will do well to take warning from the arrest of the Elwood’s engineers and not indulge in racing, especially with more steam than they are allowed to carry.[10]

Collision with Stark Street Ferry

On the evening of October 29, 1892, when Elwood was tied to the wharf at Alder Street, in Portland, the Stark Street Ferry ran into the sternwheeler.[12] Elwood's fantail was badly damaged, as was the tackle on the ferry.[12] The ferry was forced to suspend operations for two hours to make repairs. Damage to both vessels was estimated at $25.[12] No one was blamed for the accident, as it was quite dark and the ferry captain thought there was enough room to make a safe landing.[12]

Portland–Albany run

As of May 5, 1893, Elwood was running twice a week between Portland and Albany, Oregon.[13]

Madison Street bridge disaster

Elwood was involved in the Madison Street Bridge streetcar disaster, when on the morning of November 1, 1893, the swinging draw section of the Madison Street Bridge, in Portland, opened to allow passage of the boat, and a streetcar on the bridge failed to stop for the open draw.[7]

1894 operations

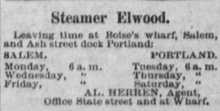

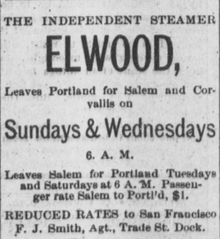

1894 schedule

As of April 5, 1894, Elwood departed Portland for Salem and Corvallis on Sundays and Wednesdays at 6:00 a.m.[14] Elwood left Salem for Portland Tuesdays and Saturdays at 6:00 a.m.[14] The passenger fare from Salem to Portland was $1.00.[14] Frank J. Smith, with an office at the Trade Street Dock, was the Salem agent for the steamer.[14] Smith had taken over the Salem agency for Elwood from Albert Herren, reportedly a popular steamboat agent, in November 1893.[15]

Loss of an engineer

On April 10, 1894, Willam Armstrong, second engineer, was lost off the Elwood while the boat was en route from Oregon City to Salem.[16][17] The incident occurred near Fairfield,[17] which was 16 miles downriver from Salem.[18]

No one saw Armstrong go overboard.[16] The chief engineer stepped out of the engine room briefly, and when he returned, he noticed Armstrong missing.[16] An oil can was also missing, and Armstrong’s cap was on the machinist’s bench.[16] The supposition was that Armstrong had gone out on the fan tail to oil the sternwheel bearings, slipped off, and fell into the river.[16] A few days previously Armstrong had told Captain Lee that he could not swim.[16]

On May 10, 1894, Armstrong’s body was found in the boom of the old Mission Mill, about 18 miles downriver from where he had been lost.[19] Two wounds on the body’s head were thought to be consistent with the theory that he had been struck on the head by the buckets of the paddle wheel.[19] Armstrong’s gold watch was found still attached to his vest by the chain.[19] The body was taken to Oregon City, where his parents resided, for burial.[19]

Rate war with Union Pacific

In early 1894, the Union Pacific Railroad placed a steamboat on the upper Willamette River, the Modoc, to compete with Elwood.[20] Before placing Modoc into service, the Union Pacific had cooperated with Elwood, allowing the independent steamer to use the railroad’s dock at Salem.[20] However, on April 1, 1892, Union Pacific sent a telegram to their Salem agent, instructing him to no longer allow Elwood to use their dock.[20] Elwood's owners shifted over immediately to the Oregon Pacific floating wharf.[20] George E. Abernethy was Elwood's manager at the time.[20] The fare war reduced shipping rates which benefited the merchants of Salem.[20]

Transfer to Lewis River service

On May 26, 1894, Charles H. Abernethy was reported to come to Salem to close up the business of the Elwood, which he had tied up at his residence at Champoeg.[21] Abernethy did not expect to be running the vessel before fall.[21]

In 1894, Elwood was leased by the Lewis River Transportation Service to replace Mascot on the Lewis River run.[2] A non-contemporaneous source states that it was the very successful steamboatman Jacob Kamm who leased Elwood for the Portland – Lewis River route.[4] Kamm appears to have controlled the Lewis River Transportation company, and he may have purchased rather than leased Elwood.[5]

The Abernethy brothers were reported to have lacked the necessary experience in steamboating and to have returned to farming after having been bested by the competition.[5]

