Yokosuka D4Y

| D4Y | |

|---|---|

| |

| Yokosuka D4Y3 Model 33 "Suisei" in flight | |

| Role | Dive bomber |

| Manufacturer | Yokosuka |

| First flight | December 1940 |

| Introduction | 1942 |

| Retired | 1945 |

| Primary user | IJN Air Service |

| Produced | 1942–1945 |

| Number built | 2,038 |

|

| |

The Yokosuka (横須賀) D4Y Suisei (彗星 "Comet") Navy Carrier Dive bomber was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Its Allied reporting name was "Judy". The D4Y was one of the fastest dive-bombers of the war and only the delays in its development hindered its service while its predecessor, the slower fixed-gear Aichi D3A, remained in service much longer than intended. Despite limited use, the speed and the range of the D4Y were nevertheless valuable, and the type was used with success as reconnaissance aircraft as well as for kamikaze missions.

Design and development

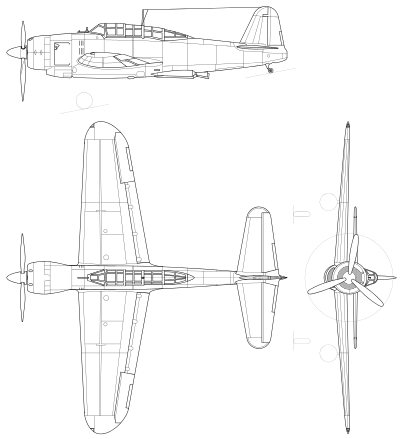

Development of the aircraft began in 1938 at the Yokosuka Naval Air Technical Arsenal as a carrier-based dive bomber to replace the Aichi D3A. The aircraft was a single-engine, all-metal low-wing monoplane, with a wide-track retractable undercarriage and wing-mounted dive brakes. It had a crew of two: a pilot and a navigator/radio-operator/gunner, seated under a long, glazed canopy which provided good all-round visibility. The pilot of bomber versions was provided with a telescopic bombsight.[1] The aircraft was powered by an Aichi Atsuta liquid-cooled inverted V12 engine, a licensed copy of the German DB 601, rated at 895 kW (1,200 hp). The radiator was behind and below the three-blade propeller, as in the P-40 Warhawk.

The aircraft had a slim fuselage that enabled it to reach high speeds in horizontal flight and in dives, while it had excellent maneuverability despite high wing loading, with the Suisei having superior performance to contemporary dive bombers such as the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver.[2] In order to conform with the Japanese Navy's requirement for long range, weight was minimized by not fitting the D4Y with self-sealing fuel tanks or armour.[3] In consequence, the D4Y was extremely vulnerable and tended to catch fire when hit.

Bombs were fitted under the wings and in an internal fuselage bomb bay. It usually carried one 500 kg (1,100 lb) bomb but there were reports that the D4Y sometimes carried two 250 kg (550 lb) bombs, for example during the attack on the light aircraft carrier USS Princeton; only 30 kg (70 lb) bombs were carried externally. The aircraft was armed with two 7.7 mm (.303 in) Type 97 aircraft machine guns in the nose and a 7.92 mm (.312 inm) Type 1 machine gun selected for its high rate of fire, in the rear of the cockpit. The rear gun was replaced by a 13 mm (.51 in) Type 2 machine gun. This armament was typical for Japanese carrier-based dive-bombers, unlike "carrier attack bombers" (i.e. torpedo bombers) like the Nakajima B5N and B6N which were not given forward-firing armament until the late-war Aichi B7A, which was expected to serve as both a dive-bomber and torpedo-bomber, and was given a pair of 20mm Type 99-2 cannon. The forward machine guns were retained in the kamikaze version.

