Anisakis

| Anisakis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Anisakis simplex | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Secernentea |

| Order: | Ascaridida |

| Family: | Anisakidae |

| Genus: | Anisakis Dujardin, 1845 |

| Species | |

| |

Anisakis is a genus of parasitic nematodes, which have life cycles involving fish and marine mammals.[1] They are infective to humans and cause anisakiasis. People who produce immunoglobulin E in response to this parasite may subsequently have an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis, after eating fish that have been infected with Anisakis species.

Etymology

The genus Anisakis was created in 1845[2] by Félix Dujardin as a subgenus of the genus Ascaris Linnaeus, 1758. Dujardin did not make explicit the etymology but stated that the subgenus included the species in which the males have unequal spicules ("mâles ayant des spicules inégaux"); thus the name Anisakis is based on anis- (Greek prefix for different) and akis (Greek for spine or spicule). Two species were included in the new subgenus, Ascaris (Anisakis) distans Rudolphi, 1809 and Ascaris (Anisakis) simplex Rudolphi, 1809.

Life cycle

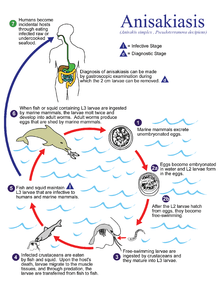

Anisakis species have complex life cycles which pass through a number of hosts through the course of their lives. Eggs hatch in seawater, and larvae are eaten by crustaceans, usually euphausids. The infected crustacean is subsequently eaten by a fish or squid, and the nematode burrows into the wall of the gut and encysts in a protective coat, usually on the outside of the visceral organs, but occasionally in the muscle or beneath the skin. The life cycle is completed when an infected fish is eaten by a marine mammal, such as a whale, seal, or dolphin. The nematode excysts in the intestine, feeds, grows, mates and releases eggs into the seawater in the host's feces. As the gut of a marine mammal is functionally very similar to that of a human, Anisakis species are able to infect humans who eat raw or undercooked fish.

The known diversity of the genus has increased greatly over the past 20 years, with the advent of modern genetic techniques in species identification.[3] Each final host species was discovered to have its own biochemically and genetically identifiable "sibling species" of Anisakis, which is reproductively isolated. This finding has allowed the proportion of different sibling species in a fish to be used as an indicator of population identity in fish stocks.

Morphology

Anisakids share the common features of all nematodes; the vermiform body plan, round in cross section and a lack of segmentation. The body cavity is reduced to a narrow pseudocoel. The mouth is located anteriorly, and surrounded by projections used in feeding and sensation, with the anus slightly offset from the posterior. The squamous epithelium secretes a layered cuticle to protect the body from digestive juices.

As with all parasites with a complex life cycle involving a number of hosts, details of the morphology vary depending on the host and life cycle stage. In the stage which infects fish, Anisakis species are found in a distinctive "watch-spring coil" shape. They are roughly 2 cm long when uncoiled. When in the final host, anisakids are longer, thicker and more sturdy, to deal with the hazardous environment of a mammalian gut.

Health implications

Anisakids pose a risk to human health through intestinal infection with worms from the eating of underprocessed fish, and through allergic reactions to chemicals left by the worms in fish flesh.[4]

Anisakiasis

| Anisakis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | B81.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 127.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 32147 |

| Patient UK | Anisakis |

| MeSH | D017129 |

Anisakiasis is a human parasitic infection of the gastrointestinal tract caused by the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood containing larvae of the nematode Anisakis simplex. The first case of human infection by a member of the family Anisakidae was reported in the Netherlands by Van Thiel, who described the presence of a marine nematode in a patient suffering from acute abdominal pain.[10] It is frequently reported in areas of the world where fish is consumed raw, lightly pickled or salted. The areas of highest prevalence are Scandinavia (from cod livers), Japan (after eating sushi and sashimi), the Netherlands (by eating infected fermented herrings (maatjes)), and along the Pacific coast of South America (from eating ceviche). Fewer than ten cases occur annually in the United States.[11] Development of better diagnostic tools and greater awareness has led to more frequent reporting of anisakiasis.

Within a few hours of ingestion, the parasitic worm tries to burrow though the intestinal wall, but since it cannot penetrate it, it gets stuck and dies. The presence of the parasite triggers an immune response; immune cells surround the worms, forming a ball-like structure that can block the digestive system, causing severe abdominal pain, malnutrition and vomiting. Occasionally, the larvae are regurgitated. If the larvae pass into the bowel or large intestine, a severe eosinophilic granulomatous response may also occur one to two weeks following infection, causing symptoms mimicking Crohn's disease.

Diagnosis can be made by gastroscopic examination, during which the 2-cm larvae are visually observed and removed, or by histopathologic examination of tissue removed at biopsy or during surgery.

Raising consumer and producer awareness about the existence of anisakid worms in fish is a critical and effective prevention strategy. Anisakiasis can be easily prevented by adequate cooking at temperatures greater than 60°C or freezing. The FDA recommends all shellfish and fish intended for raw consumption be blast frozen to −35°C or below for 15 hours or be regularly frozen to −20°C or below for seven days.[11] Salting and marinating will not necessarily kill the parasites. Humans are thought to be more at risk of anisakiasis from eating wild fish rather than farmed fish. Many countries require all types of fish with potential risk intended for raw consumption to be previously frozen to kill parasites. The mandate to freeze herring in the Netherlands has virtually eliminated human anisakiasis.[12]

Allergic reactions

Even when the fish is thoroughly cooked, Anisakis larvae pose a health risk to humans. Anisakids (and related species such as the sealworm, Pseudoterranova species, and the codworm Hysterothylacium aduncum) release a number of biochemicals into the surrounding tissues when they infect a fish. They are also often consumed whole, accidentally, inside a fillet of fish.