1895 wheat harvest in the Willamette valley

In August 1895, it was reported that "an immense lot of wheat" was being delivered to the Imperial Mills at Oregon City from landings on the upper Willamette River.[22] As of August 23, 1895, Elwood had been engaged for ten days carrying wheat from Mission Landing (near St. Paul[23]) and other points on the upper river to the mills at Oregon City.[22]

1896 and 1897 operations

Race with Hattie Belle

Despite the 1892 arrest of Engineer Kern for complicity in a steamboat race, Elwood was again involved in a race in 1896, with the sternwheeler Hattie Belle.[24] Hattie Belle entered the Willamette River from the Columbia about 200 yards ahead of Elwood, which overtook Hattie Bell at Post Office Bar.[24] Post Office Bar was a short distance from the mouth of the Willamette.[25] As Elwood passed Hattie Belle, the two vessels came so close together that Hattie Belle was carried along in the suction created by the passage of Elwood, a larger vessel.[24] The two boats ran this manner all the way to the Steel Bridge.[24] This was a distance of 12.1 miles from the mouth of the Willamette. At the Steel Bridge, the two boats separated, and Hattie Belle was able to pull into the dock first.[24]

Reassignment to upper Willamette

In late September 1896, Elwood was tied up and undergoing extensive repairs at Jacob Kamm’s dock in Portland at Taylor Street.[8] Kamm had not yet decided whether to place Elwood back on the upper Willamette route.[8] There were already about ten steamers operating on the upper Willamette at that time, and it wasn’t clear whether there would be enough business to support another.[8] Kamm, however, did not seem to be particularly concerned, saying that "when a man owned steamers, he had to run them somewhere."[8]

Hop season 1897

To meet the needs for carriage of pickers for the 1897 hops season in the Willamette Valley, Elwood was engaged by the Oregon City Transportation Company, leaving Portland on the morning of August 27, 1897, to carry pickers as far upriver as the water conditions, generally low at the end of the summer, would permit.[26]

Elwood operated on the upper Willamette to transport pickers for the hop season.[27] 2,500 people from Portland sought transport to the hop yards for picking work.[27] On Sunday morning, August 29, 1897, both Elwood and another sternwheeler, Altona, transported a full load of passengers, most of whom were landed at Butteville.[27] Some were taken further upriver to Salem by the steamer Ramona, where they arrived at 9:45 pm Sunday night.[27]

Transfer to the Stikine River

In 1898, with the coming of the Alaska Gold Rush, Elwood was sent north to Alaska to run on the Stikine River, where there was an effort being made to develop an alternative "All-Canadian" route to the Klondike gold fields.[28][29]

Sale to Canadian interests

In 1898, Elwood was sold to an Alaskan company and transferred to the Stikine River in British Columbia.[3][4]

On February 6, 1898, it was reported that a Canadian shipbuilder, W.J. Stephens, while in Portland, had, on behalf of Victoria, BC interests, purchased Elwood from the Lewis River Transportation Company[30] The new owner was reported in one source to be the Lake Bennett & Klondike Navigation Company.[31] Another source gives the new owner as the Cassiar Central Railway.[32] Still a third source states the new owner was the Canadian Pacific.[5]

Tow to Alaska

On Monday afternoon, April 18, 1898, Elwood departed Portland in the tow of the tug Relief bound for the Stikine River.[33] Captain Johnson, who had once commanded the Columbia River sternwheeler Dalles City, was in charge of the vessel.[33] Charles Jennings was the engineer.[33] The total complement was 16.[33] No equipment or supplies were loaded, other than those necessary for the crew for the trip north.[33]

Elwood in tow of Relief was scheduled to depart Astoria, Oregon early in the morning on Wednesday, April 20, 1898, for Puget Sound and thereafter to Alaska.[34]

Relief was a powerful steel tug built by sugar magnate Claus Spreckels.[33] Relief had completed the tow of the former Willamette River steamer Ramona to the Stikine earlier the same year.[33]

Elwood arrived in Victoria, BC on April 21, 1898, and was expected to depart soon for the north for survey and construction work, with a crew of 15 and Captain Johnson in command.[32]

Operations on the Stikine

By May 8, 1898, Elwood had arrived at Fort Wrangell and departed up the Stikine River bound for Glenora, British Columbia.[35] Elwood was then one of seven sternwheelers to have steamed up the river for Glenora, which was a four-day round trip from Fort Wrangell.[35] By May 22, 1898, Elwood had completed two round trips.[36]