The first (of five) prototypes made its maiden flight in December 1940.[4][5] After the prototype trials, problems with flutter were encountered, a fatal flaw for an airframe subject to the stresses of dive bombing. Until this could be resolved, early production aircraft were used as reconnaissance aircraft, as the D4Y1-C, which took advantage of its high speed and long range, while not over-stressing the airframe.[2] Production of the D4Y1-C continued in small numbers until March 1943, when the increasing losses incurred by the D3A resulted in production switching to the D4Y1 dive-bomber, the aircraft's structural problems finally being solved.[3] Although the D4Y could operate from the large fleet carriers that formed the core of the Combined Fleet at the start of the war, it had problems operating from the smaller and slower carriers such as the Hiyō class which formed a large proportion of Japan's carrier fleet after the losses of the Battle of Midway. Catapult equipment was fitted, giving rise to the D4Y1 Kai (or improved) model.[3]

Early versions of the D4Y were difficult to keep operational because the Atsuta engines were unreliable in front-line service. From the beginning, some had argued that the D4Y should be powered by an air-cooled radial engine which Japanese engineers and maintenance crew had experience with, and trusted. The aircraft was re-engined with the reliable Mitsubishi MK8P Kinsei 62, a 14-cylinder two-row radial engine as the Yokosuka D4Y3 Model 33.

Although the new engine improved ceiling and rate of climb (over 10,000 m/32,800 ft, and climb to 3,000 m/9,800 ft in 4.5 minutes, instead of 9,400 m/30,800 ft and 5 minutes), the higher fuel consumption resulted in reduced range and cruising speed and the engine obstructed the forward and downward view of the pilot, hampering carrier operations. These problems were tolerated because of the increased availability of the new variant.[6]

The last version was the D4Y4 Special Strike Bomber, a single-seat kamikaze aircraft, capable of carrying one 800 kg (1,760 lb) bomb, which was put into production in February 1945. It was equipped with three RATO boosters for terminal dive acceleration.[7] This aircraft was an almost ideal kamikaze model: it had a combination of speed (560 km/h/350 mph), range (2,500 km/1,550 mi) and payload (800 kg/1,760 lb) probably not matched by any other Japanese aircraft.

The D4Y5 Model 54 was a planned version designed in 1945. It was to be powered by the Nakajima NK9C Homare 12 radial engine rated at 1,361 kW (1,825 hp), a new four-blade metal propeller of the constant-speed type and more armour for the crew and fuel tanks. Ultimately, 2,038 of all variants were produced, mostly by Aichi.[8]

Operational history

Lacking armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, the Suiseis did not fare well against Allied fighters. They did, however, cause considerable damage to ships, including the carrier USS Franklin which was nearly sunk by an assumed single D4Y and the light carrier USS Princeton which was sunk by a single D4Y.

The D4Y was operated from the following Japanese aircraft carriers: Chitose, Chiyoda, Hiyō, Junyō, Shinyo, Shōkaku, Sōryū, Taihō, Unryū, Unyō and Zuikaku.

The D4Y1-C reconnaissance aircraft entered service in mid-1942, when two of these aircraft were deployed aboard Sōryū at the Battle of Midway, both of which were lost when Sōryū was sunk.[3]

Marianas

During the Battle of the Marianas, the D4Ys were engaged by U.S. Navy fighters and shot down in large numbers. It was faster than the Grumman F4F Wildcat, but not the new Grumman F6F Hellcat which entered combat in September 1943. The Japanese aircraft were adequate for 1943, but the rapid advances in American materiel in 1944 (among them, the introduction in large numbers of the Essex-class aircraft carrier) left the Japanese behind. Another disadvantage suffered by the Japanese was their inexperienced pilots.

The U.S. Task Force 58 struck the Philippine airfields and destroyed the land air forces first, before engaging Japanese naval aircraft. The result was what the Americans called "The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot", with 400 Japanese aircraft shot down in a single day. A single Hellcat pilot, Lieutenant Alexander Vraciu, shot down six D4Ys within a few minutes.

One D4Y was said to have damaged the battleship USS South Dakota.