Acute allergic manifestations, such as urticaria and anaphylaxis, may occur with or without accompanying gastrointestinal symptoms. The frequency of allergic symptoms in connection with fish ingestion has led to the concept of gastroallergic anisakiasis, an acute IgE-mediated generalized reaction.[10] Occupational allergy, including asthma, conjunctivitis, and contact dermatitis, has been observed in fish processing workers.[13] Sensitivization and allergy are determined by skin-prick test and detection of specific antibodies against Anisakis. Hypersensitivity is indicated by a rapid rise in levels of IgE in the first several days following consumption of infected fish.[10]

Treatment

For the worm, humans are a dead-end host. Anisakis and Pseudoterranova larvae cannot survive in humans, and will eventually die. In some cases, the infection will resolve with only symptomatic treatment.[14] In other cases, however, infection can lead to small bowel obstruction, which may require surgery,[15] although treatment with albendazole alone (avoiding surgery) has been reported to be successful. Intestinal perforation (an emergency) is also possible.[16]

Occurrence

Larval anisakids are common parasites of marine and anadromous fish (e.g. salmon, sardine), and can also be found in squid and cuttlefish. In contrast, they are absent from fish in waters of low salinity, due to the physiological requirements of euphausiids, which are needed to complete their life cycle. Anisakids are also uncommon in areas where cetaceans are rare, such as the southern North Sea.[17]

Similar parasites

- Cod or seal worm Pseudoterranova (Phocanema, Terranova) decipiens

- Contracaecum spp.

- Hysterothylacium (Thynnascaris) spp.

See also

References

- ↑ Berger SA, Marr JS. Human Parasitic Diseases Sourcebook. Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, Massachusetts, 2006.

- ↑ Dujardin F. 1845. Histoire naturelle des helminthes ou vers intestinaux. xvi, 654+15 pp. (Anisakis: page 220)

- ↑ Mattiucci, S.; Nascetti, G. (2006). "Molecular systematics, phylogeny and ecology of anisakid nematodes of the genus Anisakis Dujardin, 1845: an update". Parasite. 13 (2): 99–113. doi:10.1051/parasite/2006132099. ISSN 1252-607X. PMID 16800118.

- ↑ Amato Neto V, Amato JG, Amato VS (2007). "Probable recognition of human anisakiasis in Brazil". Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 49 (4): 261–2. doi:10.1590/s0036-46652007000400013. PMID 17823758.

- ↑ WaiSays: About Consuming Raw Fish Retrieved on April 14, 2009

- ↑ For Chlonorchiasis: Public Health Agency of Canada > Clonorchis sinensis - Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) Retrieved on April 14, 2009

- ↑ For Anisakiasis: WrongDiagnosis: Symptoms of Anisakiasis Retrieved on April 14, 2009

- ↑ For Diphyllobothrium: MedlinePlus > Diphyllobothriasis Updated by: Arnold L. Lentnek, MD. Retrieved on April 14, 2009

- ↑ For symptoms of diphyllobothrium due to vitamin B12-deficiency University of Maryland Medical Center > Megaloblastic (Pernicious) Anemia Retrieved on April 14, 2009

- 1 2 3 Audicana, Maria Teresa; Kennedy, MW (2008). "Anisakis Simplex: From Obscure Infectious Worm to Inducer of Immune Hypersensitivity". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (2): 360–379. doi:10.1128/CMR.00012-07. PMC 2292572

. PMID 18400801.

. PMID 18400801. - 1 2 Bad Bug Book: Foodborne Pathogens Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook. Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ John, David T.; William Petri (2006). Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. St. Louis: Saunders. pp. 267–270. ISBN 0-7216-7634-0.

- ↑ Nieuwenhuizen, N; Lopata, AL; Jeebhay, MF; Herbert, DR; Robins, TG; Brombacher, F (2003). "Exposure to the Fish Parasite Anisakis Causes Allergic Airway Hyperreactivity and Dermatitis". The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 117 (5): 1098–105. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1357. PMID 16675338.

- ↑ Nakaji K (2009). "Enteric anisakiasis which improved with conservative treatment". Intern. Med. 48 (7): 573. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1905. PMID 19336962.

- ↑ Sugita S, Sasaki A, Shiraishi N, Kitano S (April 2008). "Laparoscopic treatment for a case of ileal anisakiasis". Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 18 (2): 216–8. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e318166145c. PMID 18427347.

- ↑ Pacios, Enrique; Arias‐diaz, Javier; Zuloaga, Jaime; Gonzalez‐armengol, Juan; Villarroel, Pedro; Balibrea, Jose L. (2005). "Albendazole for the Treatment of Anisakiasis Ileus". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (12): 1825–6. doi:10.1086/498309. PMID 16288416.

- ↑ Grabda, J. (1976). "Studies on the life cycle and morphogenesis of Anisakis simplex (Rudolphi, 1809)(Nematoda: Anisakidae) cultured in vitro". Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria. 6 (1): 119–131. doi:10.3750/aip1976.06.1.08.