Closure of the Stikine route

By the summer of 1898, the Stikine route had failed due to the extreme difficulty of reaching gold fields overland from the steamboat terminus.[29][37] Elwood performed well on the Stikine River, carrying 200 tons of cargo or 250 passengers.[4] After a year on the Stikine River, Elwood was reported to have been transferred to the Fraser River.[4][38] Another source states that Elwood was transferred to Ketchikan, Alaska.[5]

Operations on Puget Sound

In the early 1900s, Elwood was operated on Puget Sound by Capt. H.H. McDonald, (c.1857-1924), who also operated Skagit Queen, and, after 1903, Multnomah and Capital City.[37] McDonald was doing business as the McDonald Steamship Company.[5] Elwood was placed on a route between Seattle and Tacoma.[7]

Loss by fire

On August 16, 1904, while unloading freight at Avon, Washington, Elwood caught fire and burned.[39] The fire’s origin was unknown.[39] The total value of the loss was reported to have been $12,000.[39] The steamer had just pulled up to the landing at Avon, on the Skagit River.[5]

Some time between 2:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m., a fire started.[5][38] The fire's origin has been reported conflictingly in the contemporaneous sources. One source says the fire began in the forecastle.[5] Another source says the fire started in the engine room.[38] All sources agree that wherever it started, the fire quickly spread, and the vessel became a total loss.[5] The machinery was so damaged that it was "practically worthless."[5] The crew was said to have "narrowly escaped with their lives."[40]

Elwood was reported to have been worth about $15,000.[38] Elwood's place on the route would be taken over by the Skagit Queen.

Historical remembrance

A photograph of Elwood was chosen to be featured on the membership cards of the Veteran Steamboatmen’s Association for 1942.[41] Two of the first owners of Elwood, Guy V. Abernethy and Charles H. Abernethy, were still living in 1942, at Ocean Park, Washington, and were honored at the 17th Annual Meeting of the Veteran Steamboatmen of the West, held at Jantzen Park, Portland, Oregon, on Sunday, June 28, 1942.[4][42]

The Elwood Building, part of the Hassalo on Eighth apartment complex in Portland's Lloyd District, is named after the steamboat.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "New Steamer Elwood: Her Trial Trip in Portland a Success Owned by Marion County Men". Evening Capital Journal. Salem, OR. May 28, 1891. p. 3 col. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). Lewis & Dryden's Marine history of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. 388. LCCN 28001147.

- 1 2 "Pioneer Wife Dies at 70: Abernethy Name Recalls River Lore". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barber, Lawrence (June 7, 1942). "Ancient Steamer to be Honored: Sternwheeler to Feature Steamboatmen Reunion". The Sunday Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. Section 5, p.7, col.2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Portland-Built Boat Burned: Elwood is a Total Loss on the Skagit River". Morning Oregonian. Portland, OR. August 21, 1904. p. 12 col. 1.

- ↑ A non-contemporaneous source states that Elwood was built for the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (O.R. & N). Timmen, Fritz (1973). Blow for the Landing -- A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. 59–60. ISBN 0-87004-221-1. LCCN 73150815.. However, based on contemporaneous sources, it appears that Elwood was built to compete against the O.R.&N.

- 1 2 3 Timmen, Fritz (1973). Blow for the Landing -- A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. 59–60. ISBN 0-87004-221-1. LCCN 73150815.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "On the Willamette: The Steamer Elwood May Appear as Opposition Steamer". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. September 25, 1896. p. 7 col. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 U.S. Dept. of the Treasury, Statistics Bureau (1894). Annual List of Merchant Vessels (for year ending June 30, 1893). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Steamboat Racing: The Elwood's Engineer Arrested for Carrying too Much Steam". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. May 14, 1892. p. 8 col. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Struck a Snag: The Steamer Elwood Wrecked in Fourteen Feet of Water". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. August 27, 1891. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Slight Collision". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. October 30, 1892. p. 15 col. 3.

- ↑ "Salem Notes". Morning Oregonian. Portland, OR. May 5, 1893. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, F.J. (April 5, 1894). "The Independent Steamer Elwood … (advertisement)". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. p. 3 col. 4.

- ↑ "Personals". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. November 21, 1893. p. 4 col. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Missing". The Dalles Times-Mountaineer. The Dalles, OR. April 14, 1894. p. 3 col. 2.