Leyte and Philippines

The D4Y was relegated to land operations where both the liquid-cooled engine D4Y2, and the radial engine D4Y3 fought against the U.S. fleet, scoring some successes. An unseen D4Y bombed and sank the Princeton on 24 October 1944. D4Ys hit other carriers as well, by both conventional attacks and kamikaze actions. In the Philippines air battles, the Japanese used kamikazes for the first time, and they scored heavily. D4Ys from 761 Kōkūtai may have hit the escort carrier USS Kalinin Bay on 25 October 1944, and the next day, USS Suwannee. Both were badly damaged, especially Suwannee, with heavy casualties and many aircraft destroyed. A month later on 25 November, USS Essex, Hancock, Intrepid and Cabot were hit by kamikazes, almost exclusively A6M Zero fighters and D4Ys, with much more damage. D4Ys also made conventional attacks. All these D4Ys were from 601 and 653 Kōkūtai.

In defense of the homeland

Task Force 58 approached southern Japan in March 1945 to strike military objectives in support of the invasion of Okinawa. The Japanese responded with massive kamikaze attacks, codenamed Kikusui, in which many D4Ys were used. A dedicated kamikaze version of the D4Y3, the D4Y4 with a non-detachable 800 kg bomb attached in a semi-recessed manner, was developed. The Japanese had begun installing rocket boosters on some Kamikazes, including the D4Y4 in order to increase speed near the target. As the D4Y4 was virtually identical in the air to the D4Y3, it was difficult to determine the sorties of each type.[9]

Carriers USS Enterprise and Yorktown were damaged by D4Ys of 701 Wing on 18 March. On 19 March, the carrier USS Franklin was hit with two bombs from a single D4Y, which then escaped despite heavy anti-aircraft fire. Franklin was so heavily damaged that she was retired until the end of the war. Another D4Y hit the carrier USS Wasp.

On 12 April 1945, another D4Y, part of Kikusui mission N.2, struck Enterprise, causing some damage.

During Kikusui N.6, on 11 May 1945, USS Bunker Hill was hit and put out of action by two kamikazes that some sources identify as D4Ys. This was the third Essex-class carrier forced to retire to the United States to repair.

Night fighter

The D4Y was faster than the A6M Zero and some were employed as D4Y2-S night fighters against Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers late in the war. The night fighter conversions were made at the 11th Naval Aviation Arsenal at Hiro. Each D4Y2-S had their bombing systems and equipment removed, and replaced with a 20 mm Type 99 cannon with its barrel slanted up and forwards, in a similar manner to the German Schräge Musik armament fitment (pioneered in May 1943 on the Nakajima J1N by the IJNAS) installed in the rear cockpit. Some examples also carried two or four 10 cm air-to-air rockets under the wings; lack of radar for night interceptions, inadequate climb rate and the B-29's high ceiling limited the D4Y2-S effectiveness as a night fighter. Little is known of their operations.

Last action

At the end of the war, D4Ys were still being used operationally against the U.S. Navy. Among the last of these were 11 aircraft led by Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki on a search mission on 15 August 1945, of which all but three were lost.

Operators

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

- Aircraft carrier

- Battleship

- Naval Air Group

- Himeji Kōkūtai

- Hyakurihara Kōkūtai

- Kaikō Kōkūtai

- Kanoya Kōkūtai

- Kantō Kōkūtai

- Kinki Kōkūtai

- Kyūshū Kōkūtai

- Nagoya Kōkūtai

- Nansei-Shotō Kōkūtai

- Ōryū Kōkūtai

- Tainan Kōkūtai

- Taiwan Kōkūtai

- Tōkai Kōkūtai

- Tsuiki Kōkūtai

- Yokosuka Kōkūtai

- 12th Kōkūtai

- 121st Kōkūtai

- 131st Kōkūtai

- 132nd Kōkūtai

- 141st Kōkūtai

- 151st Kōkūtai

- 153rd Kōkūtai

- 201st Kōkūtai

- 210th Kōkūtai

- 252nd Kōkūtai

- 302nd Kōkūtai

- 352nd Kōkūtai

- 501st Kōkūtai

- 502nd Kōkūtai

- 503rd Kōkūtai

- 521st Kōkūtai

- 523rd Kōkūtai

- 531st Kōkūtai

- 541st Kōkūtai

- 552nd Kōkūtai

- 553rd Kōkūtai

- 601st Kōkūtai

- 634th Kōkūtai

- 652nd Kōkūtai

- 653rd Kōkūtai

- 701st Kōkūtai

- 721st Kōkūtai

- 722nd Kōkūtai

- 752nd Kōkūtai

- 761st Kōkūtai

- 762nd Kōkūtai

- 763rd Kōkūtai

- 765th Kōkūtai

- 901st Kōkūtai

- 951st Kōkūtai

- 1001st Kōkūtai

- 1081st Kōkūtai

- Aerial Squadron

- Reconnaissance 3rd Hikōtai

- Reconnaissance 4th Hikōtai

- Reconnaissance 61st Hikōtai

- Reconnaissance 101st Hikōtai

- Reconnaissance 102nd Hikōtai

- Attack 1st Hikōtai

- Attack 3rd Hikōtai

- Attack 5th Hikōtai

- Attack 102nd Hikōtai

- Attack 103rd Hikōtai

- Attack 105th Hikōtai

- Attack 107th Hikōtai

- Attack 161st Hikōtai

- Attack 251st Hikōtai

- Attack 263rd Hikōtai

- Kamikaze

- Chūyū group (picked from Attack 5th Hikōtai)

- Giretsu group (picked from Attack 5th Hikōtai)

- Kasuga group (picked from Attack 5th Hikōtai)

- Chihaya group (picked from 201st Kōkūtai)

- Katori group (picked from Attack 3rd Hikōtai)

- Kongō group No. 6 (picked from 201st Kōkūtai)

- Kongō group No. 9 (picked from 201st Kōkūtai)

- Kongō group No. 11 (picked from 201st Kōkūtai)

- Kongō group No. 23 (picked from 201st Kōkūtai)

- Kyokujitsu group (picked from Attack 102nd Hikōtai)

- Suisei group (picked from Attack 105th Hikōtai)

- Yamato group (picked from Attack 105th Hikōtai)

- Kikusui-Suisei group (picked from Attack 103rd Hikōtai and Attack 105th Hikōtai)

- Kikusui-Suisei group No. 2 (picked from Attack 103rd Hikōtai and Attack 105th Hikōtai)

- Koroku-Suisei group (picked from Attack 103rd Hikōtai)

- Chūsei group (picked from 252nd Kōkūtai and Attack 102nd Hikōtai)

- Mitate group No. 3 (picked from Attack 1st Hikōtai and Attack 3rd Hikōtai)

- Mitate group No. 4 (picked from Attack 1st Hikōtai)

- 210th group (picked from 210th Kōkūtai)

- Niitaka group (picked from Attack 102nd Hikōtai)

- Yūbu group (picked from Attack 102nd Hikōtai)

- United States Navy operated captured aircraft for evaluation purposes.

Variants

- D4Y1 Experimental Type 13 carrier dive-bomber (13試艦上爆撃機, 13-Shi Kanjō Bakugekiki)

- 5 prototypes were produced. #3 and #4 were rebuilt to reconnaissance plane and carried on aircraft carrier Sōryū.

- D4Y1-C Type 2 reconnaissance aircraft Model 11 (2式艦上偵察機11型, Nishiki Kanjō Teisatsuki 11-Gata)

- Reconnaissance version produced at Aichi's Nagoya factory. Developed on 7 July 1942.

- D4Y1 Suisei Model 11 (彗星11型, Suisei 11-Gata)

- First batch of serial produced dive bomber aircraft. Powered by 895 kW (1,200 hp) Aichi AE1A Atsuta 12 engine. Developed in December 1943.

- D4Y1 KAI Suisei Model 21 (彗星21型, Suisei 21-Gata)

- D4Y1 with catapult equipment for battleship Ise and Hyūga. Developed on 17 March 1944.