- 1 2 "Drowned in the Willamette". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. April 12, 1894. p. 2 col. 2.

- ↑ Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). "Wheat Ports of the Middle River … Fairfield Landing". Willamette Landings -- Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. pages 89-94. ISBN 0875950426.

- 1 2 3 4 "City News in Brief: Body Recovered". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. May 11, 1894. p. 5 col. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A Steamboat War: The Union Pacific Forces the Independent Boat to Seek a New Wharf". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. April 2, 1894. p. 1 col. 6.

- 1 2 "C.H. Abernethy, of Champoeg, was in the city today closing up business …". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. May 26, 1894. p. 4 col. 4.

- 1 2 "An immense lot of wheat is coming to the Imperial mills …". Oregon City Enterprise. Oregon City, OR. August 23, 1895. p. 6 col. 1.

- ↑ Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). Willamette Landings -- Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0875950426.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Race on the River: Steamers Elwood and Hattie Belle". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. August 7, 1896. p. 8.

- ↑ "Post Office Bar to be Improved". Sunday Oregonian. Portland, OR. March 8, 1914. Section Two p. 20 col. 1.

- ↑ "An Extra Boat". Daily Capital Journal. Salem, OR. August 27, 1897. p. 4 col. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 "In the Hop Yards: Picking Will be General Throughout the Valley This Week". Daily Capital Journal. Salem, OR. August 30, 1897. p. 4 col. 4.

- ↑ Affleck, Edward L. (2000). A Century of Paddlewheelers in the Pacific Northwest, the Yukon, and Alaska. Vancouver, BC: Alexander Nicholls Press. ISBN 0-920034-08-X.

- 1 2 Turner, Robert D. (1984). Sternwheelers and Steam Tugs: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Pacific Railway's British Columbia Lake and River Service (1st ed.). Victoria, BC: Sono Nis Press. pages 69 to 97. ISBN 0919203159.

- ↑ "Local Fleet Growing: Activity in Yukon Business Causing Frequent Additions". Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. February 6, 1898. p. 7 col. 5.

- ↑ "Marine Notes". Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. February 17, 1898. p. 3 col. 1.

- 1 2 "The Elwood Arrives". Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. April 22, 1898. p. 7 col. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The stern-wheel steamer Elwood, purchased about two months ago …". The Dalles Daily Chronicle. The Dalles, OR. April 21, 1898. p. 3 col. 4.

- ↑ "The steamer Elwood in tow of the tug Relief, sails early this morning …". Daily Morning Astorian. Astoria, OR. April 20, 1898. p. 4 col. 1.

- 1 2 Watson, Louis (May 15, 1898). "Stikine a Success". Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. p. 7 col. 2.

- ↑ "On Northern Trails". Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. May 22, 1898. p. 5 col. 3.

- 1 2 Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: Superior Pub. Co. pp. 37, 88, 249, 358. LCCN 66025424.

- 1 2 3 4 "Steamer Elwood Burned: Vessel Built on the Columbia Destroyed on the Skagit River". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. August 17, 1904. p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Department of Commerce and Labor (1905). "Report of the Supervising Inspector-General Steamboat Inspection Service". Reports of the Department of Commerce and Labor. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p.336.

- ↑ "Part II: Chapter V: Skagit County, 1897-1905: Burning of Steamer Elwood". An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish County. Chicago, IL: Interstate Publishing. 1906. p.173.

- ↑ "Vets Cancel Picnic Plans". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. May 15, 1942. p. 14 col. 2.

- ↑ "Boat Veterans Picnic Sunday: Old-Times, Wives Plan Reunion". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. June 27, 1942. p. 22.

References

Printed sources

- Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). Willamette Landings -- Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0875950426.

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: Superior Pub. Co. LCCN 66025424.

- Timmen, Fritz (1973). Blow for the Landing -- A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. ISBN 0-87004-221-1. LCCN 73150815.

- Turner, Robert D. (1984). Sternwheelers and Steam Tugs: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Pacific Railway's British Columbia Lake and River Service (1st ed.). Victoria, BC: Sono Nis Press. ISBN 0919203159.

On line historic newspaper collections

- "Historic Oregon Newspapers". University of Oregon.

- "The Historical Oregonian (1861-1987)". Multnomah County Library.

- "The British Colonist (1858-1920)". University of Victoria.