- D4Y2 Suisei Model 12 (彗星12型, Suisei 12-Gata)

- 1,044 kW (1,400 hp) Aichi AE1P Atsuta 32 engine adopted. Developed in October 1944.

- D4Y2a Suisei Model 12A (彗星12甲型, Suisei 12 Kō-Gata)

- D4Y2 with the rear cockpit 13 mm (.51 in) machine gun. Developed in November 1944.

- D4Y2a KAI Suisei Model 22A (彗星22甲型, Suisei 22 Kō-Gata)

- D4Y2a with catapult equipment for battleship Ise and Hyūga.

- D4Y2-S Suisei Model 12E (彗星12戊型, Suisei 12 Bo-Gata)

- Night fighter version of the D4Y2 with bomb equipment removed and a 20 mm upward-firing cannon installed.

- D4Y2 KAI Suisei Model 22 (彗星22型, Suisei 22-Gata)

- D4Y2 with catapult equipment for battleship Ise and Hyūga.

- D4Y2-R Type 2 reconnaissance aircraft Model 12 (2式艦上偵察機12型, Nishiki Kanjō Teisatsuki 12-Gata)

- Reconnaissance version of the D4Y2. Developed in October 1944.

- D4Y2a-R Type 2 reconnaissance aircraft Model 12A (2式艦上偵察機12甲型, Nishiki Kanjō Teisatsuki 12 Kō-Gata)

- D4Y2-R with the rear cockpit 13 mm (.51 in) machine gun.

- D4Y3 Suisei Model 33 (彗星33型, Suisei 33-Gata)

- Land-based bomber variant. 1,163 kW (1,560 hp) Mitsubishi Kinsei 62 radial engine adopted. Removed tailhook also.

- D4Y3a Suisei Model 33A (彗星33甲型, Suisei 33 Kō-Gata)

- D4Y3 with the rear cockpit 13 mm (.51 in) machine gun.

- D4Y3 Suisei Model 33 night-fighter variant (彗星33型改造夜戦, Suisei 33-Gata Kaizō yasen)

- Temporary rebuilt night-fighter version. Two planes were converted from D4Y3.[16] Equipment a 20 mm upward-firing cannon installed. This is not a naval regulation equipment. Development code D4Y3-S (or Suisei Model 33E) was not discovered in the IJN official documents.

- D4Y4 Suisei Model 43 (彗星43型, Suisei 43-Gata)

- Single seat kamikaze aircraft with 800 kg (1,760 lb) bomb and three RATO boosters.[17]

- D4Y5 Suisei Model 54 (彗星54型, Suisei 54-Gata)

- Planned version with Nakajima Homare radial engine, four-blade propeller, and more armor protection.

Survivors

A restored D4Y1 (serial 4316) is located at the Yasukuni Jinja Yūshūkan shrine in Tokyo.

An engineless D4Y1 was recovered from Babo Airfield, Indonesia in 1991. It was acquired and restored to non-flying status by the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California. It was restored to represent a radial engined D4Y3, using an American, Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine. The engine is in running condition and can be started to demonstrate ground running and taxing of the aircraft.[18]

Specifications (D4Y2)

Data from The Encyclopedia of World Aircraft[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: two (pilot & gunner/radio operator)

- Length: 10.22 m (33 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 11.50 m (37 ft 9 in)

- Height: 3.74 m (12 ft 3 in)

- Wing area: 23.6 m² (254 ft²)

- Empty weight: 2,440 kg (5,379 lb)

- Loaded weight: 4,250 kg (9,370 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Aichi Atsuta AE1P 32 liquid-cooled inverted V12 piston engine, 1,400 hp (1,044 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 550 km/h (342 mph)

- Range: 1,465 km (910 mi)

- Service ceiling: 10,700 m (35,105 ft)

- Rate of climb: 14 m/s (2,700 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 180 kg/m² (37 lb/ft²)

- Power/mass: 0.25 kW/kg (0.15 hp/lb)

Armament

- 2× forward-firing 7.7 mm Type 97 aircraft machine guns

- 1× rearward-firing 7.92 mm Type 1 machine gun

- 500 kg (1,102 lb) of bombs (design), 800 kg (1,764 lb) of bombs (kamikaze)

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Aichi D3A

- Blackburn Skua

- Breda Ba.65

- Curtiss SB2C Helldiver

- Douglas SBD Dauntless

- Fairey Barracuda

- Heinkel He 118

- Junkers Ju 87

- Vultee Vengeance

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Huggins 2002, p. 67.

- 1 2 Huggins 2002, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Huggins 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ Angelucci 1981, p. 295.

- ↑ Francillion 1970, p. 461.

- ↑ Huggins 2002, p. 69.

- ↑ Huggins 2002, p. 70.

- 1 2 Donald 1997, p. 923.

- ↑ Ishiguro 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ The Maru Mechanic 1981, p. 67.

- ↑ Famous Airplanes of the World 1998, pp. 34–40.

- ↑ Model Art 1993, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR)

- ↑ The Maru Mechanic 1981, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Famous Airplanes of the World 1998, pp. 18–33.

- ↑ The Maru Mechanic 1979, p. 32.

- ↑ O'Neill, Richard (1981). Suicide Squads: Axis and Allied Special Attack Weapons of World War II: their Development and their Missions. London: Salamander Books. p. 296. ISBN 0 861 01098 1.

- ↑ "Video: Planes of Fame D4Y Judy's first engine test". World Warbird News=. Jan 21, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

Bibliography

- Angelucci, Enzo, ed. World Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft. London: Jane's, 1981. ISBN 0-7106-0148-4.

- Donald, David, ed. The Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. London: Aerospace, 1997. ISBN 1-85605-375-X.

- Francillon, René J. Japanese Bombers of World War Two, Volume One. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Hylton Lacy Publishers Ltd., 1969. ISBN 0-85064-022-9.

- Francillon, René J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1979, First edition 1970. ISBN 0-370-30251-6.

- Gunston, Bill. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Combat Aircraft of World War II. London: Salamander Books Ltd., 1978. ISBN 0-89673-000-X

- Huggins, Mark. "Falling Comet: Yokosuka's Suisei Dive-Bomber". Air Enthusiast, No. 97, January/February 2002, pp. 66–71. ISSN 0143-5450.

- "Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR)." National Archives of Japan

- Reference code: C08011073400, Aircraft, weapons and bombs list Himeji Naval Air Base

- Reference code: C08011083500, Kyushu Flying Corps (1st Kokubu)

- Reference code: C08011088800, Delivery articles list Osaka Naval Guard Station Office Oi Base, Tokai Naval Flying Corps (1)

- Reference code: C08011214400, Yamato air base (2)

- Famous Airplanes Of The World No. 69: Navy Carrier Dive-Bomber "Suisei", Bunrindō (Japan), March 1988. ISBN 4-89319-066-0.

- Ishiguro, Ryusuke. Japanese Special Attack Aircraft and Flying Bombs. Tokyo: MMP 2009.

ISBN 978-8-38945-012-8.

- The Maru Mechanic, Ushio Shobō (Japan)

- No. 15 Nakajima C6N1 Carrier Based Rec. Saiun, March 1979

- No. 27 Naval Aero-Technical Arsenal, Carrier Dive Bomber "Suisei D4Y", March 1981

- Model Art, Model Art Co. Ltd. (Japan)

- No. 406, Special issue Camouflage & Markings of Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers in W.W.II, April 1993.

- No. 595, Special issue Night fighters of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, October 2001.

- Richards, M.C. and Donald S. Smith. "Aichi D3A ('Val') & Yokosuka D4Y ('Judy') Carrier Bombers of the IJNAF". Aircraft in Profile, Volume 13. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1974, pp. 145–169. ISBN 0-85383-022-3.

- Vaccari, Pierfrancesco. "La campagna di Iwo Jima e Okinawa" (In Italian). RID magazine, n.1/2002

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yokosuka D4Y. |